dress

body covering

Introduction

also called apparel or attire

clothing and accessories for the human body. The variety of dress is immense. The style that a particular individual selects is often linked to his sex, age, socioeconomic status, culture, geographic area, and historical era.

clothing and accessories for the human body. The variety of dress is immense. The style that a particular individual selects is often linked to his sex, age, socioeconomic status, culture, geographic area, and historical era.This article considers the chronological development of fashionable dress and decoration—that is, the attire selected and adopted by the leading members of a society. This reflects the fact that in any group of people—whether constituting a small community or a great nation—it is usually those with wealth and power who influence, and even dictate, fashions to other members. The discussion does not concentrate solely on apparel but also covers, as appropriate, certain aspects of hairdressing, jewelry, and the use of cosmetics (cosmetic). In addition, the nature and purposes of dress and some of the specific social, political, economic, geographic, and technological factors influencing changes in fashion are treated. Not treated here are specialized attire, including ecclesiastical dress; military dress; academic, trade, or professional dress; and the national or regional costumes of peasant or indigenous peoples.

The history of Middle (Middle East, ancient) Eastern and Western dress

Ancient Egypt (Egypt, ancient)

Modern knowledge of ancient Egyptian (Egypt, ancient) dress derives from the ample evidence to be seen in the wealth of wall and sarcophagus paintings, in sculpture, and in ceramics; few actual garments have survived. Such illustrative material is depicted clearly and colourfully, but care must be taken in interpreting the designs too literally, partly because the art is frequently stylized but also because the artists were bound by tradition and their representation of dress often lagged far behind the actual changes of fashion.

The chief textile to have been preserved is linen, which has been found in graves from the Neolithic Period. The growing of flax, from which linen is made, dates from very early times; the Egyptians believed that the gods were clothed in linen before they came to earth. wool was more rarely employed, and sericulture, the raising of silkworms, had not yet extended as far west as Egypt.

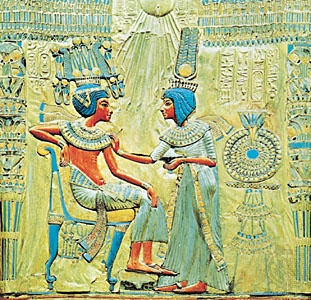

The technique of using mordants (mordant dye), any of several chemicals used to bind dyes (dye) to cloth, was slow to come to Egypt, so most garments were white. Instead, colour was provided by jewelry, in which semiprecious stones were widely incorporated. Among the most common types, the characteristic deep, decorative collar, worn by both sexes, was introduced early. These brightly hued bands were made of embroidered (embroidery) and beaded (beadwork) materials and set around the neck and shoulders either on bare skin or on top of a white cape or gown. In some depictions the collar is clearly the major, if not the only, item of apparel worn.

The technique of using mordants (mordant dye), any of several chemicals used to bind dyes (dye) to cloth, was slow to come to Egypt, so most garments were white. Instead, colour was provided by jewelry, in which semiprecious stones were widely incorporated. Among the most common types, the characteristic deep, decorative collar, worn by both sexes, was introduced early. These brightly hued bands were made of embroidered (embroidery) and beaded (beadwork) materials and set around the neck and shoulders either on bare skin or on top of a white cape or gown. In some depictions the collar is clearly the major, if not the only, item of apparel worn.During the most distant era, dress for both sexes was confined to loincloths (loincloth), a vest or shirt, capes, and robes. Skins of various animals were utilized. These were sometimes simply raw hides (hide), which have survived only rarely, but the Egyptians became skilled at curing the skins to become leather by the tawing method—that is, by the use of alum or salt. Tawing yields a white, stiff leather that may be dyed (dye) various colours (colour). Later they adopted the tanning method, employing oak galls for the purpose. Leather was used widely in dress for footwear, belts, and straps.

During the 3,000 years of the ancient Egyptian culture, costume changed comparatively little and very slowly. It generally emphasized a draped style of dress, the garments consisting of pieces of material held in place around the body by knots tied in the fabric and by belts, sashes, and collars. Little sewing was needed, being confined generally to side seams and, in later years, to armholes. This draped type of dress conformed to that of other civilizations in the Mediterranean and Middle Eastern region, such as Greece, Rome, and Mesopotamia, but differed from the styles of Persia, northern India, and China, where people wore more fitted, sewn garments based upon coats, tunics (tunic), and trousers.

Over the years the style of these garments slowly evolved and became more complex; a greater number were worn either in combination with or on top of one another. During the Old Kingdom (Egypt, ancient) (its capital at Memphis), which lasted until about 2130 BCE, dress was simple. Men wore a short skirt tied at the waist or held there by a belt. As time passed, the skirt became pleated or gathered. Important people wore in addition a decorative coloured pendant hanging in front from the waist belt and a shoulder cape or corselet partly covering their bare torso. A sheathlike gown was typical of feminine attire. This encased the body from the ankles to just below the breasts and was held up by decorative shoulder straps. Woolen (wool) cloaks were worn for warmth by men and women.

Over the years the style of these garments slowly evolved and became more complex; a greater number were worn either in combination with or on top of one another. During the Old Kingdom (Egypt, ancient) (its capital at Memphis), which lasted until about 2130 BCE, dress was simple. Men wore a short skirt tied at the waist or held there by a belt. As time passed, the skirt became pleated or gathered. Important people wore in addition a decorative coloured pendant hanging in front from the waist belt and a shoulder cape or corselet partly covering their bare torso. A sheathlike gown was typical of feminine attire. This encased the body from the ankles to just below the breasts and was held up by decorative shoulder straps. Woolen (wool) cloaks were worn for warmth by men and women. Under the Middle Kingdom (Egypt, ancient) (its capital at Thebes), which prospered until about 1630 BCE, the masculine skirt could be hip- or ankle-length. More material was now used, making the garment fuller, such fullness being concentrated in the centre front; and the pendants became more elaborate and ornamental. A cape might be draped around the shoulders and knotted on the chest. Late in the period a double skirt was introduced; alternatively, a triangular loincloth might be worn under a skirt.

Under the Middle Kingdom (Egypt, ancient) (its capital at Thebes), which prospered until about 1630 BCE, the masculine skirt could be hip- or ankle-length. More material was now used, making the garment fuller, such fullness being concentrated in the centre front; and the pendants became more elaborate and ornamental. A cape might be draped around the shoulders and knotted on the chest. Late in the period a double skirt was introduced; alternatively, a triangular loincloth might be worn under a skirt.The most elaborate dress for both sexes was to be seen under the New Kingdom (Egypt, ancient) from about 1539 BCE until the Egyptians were conquered by the Assyrians (671 BCE), the Persians (525 BCE), Alexander the Great (332 BCE), and finally Rome (30 BCE). During these later years Egyptian dress was strongly influenced by that of the conquerors. New Kingdom dress was more complex than theretofore. The garments were of similar type but were composed of larger pieces of material; draping became more complicated and ornamentation richer. A robe or gown was now worn by important persons of both sexes. It consisted of a piece of fabric measuring 5 by 4 feet (1.5 by 1.2 metres) that was draped and held in place by pins and a waist belt, creating wide, elbow-length sleeves. There were many ways of draping the material, but with most methods all the pleats and folds seemed to be gathered around a single point at the waist. The cape, decorative collar, skirt, and pendant girdle also continued to be worn. Foci of bright colour were provided by the deep collar and pendant apron. Embroidered and carved ornamental motifs included especially the lotus flower, the papyrus bundle, birds in flight, and many geometric forms. Sacred emblems such as the scarab beetle and the asp were worn by priests and royalty.

Children (childhood) were dressed, as in most of the history of costume everywhere, as miniature versions of their parents, although they are often depicted wearing little at all—not surprising considering the climate of Egypt. Servants also were almost naked, as were labourers in the fields, who are depicted clad only in a loincloth.

Heavy wigs (wig) or a padding of false hair (hairdressing), worn by men and women alike, are known from an early period. They served not only as an adornment but also to protect the wearer's head from the burning rays of the Sun, thus in a way acting as hats (hat). Semicircular kerchiefs, tied by the corners at the nape of the neck under the hair, were sometimes worn to protect the wig on a dusty day. Wigs were dressed in many different ways, each characteristic of a given period; generally speaking, the hair became longer and the arrangement of curls and braids—set with beeswax—more complicated as time went on.

The earliest records indicate that Egyptian men grew hair on their chins. They might frizz, dye, or use henna on this beard, and sometimes they plaited it with interwoven gold thread. Later, a metal false beard, or postiche, which was a sign of sovereignty, was worn by royalty. This was held in place by a ribbon tied over the head and attached to a gold chin strap, a fashion existing from about 3000 to 1580 BCE.

Many people went barefoot, especially indoors, but people of rank are depicted outdoors in sandals (sandal) made from palm leaves, papyrus, or leather.

Cosmetics (cosmetic) were extensively applied by both sexes, and considerable knowledge of their use is available because of the Egyptian custom of burying comforts and luxuries with the dead. Examples of the cosmetics used and of the means of making, applying, and keeping them may be seen in museums, especially in Cairo and London. The Egyptians applied rouge to their cheeks, red ointment to their lips, and henna to their nails and feet, and ladies traced the veins on their temples and breasts with blue paint, tipping their nipples with gold. The chief focus of makeup was the eye, where a green eye shadow (made from powdered malachite) and a black or gray eyeliner was applied; the latter substance, called kohl, was manufactured from, among other materials, powdered antimony, carbon, and oxide of copper.

Mesopotamia (Mesopotamia, history of)

Ancient Mesopotamia (Mesopotamia, history of) was situated in the area of land that is defined by the great Tigris and Euphrates river system (Tigris-Euphrates river system) and that is contained within modern Iraq. Several important cultures arose there, their empires waxing and waning successively as well as overlapping in time. Among the most prominent were the empires of Sumeria (Sumer), Akkad, Assyria, and Babylonia.

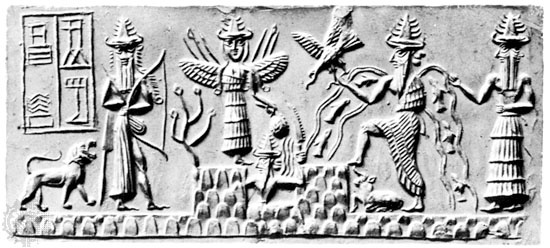

Ancient Mesopotamia (Mesopotamia, history of) was situated in the area of land that is defined by the great Tigris and Euphrates river system (Tigris-Euphrates river system) and that is contained within modern Iraq. Several important cultures arose there, their empires waxing and waning successively as well as overlapping in time. Among the most prominent were the empires of Sumeria (Sumer), Akkad, Assyria, and Babylonia. The Sumerian civilization was established before 4000 BCE and reached a high level of culture between 2700 and 2350 BCE. In early times both sexes wore sheepskin skirts with the skin turned inside and the wool combed into decorative tufts. These wraparound skirts were pinned in place and extended from the waist to the knees or, for more important persons, to the ankles. The upper part of the torso was bare or clothed by another sheepskin cloaking the shoulders. From about 2500 BCE a woven woolen fabric replaced the sheepskin, but the tufted effect was retained, either by sewing tufts onto the garment or by weaving loops into the fabric. Named kaunakes by the Greeks, this tufted fabric is shown in all the sculptures and mosaics of the period, as, for example, in the art from the excavations at Ur exhibited in the British Museum in London. At this time, also, long cloaks were worn, and materials for garments and head coverings included felted wool and leather.

The Sumerian civilization was established before 4000 BCE and reached a high level of culture between 2700 and 2350 BCE. In early times both sexes wore sheepskin skirts with the skin turned inside and the wool combed into decorative tufts. These wraparound skirts were pinned in place and extended from the waist to the knees or, for more important persons, to the ankles. The upper part of the torso was bare or clothed by another sheepskin cloaking the shoulders. From about 2500 BCE a woven woolen fabric replaced the sheepskin, but the tufted effect was retained, either by sewing tufts onto the garment or by weaving loops into the fabric. Named kaunakes by the Greeks, this tufted fabric is shown in all the sculptures and mosaics of the period, as, for example, in the art from the excavations at Ur exhibited in the British Museum in London. At this time, also, long cloaks were worn, and materials for garments and head coverings included felted wool and leather. Both sexes seem to have often worn large wigs, as in ancient Egypt. Metalworking was of a high standard, as may be seen in the elaborate golden jewelry, which was encrusted with semiprecious stones and worn by both sexes. Brooches (brooch), earrings (earring), hair ornaments, and neck chains have all been found.

Both sexes seem to have often worn large wigs, as in ancient Egypt. Metalworking was of a high standard, as may be seen in the elaborate golden jewelry, which was encrusted with semiprecious stones and worn by both sexes. Brooches (brooch), earrings (earring), hair ornaments, and neck chains have all been found.A different style of dress is evident in Mesopotamian sculptures dating after about 2370 BCE. Both men and women were clothed in a large piece of material—most commonly of wool, though later also of linen—draped around the body over a skirt. This garment, similar to a shawl, was characteristically edged with tassels or fringe. The draping varied, but, for men at least, the fabric was arranged so that the fullness was at the rear, leaving the right, or sword, arm free. This newer form of dress had originated from farther north and east and was adopted by the Semitic people of Akkad under Sargon (the dynasty founded by Sargon lasted from c. 2334 to c. 2193 BCE) and by the revitalized Sumerian culture in the years 2110–2010 BCE.

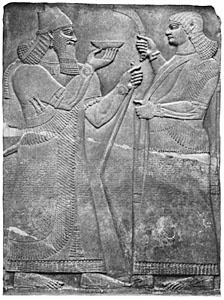

The dress worn in Mesopotamia by the Babylonians (Babylonia) (2105–1240 BCE) and the Assyrians (Assyria) (1200–540 BCE) evolved into a more sophisticated version of Sumerian and Akkadian styles. Ample evidence of this more elaborate draped costume can be seen in the large relief sculptures of the age. There were two basic garments for both sexes: the tunic and the shawl, each cut from one piece of material. The knee- or ankle-length tunic had short sleeves and a round neckline. Over it were draped one or more shawls of differing proportions and sizes but all generally fringed or tasseled. Broad belts held the shawls in position. Wool was the most frequently used material, in bright or strong colours. Decoration was rich, in allover patterns or in borders, carried out in embroidery or by printing. Motifs were chiefly geometric. Women wore a short skirt as underwear, men a loincloth. Footwear for both sexes was made from fabric or soft leather in the form of sandals or boots.

The dress worn in Mesopotamia by the Babylonians (Babylonia) (2105–1240 BCE) and the Assyrians (Assyria) (1200–540 BCE) evolved into a more sophisticated version of Sumerian and Akkadian styles. Ample evidence of this more elaborate draped costume can be seen in the large relief sculptures of the age. There were two basic garments for both sexes: the tunic and the shawl, each cut from one piece of material. The knee- or ankle-length tunic had short sleeves and a round neckline. Over it were draped one or more shawls of differing proportions and sizes but all generally fringed or tasseled. Broad belts held the shawls in position. Wool was the most frequently used material, in bright or strong colours. Decoration was rich, in allover patterns or in borders, carried out in embroidery or by printing. Motifs were chiefly geometric. Women wore a short skirt as underwear, men a loincloth. Footwear for both sexes was made from fabric or soft leather in the form of sandals or boots. Care of the coiffure was very important for men and women among both the Assyrians and the Babylonians. The hair was grown long and carefully curled and ringleted, with false hair added if needed. Perfumes (perfume), oils, and black dye were used on the hair. Men grew long, carefully tended curled beards. A band of metal or fabric encircled the brow, or a woolen, felt, or leather cap shaped like a fez was worn. The royal headdress resembled a pleated crown or a mitre and had dependent lappets at the rear. Jeweled ornamentation to the costume was rich and heavy and of high quality.

Care of the coiffure was very important for men and women among both the Assyrians and the Babylonians. The hair was grown long and carefully curled and ringleted, with false hair added if needed. Perfumes (perfume), oils, and black dye were used on the hair. Men grew long, carefully tended curled beards. A band of metal or fabric encircled the brow, or a woolen, felt, or leather cap shaped like a fez was worn. The royal headdress resembled a pleated crown or a mitre and had dependent lappets at the rear. Jeweled ornamentation to the costume was rich and heavy and of high quality.The Aegean (Aegean civilizations): Minoan (Minoan civilization) and Mycenaean dress

The Aegean region—and in particular the island of Crete, which was inhabited from about 6000 BCE—can be considered the cradle of western European culture. Settlers came to Crete from areas farther east, including Anatolia, North Africa, Syria, and Palestine. By 2500 BCE the Cretan civilization was becoming established. As a maritime people with extensive trade in the Mediterranean and the Middle East, the Cretans were influenced by many sources. They created a society and a dress style of their own, one dissimilar from the earlier styles of Egypt and the later styles of Greece.

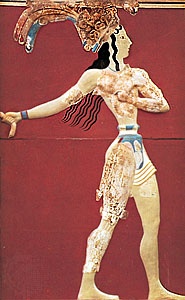

The Aegean region—and in particular the island of Crete, which was inhabited from about 6000 BCE—can be considered the cradle of western European culture. Settlers came to Crete from areas farther east, including Anatolia, North Africa, Syria, and Palestine. By 2500 BCE the Cretan civilization was becoming established. As a maritime people with extensive trade in the Mediterranean and the Middle East, the Cretans were influenced by many sources. They created a society and a dress style of their own, one dissimilar from the earlier styles of Egypt and the later styles of Greece.The greatest and most prosperous years were from 1750 to 1400 BCE; this was the time of the building of the great palaces, notably the complex at Knossos, from where the remains of coloured frescoes (fresco painting), painted vases, and sculpture in marble, terra-cotta, and coloured ceramics have been excavated. Even finer and more complete frescoes have been preserved from the excavations of the Minoan (Minoan civilization) city on the island of Thera (Thíra), an island largely destroyed in the cataclysmic volcanic eruption of about 1500 BCE.

Cretan dress is characterized by its vivid colouring, elegance, and sophistication. It is also notable for the gaiety of feminine attire, typical of a society where women—unlike in Classical Greece—are depicted side-by-side with men, apparently taking part in all the activities of life and not relegated to the domestic background. Men's garments were few. Chief of these was a loincloth of wool, leather, or linen, tightly belted at the waist and arranged as a short, elaborately decorated skirt. The belt was drawn tight to accentuate the slender waist. By 1750 BCE women were wearing a long bell-shaped skirt, often in a series of flounces, over a loincloth; with this, they wore a bolero-like jacket that had elbow-length sleeves but was open in front, leaving the breasts bare. In the later period a bodice was worn, constricting the upper torso but accentuating the full, bare breasts above. Such clothing may have been associated with priestesses or goddesses rather than ordinary women, however.

The Cretans liked bright colours, and their dress was vividly embroidered and decorated. The hair of both sexes was worn long, looped and braided and dressed with jewels, pearls (pearl), and ribbons. The Cretans bathed frequently, oiling their bodies afterward. Men were generally clean-shaven. Outdoors both sexes wore sandals or shoes (shoe). In winter calf-length boots were adopted, and short woolen, fur-lined cloaks were fastened by pins around the shoulders.

With the collapse of the Minoan civilization in Crete about 1400 BCE, a new culture arose on the mainland in the Peloponnese, notably in the maritime principalities of Mycenae, Tiryns, and Pylos. As the frescoes from the palace of Tiryns illustrate, the costume was similar but richer still.

Ancient Greece (ancient Greek civilization)

ancient Greek civilization is customarily classified into three segments. Up to about 500 BCE is described as the Archaic period. This was the time when the several different civilizations of mainland and island Greece, Anatolia, and North Africa coexisted, the arts and costume of each influencing the others. The Dorians (Dorian) had invaded the Minoan kingdoms in Crete and the Peloponnese from about 1200 BCE. They were a northern race from Illyria and a less technologically developed society than the Minoans. Modern knowledge of their dress is imperfect, but it seems to have been simple. Woolen cloth, made from the flocks of local sheep, was employed. It was cut into squares of fabric and then pinned on the shoulders and bound around the body. The influence from Anatolia, where the inland climate was more severe, introduced hooded cloaks, banded leg coverings, and Phrygian caps (Phrygian cap) with a point on top.

ancient Greek civilization is customarily classified into three segments. Up to about 500 BCE is described as the Archaic period. This was the time when the several different civilizations of mainland and island Greece, Anatolia, and North Africa coexisted, the arts and costume of each influencing the others. The Dorians (Dorian) had invaded the Minoan kingdoms in Crete and the Peloponnese from about 1200 BCE. They were a northern race from Illyria and a less technologically developed society than the Minoans. Modern knowledge of their dress is imperfect, but it seems to have been simple. Woolen cloth, made from the flocks of local sheep, was employed. It was cut into squares of fabric and then pinned on the shoulders and bound around the body. The influence from Anatolia, where the inland climate was more severe, introduced hooded cloaks, banded leg coverings, and Phrygian caps (Phrygian cap) with a point on top.A later Archaic culture, the Ionian, then established itself in Greece. The Ionians developed a higher-quality textile industry, producing finer materials in wool and linen that were more suited to a draped style of dress. In the 8th and 7th centuries BCE the Ionians developed an extensive trading economy around the Mediterranean region from Gaul in the west to Libya in the east.

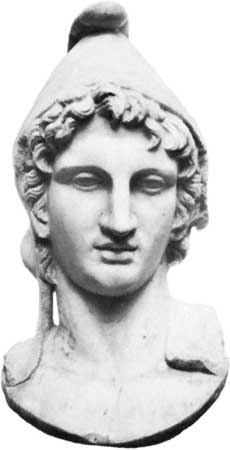

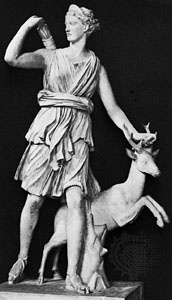

The 5th and 4th centuries BCE were the years of the great Classical period, the time when a very simple but highly sophisticated and superb quality of work was achieved. Greek literature, architecture (Western architecture), and sculpture (Western sculpture) were particularly fine. This was the case with costume as well, the designs of which can be studied in detail from painted vases (Greek pottery) and sculpture. Classical Greek dress was a draped style, one in which there was little sewing. The garments for men and women were similar, consisting of oblong pieces of fabric in different sizes and materials, draped in various ways and held in place by ribbons and decorative pins. The dress was a totally natural one; there was no constriction and no padding. The simplicity of the dress was offset by the myriad ways of wearing it, a sophistication achieved by personal expression of the wearer.

The 5th and 4th centuries BCE were the years of the great Classical period, the time when a very simple but highly sophisticated and superb quality of work was achieved. Greek literature, architecture (Western architecture), and sculpture (Western sculpture) were particularly fine. This was the case with costume as well, the designs of which can be studied in detail from painted vases (Greek pottery) and sculpture. Classical Greek dress was a draped style, one in which there was little sewing. The garments for men and women were similar, consisting of oblong pieces of fabric in different sizes and materials, draped in various ways and held in place by ribbons and decorative pins. The dress was a totally natural one; there was no constriction and no padding. The simplicity of the dress was offset by the myriad ways of wearing it, a sophistication achieved by personal expression of the wearer.As time passed and finer materials (mostly linen) were produced, a further variety in draping was created by pleating, a treatment particularly in use for feminine wear. The pieces of material were set into pleats, soaked in a thin starch solution, twisted and tied at the ends, then left in the sun to dry. This gave a greater permanence to the pleating.

The subject of colour in Greek dress is a difficult one. Neither sculpture nor vases (which are in black, red, and white) provide information. For a long time it was believed that the dress was largely white, and the reintroduction of the “Greek” style in Regency England and Directoire France presumed this from the marble sculpture. It is known, however, that buildings and ornament were painted in bright colours, and literary sources report colour being employed. Decoration was most often by the Classical ornament forms seen in architecture: the fret (key) pattern, flowers such as honeysuckle in running anthemion patterns, circles (paterae), and stripes.

The Hellenistic Age of Greek culture, dating from 323 BCE and lasting until Greece became part of the Roman Empire in 30 BCE, was a wealthier time, reflecting the wider boundaries of the Greek world resulting from the conquests of Alexander the Great. To the fine linens available in costume were added cotton from India and silk from China; thus the draped mode became more varied and elaborate.

From Classical times the chief garment was the chiton, a type of tunic made from one or two pieces of material hanging back and front, pinned on one or both shoulders, and girded. For men the chiton was usually knee-length and seamed up one or both sides. An ankle-length version was worn by women and for more formal wear by men. The simplest type of chiton was sleeveless, but later a sleeved version was made possible by using a much wider piece of material pinned at intervals at shoulder level, creating an elbow-length wide sleeve. A variation on the chiton style for both sexes was achieved by wearing a double girdle, one at waist level and one around the hips, the material being bloused out in between. The peplos was an additional garment worn by women. Made of one or two pieces of fabric, it hung from the shoulder pins to above or below the waist girdle. Alternatively, women used a longer piece of the chiton material and folded it over in front to hang in a similar manner.

From Classical times the chief garment was the chiton, a type of tunic made from one or two pieces of material hanging back and front, pinned on one or both shoulders, and girded. For men the chiton was usually knee-length and seamed up one or both sides. An ankle-length version was worn by women and for more formal wear by men. The simplest type of chiton was sleeveless, but later a sleeved version was made possible by using a much wider piece of material pinned at intervals at shoulder level, creating an elbow-length wide sleeve. A variation on the chiton style for both sexes was achieved by wearing a double girdle, one at waist level and one around the hips, the material being bloused out in between. The peplos was an additional garment worn by women. Made of one or two pieces of fabric, it hung from the shoulder pins to above or below the waist girdle. Alternatively, women used a longer piece of the chiton material and folded it over in front to hang in a similar manner. There were two chief forms of cloak or wrap. The smaller one—the chlamys—was of dark wool and was worn pinned on one shoulder, usually leaving the right arm free. The larger wrap was the himation, worn by both sexes. Draped in many different ways, it covered the body and could be drawn up over the head. In sculpture, philosophers and statesmen are commonly depicted wearing the himation.

There were two chief forms of cloak or wrap. The smaller one—the chlamys—was of dark wool and was worn pinned on one shoulder, usually leaving the right arm free. The larger wrap was the himation, worn by both sexes. Draped in many different ways, it covered the body and could be drawn up over the head. In sculpture, philosophers and statesmen are commonly depicted wearing the himation.Knowledge of underwear is limited. Literary sources tell of a linen girdle and a band to delineate the breasts. Men wore a loincloth.

Men's hair was long in the early years, but later it was cut short and carefully curled. bleach was often used to make the hair fashionably blond; perfumes and pomades were applied. Beards were common until the time of Alexander. Most men were bareheaded, a hat being reserved for bad weather. There was a low-crowned, broad-brimmed style—the petasos—and a brimless cap, the pilos. Women's hair was long; it was usually curled and waved on the forehead and sides and drawn to a chignon at the nape. Many women wore wigs of different shades and decorated their coiffure with flowers, jewels, and fillets. They draped the head with the cloak and, in the Hellenistic period, sometimes perched a straw hat on top.

Men's hair was long in the early years, but later it was cut short and carefully curled. bleach was often used to make the hair fashionably blond; perfumes and pomades were applied. Beards were common until the time of Alexander. Most men were bareheaded, a hat being reserved for bad weather. There was a low-crowned, broad-brimmed style—the petasos—and a brimless cap, the pilos. Women's hair was long; it was usually curled and waved on the forehead and sides and drawn to a chignon at the nape. Many women wore wigs of different shades and decorated their coiffure with flowers, jewels, and fillets. They draped the head with the cloak and, in the Hellenistic period, sometimes perched a straw hat on top.Both sexes went barefoot indoors but outside wore leather sandals. Men also wore boots, which were laced up the front and might be fur-lined.

Greek jewelry was very fine and was, especially in the later centuries, worn in abundance. Both sexes used perfume, and women employed extensive makeup to give brilliance to their eyes, lashes, and cheeks.

Etruria

Cultural development came later to Italy than to the Aegean area. The Greeks colonized southern Italy and Sicily from the later 7th century BCE, but it was the Etruscans (Etruscan) who introduced a high standard of civilization, in the previous century, to the central region of the peninsula. They called themselves the Rasenna, though in Latin they were known as the Etrusci or Tusci. It is believed that they may have emigrated from Anatolia or possibly from farther east. They quickly developed their culture in their new land, and, soon after 700 BCE, they were living in an urban society capable of a high standard of building and visual arts. In dress, as in the other applied arts, they drew their inspiration and knowledge from a mixture of sources, chiefly Greek and Middle Eastern.

Cultural development came later to Italy than to the Aegean area. The Greeks colonized southern Italy and Sicily from the later 7th century BCE, but it was the Etruscans (Etruscan) who introduced a high standard of civilization, in the previous century, to the central region of the peninsula. They called themselves the Rasenna, though in Latin they were known as the Etrusci or Tusci. It is believed that they may have emigrated from Anatolia or possibly from farther east. They quickly developed their culture in their new land, and, soon after 700 BCE, they were living in an urban society capable of a high standard of building and visual arts. In dress, as in the other applied arts, they drew their inspiration and knowledge from a mixture of sources, chiefly Greek and Middle Eastern. The Etruscans also had a close affinity of dress with the Minoans, with sewn and fitted garments, bright colouring, rich decoration, and an abundance of beautiful jewelry, especially in gold. Nevertheless, Etruscan dress, for both sexes, demonstrates a marriage between East and West, blending Eastern features from Egypt, Syria, and Crete with a later Ionian-style draped attire probably derived from the contemporary Greek colonists in southern Italy. Thus, Etruscans can be seen wearing both draped, pinned tunics and fitted, sewn ones, or such Greek styles as the chlamys, himation, or chiton in conjunction with footwear with Middle Eastern-style turned-up toes. Some Etruscan garments presaged later styles; for example, the tebenna, a semicircular mantle, was an early version of the Roman toga, and a decorative collar derived from Egypt anticipated a later Byzantine version.

The Etruscans also had a close affinity of dress with the Minoans, with sewn and fitted garments, bright colouring, rich decoration, and an abundance of beautiful jewelry, especially in gold. Nevertheless, Etruscan dress, for both sexes, demonstrates a marriage between East and West, blending Eastern features from Egypt, Syria, and Crete with a later Ionian-style draped attire probably derived from the contemporary Greek colonists in southern Italy. Thus, Etruscans can be seen wearing both draped, pinned tunics and fitted, sewn ones, or such Greek styles as the chlamys, himation, or chiton in conjunction with footwear with Middle Eastern-style turned-up toes. Some Etruscan garments presaged later styles; for example, the tebenna, a semicircular mantle, was an early version of the Roman toga, and a decorative collar derived from Egypt anticipated a later Byzantine version.Ancient Rome

The civilization of ancient Rome spanned more than a thousand years, from the traditional founding of the walled city in the mid-8th century BCE to the final collapse of the western part of the empire in 476 CE. Until the 3rd century BCE the Romans derived their culture from the Greeks and the Etruscans but after this gradually began to develop their own civilization and to expand their influence, taking over territory after territory—first that of the Etruscans, then Sicily, Carthage and North Africa, Greece, and Egypt. They went on to found the great Roman Empire, which by the 2nd century CE extended from Spain to the Black Sea and from Britain to Egypt.

The history of Roman dress is paralleled by that of Roman arts and architecture (Western architecture). They inherited many ideas from the Greeks, but, as the empire extended its borders and incorporated peoples of different customs, climates, and religions, matters of style became more complex. In costume, as in art, the trend was toward a more ornate, richly coloured, more varied, and, especially in the later days of the empire, very luxurious attire. Roman dress also reflected a distinct division of social class, with certain colours, fabrics, and styles reserved for citizens and important personages.

With the expansion of the empire, wider trading (international trade) was made possible. This increased the availability of more varied and elegant fabrics. Cotton from India and silks from East Asia were accessible to the wealthy, enriched by high-quality embroidered edging and fringing. Elagabalus (218–222 CE) was the first Roman emperor to wear silk. Later, looms (loom) were set up to weave silk, but China retained control of sericulture, exporting only silk thread or fabric, both of which were expensive.

The art of dyeing and knowledge of the use of mordants was now more extensive. The famous dye of the Classical world was Tyrian purple, so called because its centre of production was in the twin cities of Tyre and Sidon (now in Lebanon). The dye was obtained from small glands in the mollusk purpura and was costly owing to the small size of the source material. Thus, the wearing of Tyrian purple was reserved for a few; although the name Purpura gave rise to the word purple, the colour would be described today as something between red and purple. Under the empire, production sites were established in Crete, Sicily, and Anatolia. At Taranto in southern Italy a hill survives that is composed entirely of the shells of the Purpura mollusk.

The garment for which Rome is most famous is the toga. A large piece of material wrapped around the masculine body as a cloak, the toga served a similar function as the Greek himation, although the fabric was of quite a different shape. Under the empire, the toga acquired a special distinction because of its unique and complex method of draping and because, as a note of rank, its wearing was restricted to Roman citizens. The toga was not rectangular in shape like the himation but was a segment of a circle, measuring about 18 feet (5.5 metres) along the chord of the segment and about 5.5 feet (1.7 metres) at its widest point. It was made of wool and so was very heavy. To drape it, about five feet of the straight edge of the fabric was placed against the centre front of the body from ground level upward. The rest of the material was then thrown over the left shoulder and passed around the back, under the right arm, and once again over the left shoulder and arm. The right arm was therefore left free. The material could be pouched in front as well as drawn up over the head. Certain patterns and colours were worn by specific members of society.

The garment for which Rome is most famous is the toga. A large piece of material wrapped around the masculine body as a cloak, the toga served a similar function as the Greek himation, although the fabric was of quite a different shape. Under the empire, the toga acquired a special distinction because of its unique and complex method of draping and because, as a note of rank, its wearing was restricted to Roman citizens. The toga was not rectangular in shape like the himation but was a segment of a circle, measuring about 18 feet (5.5 metres) along the chord of the segment and about 5.5 feet (1.7 metres) at its widest point. It was made of wool and so was very heavy. To drape it, about five feet of the straight edge of the fabric was placed against the centre front of the body from ground level upward. The rest of the material was then thrown over the left shoulder and passed around the back, under the right arm, and once again over the left shoulder and arm. The right arm was therefore left free. The material could be pouched in front as well as drawn up over the head. Certain patterns and colours were worn by specific members of society.The basic masculine garment was like the chiton; it was called a tunica (tunic). Colours differentiated the social classes—white for the upper classes, natural or brown for others. Longer tunicas were worn for important occasions. About 190 CE the dalmatic was introduced from Dalmatia. This was a looser, ungirded style of tunic with wide sleeves.

Feminine dress was very like the Greek, with the Roman woman's version of the chiton called a stola. As time passed, women took to wearing several garments one on top of the other, while the garments themselves were made of finer fabrics and were more lavishly decorated. The feminine cloak, the palla, resembled the Greek himation.

Feminine dress was very like the Greek, with the Roman woman's version of the chiton called a stola. As time passed, women took to wearing several garments one on top of the other, while the garments themselves were made of finer fabrics and were more lavishly decorated. The feminine cloak, the palla, resembled the Greek himation.Underwear for both sexes consisted of a loincloth—like briefs—and women also wore a breastband—the mamillare. Footwear was based upon the Greek but was more varied. Apart from sandals, several styles of shoe and boot existed.

Face powder, rouge, eye shadow, and eyeliner were lavishly applied by upper-class women, who also attached beauty patches to their faces. Wigs and hair switches were commonly worn, and certain colours of hair were fashionable; for example, during the Gallic and Teutonic campaigns, blonde wigs made from the hair of captured slaves were in vogue.

Ancient nonclassical Europe

Animal furs (fur) and hides (hide) made up the chief garments during the European Stone Age. They would be held to the body by a thong belt and by pins at the shoulder. Later such skins were pierced with awls and sewn together with cordage to give a closer fit. Finds from tombs and living sites dating to the Upper Paleolithic Period (c. 38,000–c. 8,000 BCE) indicate that people had a fair knowledge of dressing skins, weaving, and sewing. No garments have survived the oldest part of the Upper Paleolithic, but archaeologists have recovered artifacts such as boxwood and bone combs, delicate bone needles, reindeer horn buttons and plaques, and decorative items such as necklaces and armlets of beads, amber, and ivory. Discoveries from more recent eras, such as that of the Iceman, (Iceman) or Ötzi (c. 3300 BCE), have provided more information.

Animal furs (fur) and hides (hide) made up the chief garments during the European Stone Age. They would be held to the body by a thong belt and by pins at the shoulder. Later such skins were pierced with awls and sewn together with cordage to give a closer fit. Finds from tombs and living sites dating to the Upper Paleolithic Period (c. 38,000–c. 8,000 BCE) indicate that people had a fair knowledge of dressing skins, weaving, and sewing. No garments have survived the oldest part of the Upper Paleolithic, but archaeologists have recovered artifacts such as boxwood and bone combs, delicate bone needles, reindeer horn buttons and plaques, and decorative items such as necklaces and armlets of beads, amber, and ivory. Discoveries from more recent eras, such as that of the Iceman, (Iceman) or Ötzi (c. 3300 BCE), have provided more information.The advent of the Bronze Age varies in time and expression from one part of Europe to another. The art of bronze working came to Italy from the Middle East and then spread westward to Britain and Scandinavia. During the years 1500–600 BCE the arts of spinning and weaving were further developed; simple natural dyes were used; and decoration was by embroidery, fringing, and plaiting.

In Denmark, the northern Netherlands, and Germany the practice of burying people in peat bogs has preserved a number of actual, almost complete, Bronze Age garments. Most of the garments are woolen or leather items that were maintained in remarkable condition in oak log coffins. They include large semicircular cloaks, felt caps, tunics with leather straps and belts, and, for women, jackets and skirts with ornamental belts and hair ornaments. Many of these are on display in the National Museum in Copenhagen and the Schleswig-Holstein Museum of Prehistory and Early History in Germany.

A different type of dress was worn by the nomadic peoples who lived on the Steppe (Steppe, the), a grassy plain that stretches from Hungary to Manchuria. Such groups, which included the Scythians (Scythian), Cimmerians (Cimmerian), and Sarmatians (Sarmatian), traveled immense distances on horseback. Their attire being suited to their way of life, both sexes wore similar garments consisting of a woolen tunic over a shirt and wide trousers. These garments were worn in layers one on top of another; they were fairly close-fitting but loose enough for comfort and for the practical needs of hours spent on horseback. Short boots were pulled up over the trouser bottoms and tied in place. These peoples also wore leather belts around their waists, and felted woolen caps kept their heads warm. Around 600 BCE the Scythians lived in the region around the Black Sea and then gradually moved westward to Romania, Hungary, and Germany. Excavation of their burial sites in the Dnieper valley and near Simferopol, both in Ukraine, and in the Balkans has yielded both actual garments and a wealth of relief sculpture, vases, and plaques that illustrate Scythian dress.

A different type of dress was worn by the nomadic peoples who lived on the Steppe (Steppe, the), a grassy plain that stretches from Hungary to Manchuria. Such groups, which included the Scythians (Scythian), Cimmerians (Cimmerian), and Sarmatians (Sarmatian), traveled immense distances on horseback. Their attire being suited to their way of life, both sexes wore similar garments consisting of a woolen tunic over a shirt and wide trousers. These garments were worn in layers one on top of another; they were fairly close-fitting but loose enough for comfort and for the practical needs of hours spent on horseback. Short boots were pulled up over the trouser bottoms and tied in place. These peoples also wore leather belts around their waists, and felted woolen caps kept their heads warm. Around 600 BCE the Scythians lived in the region around the Black Sea and then gradually moved westward to Romania, Hungary, and Germany. Excavation of their burial sites in the Dnieper valley and near Simferopol, both in Ukraine, and in the Balkans has yielded both actual garments and a wealth of relief sculpture, vases, and plaques that illustrate Scythian dress.The 6th-century-BCE Hallstatt culture of the Bavarian and Bohemian areas had an advanced lifestyle for its time. Finds from this early phase of the Iron Age, however, are chiefly weapons (weapon) and jewelry. In the 4th century BCE the Celts (Celt) from central Europe, or at least some of their styles and methods of manufacture, moved into Italy and thence on to Britain, Ireland, and Spain. Finds of the Celtic culture, which consist largely of jewelry, toilet articles, and ornaments, illustrate both the high Celtic standard of craftsmanship, especially in metal, and the individual character of their design. Museums in many countries—notably Italy, Spain, Portugal, Ireland, and Britain—display a wealth of such work.

Roman influence on the dress of the northern and western countries of the empire was strong until the early 5th century CE. This was to a certain extent, however, a two-way influence since, in the colder northern areas, the Romans found the indigenous dress styles of belted tunics (tunic) with trousers or leg-banding more suitable than their own Classical tunica and bare legs. Useful evidence of local attire in Britain, Gaul, and Germany is graphically illustrated on Trajan's Column and that of Marcus Aurelius, both in Rome. This evidence is reinforced by the written accounts of Roman historians such as Cornelius Tacitus (Tacitus) of the 1st century CE and Sidonius Apollinaris of the later years.

Roman influence on the dress of the northern and western countries of the empire was strong until the early 5th century CE. This was to a certain extent, however, a two-way influence since, in the colder northern areas, the Romans found the indigenous dress styles of belted tunics (tunic) with trousers or leg-banding more suitable than their own Classical tunica and bare legs. Useful evidence of local attire in Britain, Gaul, and Germany is graphically illustrated on Trajan's Column and that of Marcus Aurelius, both in Rome. This evidence is reinforced by the written accounts of Roman historians such as Cornelius Tacitus (Tacitus) of the 1st century CE and Sidonius Apollinaris of the later years.The pre-Columbian (pre-Columbian civilizations) Americas

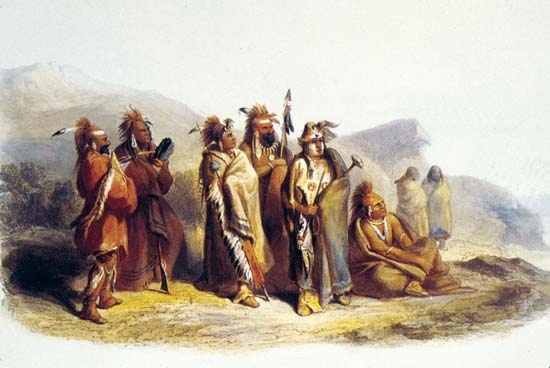

At the time of their first encounter with European explorers, the American Indian population was composed of societies of many levels of social and economic complexity. Cultural groups extended from the Eskimo (Inuit and Yupik/Yupiit) of the Arctic circle to the Maya, Aztec, and Inca of Central and South America. With such immense climatic variation, the Americas were home to a wide variety of dress.

Native Americans (American Indian)

Cloth was rarely made in the region north of the Rio Grande, although many cultures there made finely woven baskets. The California Indians (California Indian) and the Northwest Coast Indians (Northwest Coast Indian) also wove capes and hats from plant fibres.

Cloth was rarely made in the region north of the Rio Grande, although many cultures there made finely woven baskets. The California Indians (California Indian) and the Northwest Coast Indians (Northwest Coast Indian) also wove capes and hats from plant fibres. Most people wore clothing made from the tanned (tanning) or chamois skins of local animals, such as deer, elk, buffalo, moose, beaver, otter, wolf, fox, and squirrel. Native Americans (Native American) employed animal oils, particularly those found in the brains of the animal, to produce a softly textured material that they then dyed in brilliant colours. They often made use of the entire skin, adapting the garment to the shape of the animal and wearing it draped and sewn only minimally; the legs, paws, and tail were left attached and hung down as decoration. Two skins were often used for a woman's dress or man's tunic, one back and one front. Like other groups with little to no metalworking, Native Americans pierced the edges of skins with bone or stone awls and then threaded the edges together with animal sinew or fibre cordage. Decoration was by porcupine-quill embroidery (quillwork), the quills being softened by chewing or simmering and then dyed. Garments were also decorated by fringed edging.

Most people wore clothing made from the tanned (tanning) or chamois skins of local animals, such as deer, elk, buffalo, moose, beaver, otter, wolf, fox, and squirrel. Native Americans (Native American) employed animal oils, particularly those found in the brains of the animal, to produce a softly textured material that they then dyed in brilliant colours. They often made use of the entire skin, adapting the garment to the shape of the animal and wearing it draped and sewn only minimally; the legs, paws, and tail were left attached and hung down as decoration. Two skins were often used for a woman's dress or man's tunic, one back and one front. Like other groups with little to no metalworking, Native Americans pierced the edges of skins with bone or stone awls and then threaded the edges together with animal sinew or fibre cordage. Decoration was by porcupine-quill embroidery (quillwork), the quills being softened by chewing or simmering and then dyed. Garments were also decorated by fringed edging.Depending upon local conditions, men might wear a breechclout and women a short skirt. In warm, dry climates shirts were often optional, while in wetter regions a cloak or poncho might be added. In cooler areas men typically wore a loose hip-length tunic and thigh-length leggings, the latter tied to the waistband of the breechclout. Women typically wore a long dress and short leggings.

Hair was carefully tended by both sexes. For the men there were many, varied styles; in some areas hair was grown long and plaited, in others it was worn loose. Some styles were dramatic, consisting of, for example, a ridge of hair sticking up along the crown of the head, extending from the forehead back, with the remainder of the head shaved. (This style was revived in punk coiffures of more modern times when it was called the Mohawk or Mohican.) Animal hair and feathers (feather) were added to many hairstyles. An important form of regalia was a feathered headdress, which sometimes included buffalo horns, ermine tails, and quillwork. Women's hair was generally worn long, either loose, plaited, or held in place by a headband.

Hair was carefully tended by both sexes. For the men there were many, varied styles; in some areas hair was grown long and plaited, in others it was worn loose. Some styles were dramatic, consisting of, for example, a ridge of hair sticking up along the crown of the head, extending from the forehead back, with the remainder of the head shaved. (This style was revived in punk coiffures of more modern times when it was called the Mohawk or Mohican.) Animal hair and feathers (feather) were added to many hairstyles. An important form of regalia was a feathered headdress, which sometimes included buffalo horns, ermine tails, and quillwork. Women's hair was generally worn long, either loose, plaited, or held in place by a headband.The moccasin was the traditional shoe. It was made from one or two pieces of soft leather, which enclosed the foot, with no added heel. It was seamed to an inset decorative piece on top of the instep. The leather was then folded over at the back.

Facial and body hair was often plucked out with tweezers, and both face and hair were painted. Red pigment was frequently used to paint the body. Both sexes tattooed (tattoo) their bodies, sometimes all over, and some continue this tradition today; bright red and black were the colours most often used for this.

The Eskimo

The clothing of the Eskimo (Inuit and Yupik/Yupiit) and Aleut was adapted to the Arctic cold and had much in common with that worn in the Siberian Arctic. This clothing was made from animal skins, but because of the climate it was sewn and tailored to the body to keep out the wind. The fur or pelt of the animal was retained, and garments were often worn fur side in. Thread was of animal sinew, awls for piercing the skin were generally stone, and needles were of bone or ivory. The Eskimo used all available animal skins: polar bear, deer, caribou reindeer, antelope, dog, and fox. They also used birds—the skin for clothing and the feathers as decoration. Sealskin was ideal for boots, which were made with the fur turned inward. Seal gut was used to make waterproof outer garments for those who ventured onto the sea.

The clothing of the Eskimo (Inuit and Yupik/Yupiit) and Aleut was adapted to the Arctic cold and had much in common with that worn in the Siberian Arctic. This clothing was made from animal skins, but because of the climate it was sewn and tailored to the body to keep out the wind. The fur or pelt of the animal was retained, and garments were often worn fur side in. Thread was of animal sinew, awls for piercing the skin were generally stone, and needles were of bone or ivory. The Eskimo used all available animal skins: polar bear, deer, caribou reindeer, antelope, dog, and fox. They also used birds—the skin for clothing and the feathers as decoration. Sealskin was ideal for boots, which were made with the fur turned inward. Seal gut was used to make waterproof outer garments for those who ventured onto the sea.Both sexes wore the same type of garments: a hooded tunic or coat, trousers, and boots. The hooded tunic was variously named in different areas. Two of these—the parka of the Aleutian Islands and the anorak of Greenland—have become essential items of modern dress.

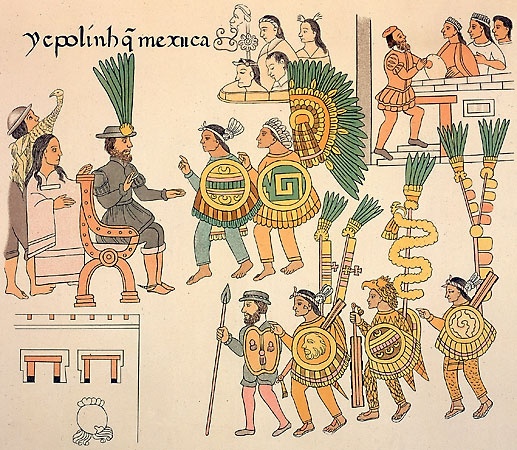

The Aztec, the Maya, and the Inca

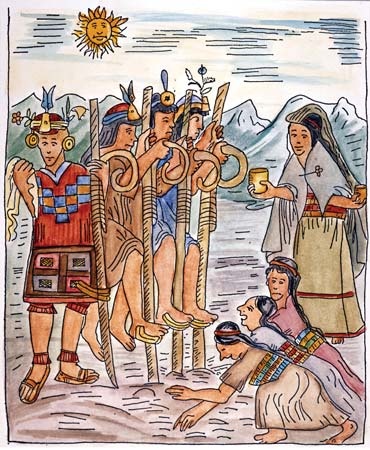

In Central (Central America) and South America (South American Indian) lived the Aztec, the Maya, and the Inca. The Aztec settled in Mexico about the 12th century. Their capital city, Tenochtitlán, which they established in the 14th century, was on the present-day site of Mexico City. The men wore loincloths, the women tunics and skirts, all made from woven cotton fabric. Ornamental cloaks were worn as garments of rank. The decoration of Aztec costume was chiefly by exotic plumes, but fur also was used. The Aztec elite wore a great deal of jewelry, mainly of gold.

In Central (Central America) and South America (South American Indian) lived the Aztec, the Maya, and the Inca. The Aztec settled in Mexico about the 12th century. Their capital city, Tenochtitlán, which they established in the 14th century, was on the present-day site of Mexico City. The men wore loincloths, the women tunics and skirts, all made from woven cotton fabric. Ornamental cloaks were worn as garments of rank. The decoration of Aztec costume was chiefly by exotic plumes, but fur also was used. The Aztec elite wore a great deal of jewelry, mainly of gold. The Maya came to Guatemala about 800 BCE and spread into the Yucatán Peninsula. Their culture flourished chiefly between 250 and 900 CE. They also wore few garments: a loincloth for men and a cloak when needed; a loose sleeveless dress or blouse and skirt for women. Cotton and sisal were cultivated; women were responsible for spinning and weaving these fibres. The Maya also developed a method of tie-dyeing the yarn and of weaving patterns using bright colours for dyes. Embroidery also was practiced.

The Maya came to Guatemala about 800 BCE and spread into the Yucatán Peninsula. Their culture flourished chiefly between 250 and 900 CE. They also wore few garments: a loincloth for men and a cloak when needed; a loose sleeveless dress or blouse and skirt for women. Cotton and sisal were cultivated; women were responsible for spinning and weaving these fibres. The Maya also developed a method of tie-dyeing the yarn and of weaving patterns using bright colours for dyes. Embroidery also was practiced. Cotton fabrics were mainly reserved for upper-class wear, as were beautifully decorated leather belts and sandals. For the ordinary people, tapa—a cloth derived from tree bark, as in Polynesia—was made. An important part of Mayan decoration was provided by feathers from birds of brilliant plumage, which were skillfully incorporated into the weaving processes. The feathers were also widely used in the ornamentation of headdresses. The long, iridescent tail feathers of the quetzal, a member of the trogon family of birds, were especially prized, as they were in Aztec dress.

Cotton fabrics were mainly reserved for upper-class wear, as were beautifully decorated leather belts and sandals. For the ordinary people, tapa—a cloth derived from tree bark, as in Polynesia—was made. An important part of Mayan decoration was provided by feathers from birds of brilliant plumage, which were skillfully incorporated into the weaving processes. The feathers were also widely used in the ornamentation of headdresses. The long, iridescent tail feathers of the quetzal, a member of the trogon family of birds, were especially prized, as they were in Aztec dress. The Inca came from the valley of Cuzco in the high mountains of Peru. During the 15th century they established a powerful empire of several million people in what are now Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador, and extending into parts of Argentina and Chile. Their attire was brightly coloured and decorated by feathers—indeed some of their fine cloaks were made entirely of feathers woven into a cotton fabric base. They kept herds of llamas (llama) for wool and hunted other animals, such as the chinchilla, for their fur. Nonetheless, Inca garments were simple in construction: a basic loincloth for both sexes and, over this, a short tunic for men and an ankle-length dress for women. The poncho was the most usual cloak. People went barefoot or wore sandals. They also frequently went bareheaded or, in bad weather, adopted a woolen cap or turban.

The Inca came from the valley of Cuzco in the high mountains of Peru. During the 15th century they established a powerful empire of several million people in what are now Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador, and extending into parts of Argentina and Chile. Their attire was brightly coloured and decorated by feathers—indeed some of their fine cloaks were made entirely of feathers woven into a cotton fabric base. They kept herds of llamas (llama) for wool and hunted other animals, such as the chinchilla, for their fur. Nonetheless, Inca garments were simple in construction: a basic loincloth for both sexes and, over this, a short tunic for men and an ankle-length dress for women. The poncho was the most usual cloak. People went barefoot or wore sandals. They also frequently went bareheaded or, in bad weather, adopted a woolen cap or turban.The Middle East (Middle East, ancient) from the 6th century

The style of costume worn throughout the Middle East has been remarkably constant for centuries. This is partly because it has evolved as one suited to the climate, serving as a protection against heat, dust, and blazing sunshine. The wearing of traditional clothing has also been accepted and supported by many Muslim (Islām) countries.

The traditional garments of the Middle East are loose-fitting and cover or even envelop much of the body. The names of these garments vary from country to country, but the similarity between them is clear. Likewise the materials from which they were, and still are, made vary according to what is available. In general, linen, cotton, and wool are the norm, but the well-to-do have always worn garments made from rich fabrics with a silk base. Several of the most famous of these materials originated in this area, including baldachin, the richly decorated fabric with a warp of gold thread and a weft of silk, named after the city of Baghdad, and damask, named after Damascus (in Syria), the source of this richly patterned silk fabric.

A number of the traditional garments were originally derived from ancient cultures in the region, particularly from Persia (Iran) and farther east in India, Mongolia, and Asian (Asia) Russia. The caftan is one such example. It is an open, coatlike garment, termed in ancient Persia a candys or kandys. Also worn extensively in the cooler climates of Mongolia and China, the style extended westward to become, eventually, the fashionable dolman of the late Ottoman Empire.

A number of the traditional garments were originally derived from ancient cultures in the region, particularly from Persia (Iran) and farther east in India, Mongolia, and Asian (Asia) Russia. The caftan is one such example. It is an open, coatlike garment, termed in ancient Persia a candys or kandys. Also worn extensively in the cooler climates of Mongolia and China, the style extended westward to become, eventually, the fashionable dolman of the late Ottoman Empire.The spread of the characteristic costume of the Middle East was due in large part to the spread of Arab peoples and cultures. The people of the Arabian Desert were by the 6th century CE leading a stable, rural life in the border areas of Yemen, Syria, and Iraq; in the interior region they were largely Bedouin nomads raising camel herds for a living. By 750 CE the Arab empire extended from Spain and Morocco in the west to the Caspian Sea and the Indus River in the east. The chief garments worn at that time were a loose shirt, chemise, or robe; a draped cloak; wide, baggy trousers; and a head cloth or turban. Similar versions of these may still be seen on the streets of Cairo, Istanbul, or Damascus.

The simple basic garment for both sexes was a loose, long shirt, chemise, or tunic, which often had long sleeves. Over this men wore a robe or mantle of various types. The aba (ʿabāʾ or abaya) was of ancient origin and is mentioned in the Bible as the attire of Hebrew prophets. It was traditionally made of heavy cream-coloured wool decorated with brightly coloured stripes or embroidery. A voluminous outer gown still worn throughout the Middle East in the Arab world is the jellaba, known as the jellabah in Tunisia, a jubbeh in Syria, a gallibiya in Egypt, or a dishdasha in Algeria. The garment generally has wide, long sleeves, and the long skirt may be slit up the sides; some styles are open in front like a coat or caftan.

The simple basic garment for both sexes was a loose, long shirt, chemise, or tunic, which often had long sleeves. Over this men wore a robe or mantle of various types. The aba (ʿabāʾ or abaya) was of ancient origin and is mentioned in the Bible as the attire of Hebrew prophets. It was traditionally made of heavy cream-coloured wool decorated with brightly coloured stripes or embroidery. A voluminous outer gown still worn throughout the Middle East in the Arab world is the jellaba, known as the jellabah in Tunisia, a jubbeh in Syria, a gallibiya in Egypt, or a dishdasha in Algeria. The garment generally has wide, long sleeves, and the long skirt may be slit up the sides; some styles are open in front like a coat or caftan.Outer gowns or cloaks sometimes incorporated head coverings. These included the haik, which was an oblong piece of material (generally striped) that the Arabs used to wrap around their bodies and heads for day or night wear; the material measured about 18 feet by 6 feet (5.5 by 1.8 metres). A similar mantle was the burnous, a hooded garment also used for warmth day or night.

The loose, baggy trousers traditional to the Middle East, as well as to the Balkans and Anatolia, are still widely worn by both sexes. The garment is believed to have originated in Persia, and it is presumed that the Arabs saw it there when they invaded that country in the 7th century. The trousers, called chalvar, chalwar, or ṣalvar according to the country where they were worn, measured about 3 yards (2.75 metres) across at the waist and were drawn tight by cords. The full, leg portion was tied at each ankle. A broad sash then encircled the waist, on top of the chalvar. Worn in this way the garment was ideal for working in the fields because it allowed freedom of movement and protected the lumbar region of the spine, especially while bending, from chills. For centuries the garment has also been adopted by men in the fighting forces. Cotton is the usual material for working attire, but fashionable ladies wear a chalvar made from a brocade or silk fabric over linen drawers.

The loose, baggy trousers traditional to the Middle East, as well as to the Balkans and Anatolia, are still widely worn by both sexes. The garment is believed to have originated in Persia, and it is presumed that the Arabs saw it there when they invaded that country in the 7th century. The trousers, called chalvar, chalwar, or ṣalvar according to the country where they were worn, measured about 3 yards (2.75 metres) across at the waist and were drawn tight by cords. The full, leg portion was tied at each ankle. A broad sash then encircled the waist, on top of the chalvar. Worn in this way the garment was ideal for working in the fields because it allowed freedom of movement and protected the lumbar region of the spine, especially while bending, from chills. For centuries the garment has also been adopted by men in the fighting forces. Cotton is the usual material for working attire, but fashionable ladies wear a chalvar made from a brocade or silk fabric over linen drawers. The tradition for women to cover themselves from head to toe and veil (purdah) their faces when they go out in public is an old one, predating Islam in Persia, Syria, and Anatolia. The Qurʾān provides instructions giving guidance on this matter but not a strict ruling. However, some modern regimes have insisted on the strict veiling of women in public. The enveloping cloaks worn by women for this purpose are similar to one another and often incorporate a mesh panel through which women may peer at the world outside. The most common names for this garment are burka, chador, chādar, chadri, çarşaf, and tcharchaf.

The tradition for women to cover themselves from head to toe and veil (purdah) their faces when they go out in public is an old one, predating Islam in Persia, Syria, and Anatolia. The Qurʾān provides instructions giving guidance on this matter but not a strict ruling. However, some modern regimes have insisted on the strict veiling of women in public. The enveloping cloaks worn by women for this purpose are similar to one another and often incorporate a mesh panel through which women may peer at the world outside. The most common names for this garment are burka, chador, chādar, chadri, çarşaf, and tcharchaf. The characteristic masculine Arab headdress has been the kaffiyeh. It is still worn today, although it may now accompany a business suit. Basically, the kaffiyeh is a square of cotton, linen, wool, or silk, either plain or patterned, that is folded into a triangle and placed upon the head so that one point falls on to each shoulder and the third down the back. It is held in place on the head by the agal (igal, egal), a corded band decorated with beads or metallic threads.

The characteristic masculine Arab headdress has been the kaffiyeh. It is still worn today, although it may now accompany a business suit. Basically, the kaffiyeh is a square of cotton, linen, wool, or silk, either plain or patterned, that is folded into a triangle and placed upon the head so that one point falls on to each shoulder and the third down the back. It is held in place on the head by the agal (igal, egal), a corded band decorated with beads or metallic threads.Footwear was in the form of sandals, shoes, or boots, with the toes slightly turned up. Women traditionally wore decorative wooden pattens called kub-kobs to walk about in muddy unpaved streets.

The Byzantine Empire

In 324 CE the Roman emperor Constantine I decided to rebuild the great city at Byzantium, then a Greek centre. The city was sited strategically on the Bosporus, whose narrow waters connecting the Mediterranean and the Black Sea acted as a gateway between West and East. Constantine called his city New Rome; it was later renamed Constantinople (now Istanbul) in his honour. After the collapse of the western part of the Roman Empire, which was based in Rome (and later Ravenna), Constantinople became the capital city of the Christian-dominated Byzantine Empire, the extent of which fluctuated considerably until its collapse in 1453.

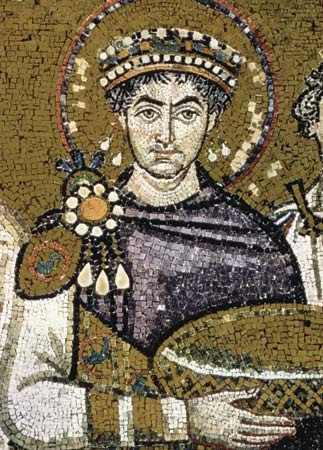

Owing to the site of its capital city, the empire was subject to a complex of influences that were nowhere more marked than in the dress of its ruling classes. Over the centuries there were two notable periods of wealth and prosperity that were reflected in costume. The first period was in the time of the emperor Justinian I, who reigned from 527 to 565 CE. Until this time the influence of Rome was still strong, and dress styles tended to be draped in the fashion of the later years of the empire. There were differences, however, derived in part from Persian and Anatolian designs, such as the use of sewn, closer-fitting garments and richer ornamentation and jewelry. In addition, because of its success as a trade centre between East and West, the Byzantine Empire had become extremely wealthy. This wealth led to a costume of magnificent splendour that became the envy of the known world. Luxury fabrics from Asia, Syria, and Egypt became available in quantity and were utilized, despite the high cost, by the leading members of society.

Owing to the site of its capital city, the empire was subject to a complex of influences that were nowhere more marked than in the dress of its ruling classes. Over the centuries there were two notable periods of wealth and prosperity that were reflected in costume. The first period was in the time of the emperor Justinian I, who reigned from 527 to 565 CE. Until this time the influence of Rome was still strong, and dress styles tended to be draped in the fashion of the later years of the empire. There were differences, however, derived in part from Persian and Anatolian designs, such as the use of sewn, closer-fitting garments and richer ornamentation and jewelry. In addition, because of its success as a trade centre between East and West, the Byzantine Empire had become extremely wealthy. This wealth led to a costume of magnificent splendour that became the envy of the known world. Luxury fabrics from Asia, Syria, and Egypt became available in quantity and were utilized, despite the high cost, by the leading members of society.The domestic textile industry was also stimulated. Its development was greatly aided by the introduction of sericulture into Constantinople. The Chinese had guarded secrets of the manufacture of silk for hundreds of years, but by about 1000 BCE silkworm culture and silk manufacture had been established in northern India, and the knowledge later percolated through to Korea, Japan, Persia, and Central Asia. Justinian had tried early in his reign to divert the silk trade (international trade) from its route from Persia but without success. He was presented with a tremendous opportunity when two Persian monks, who had worked as missionaries in China and had studied the process of sericulture and the weaving of the filaments, agreed to smuggle this knowledge, as well as the necessary silkworm (silkworm moth) eggs, to Constantinople in exchange for a large monetary reward. Silkworms flourished in Constantinople, and the authorities there, like the Chinese and others before them, guarded the secrets of the process and controlled their monopoly in Europe until, inevitably, in the early Middle Ages, the knowledge and means were once more disseminated, this time to Anatolia and Sicily and from there gradually to Italy and France.

During Justinian's reign, Byzantine textile manufacturers produced beautiful, glamorous fabrics, mainly of silk interwoven with gold and silver metallic threads and interspersed with pearls and jeweled embroideries. The use of these heavy lustrous fabrics gradually altered the style of dress; the stiff, ornate materials lent themselves to a simpler cut with only a few folds to break up the often allover, large-motif designs. For both men and women a more fitted, sewn tunic, cinched at the waist by a richly decorated wide belt and hanging straight to knee or ankle, replaced the Roman draped tunica (tunic). A rich, deep decorative collar, like the preceding Egyptian and Etruscan versions, covered the shoulders. The influence of the Christian church could be seen in the fact that the limbs were generally covered by long, usually fitted sleeves and cloth or silken hose. Cloaks, pinned at the shoulder, were worn outdoors. Imperial dress was characterized by the extensive use of purple and gold. Garments for the wealthy were vividly coloured in reds, yellows, and greens. Such attire is depicted in the 6th-century mosaics and the Ravenna churches of San Vitale and Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, which include portraits of Justinian and his wife, Theodora.

During Justinian's reign, Byzantine textile manufacturers produced beautiful, glamorous fabrics, mainly of silk interwoven with gold and silver metallic threads and interspersed with pearls and jeweled embroideries. The use of these heavy lustrous fabrics gradually altered the style of dress; the stiff, ornate materials lent themselves to a simpler cut with only a few folds to break up the often allover, large-motif designs. For both men and women a more fitted, sewn tunic, cinched at the waist by a richly decorated wide belt and hanging straight to knee or ankle, replaced the Roman draped tunica (tunic). A rich, deep decorative collar, like the preceding Egyptian and Etruscan versions, covered the shoulders. The influence of the Christian church could be seen in the fact that the limbs were generally covered by long, usually fitted sleeves and cloth or silken hose. Cloaks, pinned at the shoulder, were worn outdoors. Imperial dress was characterized by the extensive use of purple and gold. Garments for the wealthy were vividly coloured in reds, yellows, and greens. Such attire is depicted in the 6th-century mosaics and the Ravenna churches of San Vitale and Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, which include portraits of Justinian and his wife, Theodora.The second period of expansion and prosperity came between the 9th and 11th centuries. Court dress became richer than ever, encrusted with jeweled embroideries and dyed in deep colours, especially purples and reds. Imperial dress included a long panel of gold-embroidered material, which was wrapped around the body with the end hung over one arm. The classical line had completely given place to an Eastern form of dress. For example, the caftan had been adopted as formal wear. Open down the centre front, this coatlike garment was shaped to fit at the back. For both sexes the caftan was accompanied by trousers, not full like the Middle Eastern chalvar but more elegantly and closely cut, especially on the lower limbs where they were tucked into boot tops or worn over shoes.

Byzantine dress strongly influenced that of eastern Europe, especially the Balkans and Russia. Some of the bejeweled silk formal garments were gradually adopted by the church to become vestments in the Middle Ages.

Men tended to prefer leather boots in footwear, black for normal use and red at court. Women sometimes wore sandals but more often were found in soft, ankle-height shoes, brightly coloured and embroidered.

Masculine hairstyles were short, and men were mostly clean-shaven. Outdoors they adopted the Phrygian cap or a hood. Women wore veils and often encased their long hair in a silk cap or a pearl net. Elaborate jewelry was characteristic of all Byzantine dress of the upper classes. Perfume was liberally applied but cosmetics less so.

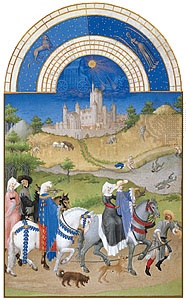

Medieval (Middle Ages) Europe