Trail of Tears

United States history

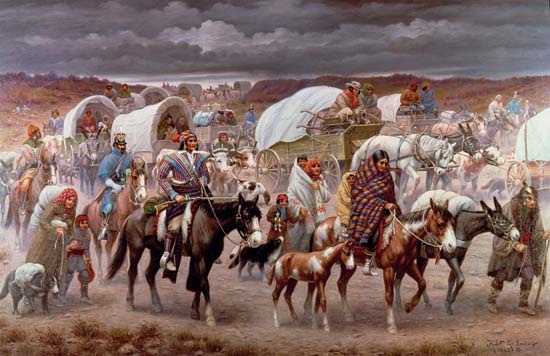

in U.S. history, the forced relocation during the 1830s of Eastern Woodlands Indians to areas west of the Mississippi River. Estimates based on tribal and military records suggest that approximately 100,000 indigenous people were forced from their homes during this period, which is sometimes known as the removal era, and that some 15,000 died during the journey west. The term Trail of Tears invokes the collective suffering these people experienced, although it is most commonly used in reference to the removal experiences of the Southeast Indians (Southeast Indian) generally and the Cherokee nation specifically.

in U.S. history, the forced relocation during the 1830s of Eastern Woodlands Indians to areas west of the Mississippi River. Estimates based on tribal and military records suggest that approximately 100,000 indigenous people were forced from their homes during this period, which is sometimes known as the removal era, and that some 15,000 died during the journey west. The term Trail of Tears invokes the collective suffering these people experienced, although it is most commonly used in reference to the removal experiences of the Southeast Indians (Southeast Indian) generally and the Cherokee nation specifically.The roots of forced relocation lay in greed. The British Proclamation of 1763 (1763, Proclamation of) designated the region between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River as Indian Territory. Although this region was to be protected for the exclusive use of indigenous peoples, large numbers of Euro-American land speculators and settlers soon entered. For the most part, the British and, later, American governments ignored these acts of trespass.

In 1829 a gold rush occurred on Cherokee land in Georgia. Vast amounts of wealth were at stake: at their peak, Georgia mines produced approximately 300 ounces of gold a day. Land speculators soon demanded that the U.S. Congress devolve to the states the control of all real property owned by tribes and their members. This position was supported by Pres. Andrew Jackson (Jackson, Andrew), who was himself an avid speculator. Congress complied by passing the Indian Removal Act (1830). The act entitled the president to negotiate with the eastern nations to effect their removal to tracts of land west of the Mississippi and provided some $500,000 for transportation and for compensation to native landowners. Jackson reiterated his support for the act in various messages to Congress, notably On Indian Removal (Andrew Jackson: On Indian Removal) (1830) and A Permanent Habitation for the American Indians (Andrew Jackson: A Permanent Habitation for the American Indians) (1835), which illuminated his political justifications for removal and described some of the outcomes he expected would derive from the relocation process.

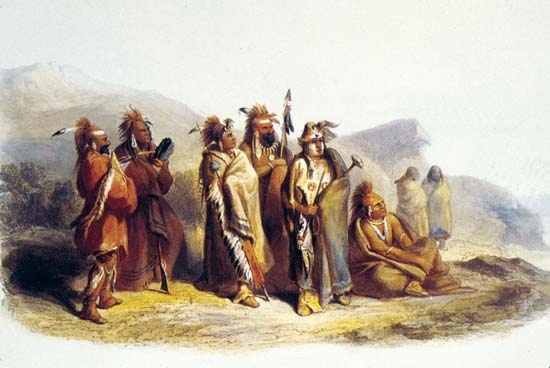

Indigenous reactions to the Indian Removal Act varied. The Southeast Indians (Southeast Indian) were for the most part tightly organized and heavily invested in agriculture. The farms of the most populous tribes—the Choctaw, Creek, Chickasaw, Seminole, and Cherokee—were particularly coveted by outsiders because they were located in prime agricultural areas and were very well developed. This meant that speculators who purchased such properties could immediately turn a profit: fields had already been cleared, pastures fenced, barns and houses built, and the like. Thus, the Southeast tribes approached federal negotiations with the goal of either reimbursement for or protection of their members' investments.

Indigenous reactions to the Indian Removal Act varied. The Southeast Indians (Southeast Indian) were for the most part tightly organized and heavily invested in agriculture. The farms of the most populous tribes—the Choctaw, Creek, Chickasaw, Seminole, and Cherokee—were particularly coveted by outsiders because they were located in prime agricultural areas and were very well developed. This meant that speculators who purchased such properties could immediately turn a profit: fields had already been cleared, pastures fenced, barns and houses built, and the like. Thus, the Southeast tribes approached federal negotiations with the goal of either reimbursement for or protection of their members' investments.The Choctaw were the first polity to finalize negotiations: in 1830 they agreed to cede their real property for western land, transportation for themselves and their goods, and logistical support during and after the journey. However, the federal government had no experience in transporting large numbers of civilians, let alone their household effects, farming equipment, and livestock. Bureaucratic ineptitude and corruption caused many Choctaw to die from exposure, malnutrition, exhaustion, and disease while traveling.

The Chickasaw signed an initial removal agreement as early as 1830, but negotiations were not finalized until 1832. Skeptical of federal assurances regarding reimbursement for their property, members of the Chickasaw nation sold their landholdings at a profit and financed their own transportation. As a result, their journey, which took place in 1837, had fewer problems than did those of the other Southeast tribes.

The Creek also finalized a removal agreement in 1832. However, Euro-American settlers and speculators moved into the planned Creek cessions prematurely, causing conflicts, delays, and fraudulent land sales that delayed the Creek journey until 1836. Federal authorities once again proved incompetent and corrupt, and many Creek people died, often from the same preventable causes that had killed Choctaw travelers.

A small group of Seminole leaders negotiated a removal agreement in 1832, but a majority of the tribe protested that the signatories had no authority to represent them. The United States insisted that the agreement should hold, instigating such fierce resistance to removal that the ensuing conflict became known as the Second Seminole War (Seminole Wars) (1835–42). Although many were eventually captured and removed to the west, a substantial number of Seminole people managed to elude the authorities and remain in Florida.

The Cherokee chose to use legal action to resist removal. Their lawsuits, notably Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) and Worcester v. Georgia (1832), reached the U.S. Supreme Court but ultimately provided no relief. As with the Seminole, a few Cherokee leaders negotiated a removal agreement that was subsequently rejected by the people as a whole. Although several families moved west in the mid-1830s, most believed that their property rights would ultimately be respected. This was not the case, and in 1838 the U.S. military began to force Cherokee people from their homes, often at gunpoint. Held in miserable internment camps for days or weeks before their journeys began, many became ill, and most were very poorly equipped for the arduous trip. Perhaps 4,000 of the estimated 15,000 Cherokee died on the journey, while some 1,000 avoided internment and built communities in North Carolina.

Traditionally, the Northeast Indian nations tended to be more mobile and less politically unified than those of the Southeast. As a result, literally dozens of band-specific removal agreements were negotiated with the peoples of this region between 1830 and 1840. Many of the groups residing in the coniferous forests of the Upper Midwest, such as various bands of Ojibwa and Ho-Chunk, agreed to cede particular tracts of land but retained in perpetuity the right to hunt, fish, and gather wild plants and timber from such properties. Groups living in the prairies and deciduous forests of the Lower Midwest, including bands of Sauk, Fox, Iowa, Illinois, and Potawatomi, ceded their land with great reluctance and were moved west in small parties, usually under pressure from speculators, settlers, and the U.S. military. A few groups attempted armed resistance, most notably a band led by the Sauk leader Black Hawk in 1832. Although their experiences are often overshadowed by those of the more populous Southeast nations, the peoples of the Northeast constituted perhaps one-third to one-half of those who were subject to removal.

Traditionally, the Northeast Indian nations tended to be more mobile and less politically unified than those of the Southeast. As a result, literally dozens of band-specific removal agreements were negotiated with the peoples of this region between 1830 and 1840. Many of the groups residing in the coniferous forests of the Upper Midwest, such as various bands of Ojibwa and Ho-Chunk, agreed to cede particular tracts of land but retained in perpetuity the right to hunt, fish, and gather wild plants and timber from such properties. Groups living in the prairies and deciduous forests of the Lower Midwest, including bands of Sauk, Fox, Iowa, Illinois, and Potawatomi, ceded their land with great reluctance and were moved west in small parties, usually under pressure from speculators, settlers, and the U.S. military. A few groups attempted armed resistance, most notably a band led by the Sauk leader Black Hawk in 1832. Although their experiences are often overshadowed by those of the more populous Southeast nations, the peoples of the Northeast constituted perhaps one-third to one-half of those who were subject to removal.In 1987 the U.S. Congress designated the Trail of Tears as a National Historic Trail in memory of those who suffered and died during removal. The trail includes some 2,200 miles (3,500 km) of routes over land and water.

Additional Reading

Reviews of the causes and effects of Indian removal include David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler, Indian Removal (2007); and Ronald N. Satz, American Indian Policy in the Jacksonian Era (2002). Theda Perdue and Michael D. Green, The Cherokee Nation and the Trail of Tears (2007), provides a case study of the experiences of a Southeast Indian nation; while Laurence M. Hauptman and L. Gordon McLester III (eds.), The Oneida Indian Journey: From New York to Wisconsin, 1784–1860 (1999), provides an example from the Northeast nations. Vicki Rozema (ed.), Voices from the Trail of Tears (2003), relates eyewitness accounts of the journey, gleaned from newspapers and other sources. Photographs of parts of the trail can be found in David G. Fitzgerald and Duane H. King, The Cherokee Trail of Tears (2007).