Fabales

plant order

Introduction

order of dicotyledonous flowering plants in the Rosid I group among the core eudicots. The order comprises 4 families ( Fabaceae, Polygalaceae, Quillajaceae, and Surianaceae), 754 genera, and more than 20,000 species. However, more than 95 percent of the genera and species belong to Fabaceae, the legume family. Fabaceae is the third largest family of angiosperms (angiosperm), exceeded only by Asteraceae (aster or sunflower family) and Orchidaceae ( orchid family). Along with Poaceae (the grass family), Fabaceae is the most important plant family in the production of food for humans and livestock, as well as in the production of industrial products.

order of dicotyledonous flowering plants in the Rosid I group among the core eudicots. The order comprises 4 families ( Fabaceae, Polygalaceae, Quillajaceae, and Surianaceae), 754 genera, and more than 20,000 species. However, more than 95 percent of the genera and species belong to Fabaceae, the legume family. Fabaceae is the third largest family of angiosperms (angiosperm), exceeded only by Asteraceae (aster or sunflower family) and Orchidaceae ( orchid family). Along with Poaceae (the grass family), Fabaceae is the most important plant family in the production of food for humans and livestock, as well as in the production of industrial products. Because they develop bacteria-harbouring root nodules that maintain the nitrogen balance in the soil, which is necessary for plant growth, the legumes are also an essential element in nature and in agriculture. Legumes are perhaps best known by their more common cultivated names, such as peas (pea), beans (bean), soybeans (soybean), peanuts (peanut) (groundnuts), alfalfa (lucerne), and clover. The characteristic fruit of most legumes is a pod (legume) consisting, in essence, of an ovary that is a tightly folded leaf, as in a pea pod. The pod normally splits into two halves when mature.

Because they develop bacteria-harbouring root nodules that maintain the nitrogen balance in the soil, which is necessary for plant growth, the legumes are also an essential element in nature and in agriculture. Legumes are perhaps best known by their more common cultivated names, such as peas (pea), beans (bean), soybeans (soybean), peanuts (peanut) (groundnuts), alfalfa (lucerne), and clover. The characteristic fruit of most legumes is a pod (legume) consisting, in essence, of an ovary that is a tightly folded leaf, as in a pea pod. The pod normally splits into two halves when mature.Distribution and abundance

Fabaceae, with about 730 genera and nearly 20,000 species, occurs in all terrestrial habitats occupied by plants, although the greatest number of species is in the tropics, where the group probably originated. There are also many legumes in the temperate plains, woodlands, and deserts. A few succeed as weeds in farming, industrial, and urban environments. They are less common in the northern boreal forests (boreal forest) and are rare in aquatic habitats. Beyond their natural occurrence, many legumes—e.g., Glycine max (soybeans) and Phaseolus (several species of beans)—are cultivated every year on a single vast area of land. Many species are seeded as pasture components; others are planted for soil improvement or to prevent erosion; woody species are grown for firewood and timber in developing countries; and dozens of species are popular ornamentals. Thus, legumes are cosmopolitan, not only in the wild but also in the human environment that has replaced the wilderness throughout much of the world.

Polygalaceae, the milkwort family, is the second largest family in the order, with about 21 genera and some 1,000 species. Its members are distributed worldwide, except for the Arctic and New Zealand. The genus Polygala contains about a third of the species in the family.

Polygalaceae, the milkwort family, is the second largest family in the order, with about 21 genera and some 1,000 species. Its members are distributed worldwide, except for the Arctic and New Zealand. The genus Polygala contains about a third of the species in the family.Surianaceae, with five genera and eight species, is restricted to Australia (Cadellia, Guilfoylia, and Stylobasium), Mexico (Recchia), and pantropical littoral areas (Suriana). Quillajaceae, with one genus (Quillaja) and three species, is restricted to temperate South America.

Characteristic morphological features

Members of Fabaceae include trees, herbaceous or woody vines, and perennial or annual herbs. The leaves are usually compound, and in some the leaflets are secondarily compound. The simple leaves of some are presumably reduced from the compound forms. The most striking of these modified leaf forms are the several hundred species of Australian acacia, in which the apparently simple leaf represents the flattened and modified axis of a compound leaf. Stipules, a pair of appendages subtending the leaf petiole, are usually present.

The flowers (flower) may be solitary or bunched in leaf axils. The inflorescences (inflorescence), when present, are of various kinds, simple or branched in diverse ways. The flowers are usually bisexual, but unisexual flowers occur sporadically throughout the family. Some legumes produce two kinds of flowers, commonly on the same plant. The typical kind have conspicuous petals that open so that cross-pollination (in some, an obligatory mechanism of propagation) is possible (chasmogamous); in others all parts are reduced and the petals do not open, thus enforcing self-pollination (cleistogamous). In the chasmogamous flowers, the sepals are most commonly partly fused, and the five petals alternate in position with the sepals. There are commonly 10 stamens, but there may be fewer or more. The stamens may remain free or they may be fused into a single tubular structure (monadelphous) or into a group of nine united stamens with a free stamen above this (diadelphous).

Most of these floral features, however, also can be found in other plant families. It is the pistil, or gynoecium, of Fabales that is unique. The single carpel develops into a fruit (the pod, or legume) that generally splits open (dehisces) along one or both edges (sutures) at maturity, releasing the seeds that have developed from the ovules. This basic legume type is idealized in a pea or bean pod, which bears two rows of marginally placed ovules along the upper suture. But evolution within the family has variously modified many legume fruits, and they bear but scant resemblance to that of a bean or pea. Some retain the form of the basic type but do not split open when ripe (indehiscent), as with Robinia (locusts) and Cercis (redbud). In many Fabaceae—for instance, Melilotus (sweet clover)—the fruit has been reduced to a single-seeded indehiscent structure that resembles a tiny nutlet. In others, it is several-seeded and indehiscent but is divided transversely into single-seeded segments that break apart at maturity (e.g., Desmodium). In another variant, the fruit coat becomes fleshy and plumlike as in the tropical Andira inermis (angelin tree). There are species in which the fruit is flattened and winged, facilitating wind transport. A few legumes have fruits that are produced or that mature underground; the peanut (Arachis hypogaea) is the best-known example. The peanut flower is actually produced above ground but assumes a position close to the soil surface as it ages. The ovary elongates and develops as a subterranean pod. All of these and other modifications are derivative and can be traced back to the basic, dehiscent pod of the pea or bean.

Most of these floral features, however, also can be found in other plant families. It is the pistil, or gynoecium, of Fabales that is unique. The single carpel develops into a fruit (the pod, or legume) that generally splits open (dehisces) along one or both edges (sutures) at maturity, releasing the seeds that have developed from the ovules. This basic legume type is idealized in a pea or bean pod, which bears two rows of marginally placed ovules along the upper suture. But evolution within the family has variously modified many legume fruits, and they bear but scant resemblance to that of a bean or pea. Some retain the form of the basic type but do not split open when ripe (indehiscent), as with Robinia (locusts) and Cercis (redbud). In many Fabaceae—for instance, Melilotus (sweet clover)—the fruit has been reduced to a single-seeded indehiscent structure that resembles a tiny nutlet. In others, it is several-seeded and indehiscent but is divided transversely into single-seeded segments that break apart at maturity (e.g., Desmodium). In another variant, the fruit coat becomes fleshy and plumlike as in the tropical Andira inermis (angelin tree). There are species in which the fruit is flattened and winged, facilitating wind transport. A few legumes have fruits that are produced or that mature underground; the peanut (Arachis hypogaea) is the best-known example. The peanut flower is actually produced above ground but assumes a position close to the soil surface as it ages. The ovary elongates and develops as a subterranean pod. All of these and other modifications are derivative and can be traced back to the basic, dehiscent pod of the pea or bean. Seeds (seed and fruit) within the legumes are also variable, ranging from the size of a pinhead to that of a baseball. Legume seeds are sometimes quite colourful; the Abrus precatorius (jequirity bean) ( jequirity bean) and Ormosia species, for example, produce striking black and red seeds. These seeds have been used as currency by native peoples and in the production of beads and handbags, especially in the more tropical regions. They may be quite poisonous if eaten, however.

Seeds (seed and fruit) within the legumes are also variable, ranging from the size of a pinhead to that of a baseball. Legume seeds are sometimes quite colourful; the Abrus precatorius (jequirity bean) ( jequirity bean) and Ormosia species, for example, produce striking black and red seeds. These seeds have been used as currency by native peoples and in the production of beads and handbags, especially in the more tropical regions. They may be quite poisonous if eaten, however.Polygalaceae contains trees, shrubs, and even parasitic herbs that lack green chlorophyll. Leaves are usually spirally arranged, simple, and without toothed margins. The flowers are bisexual, usually strongly irregular in shape, and superficially similar to legume flowers of Fabaceae. Flowers are arranged in spikes, racemes, or panicles. Two of the five sepals are often petaloid. The three or five petals are often fused to the anthers to form a tube, and the stamens often open by terminal slits. Fruits that develop are quite variable in structure, including capsules, nuts, winged samaras, and fleshy drupes (drupe). Many seeds contain an aril.

Members of Surianaceae are trees or shrubs with simple, spirally arranged leaves. The flowers are bisexual and usually radially symmetric, with five sepals and petals except in the unisexual and wind-pollinated Stylobasium, which lacks petals. The number of carpels varies from one to five. The fruits are berries, drupes, or nuts.

The three species of Quillaja, the only genus in Quillajaceae, are small, evergreen trees with bark containing considerable quantities of saponins. Leaves are spirally arranged and toothed. The terminal inflorescence contains five parted flowers usually with a well-developed nectary inserted into the hypanthium (floral cup). The flowers are rather remarkable looking with the stamens opposite the sepals borne on the outer edge of the hypanthium disk and the stamens opposite the petals borne near the base of the ovary. The five carpels of the ovary mature into follicles splitting along one side to release winged seeds.

Classification of Fabaceae

Fabaceae has traditionally been divided into three subfamilies: Caesalpinioideae, Mimosoideae, and Faboideae (or Papilionoideae), each of which have been considered a separate plant family in the past. Classifications based on molecular analyses now separate Caesalpinioideae into several lineages and recognize the tribe Cercideae as a separate and more basal group in the family. The floral types in the legume family are quite variable, with flowers ranging from regular (i.e., actinomorphic, radially symmetric) in Mimosoideae to highly irregular (i.e., zygomorphic, bilaterally symmetric) in Faboideae. The flowers of the tribes Cercideae and Caesalpinioideae are somewhat intermediate between these extremes as regards symmetry.

Cercideae is a small tropical and temperate woody group (e.g., Cercis, Bauhinia) in which the leaves are apparently simple and often bilobed. The flowers of Cercis are only superficially similar to those of Faboideae.

The subfamily Caesalpinioideae (classified as a family, Caesalpiniaceae, by some authorities) is a heterogeneous group of plants with about 160 genera and some 2,000 species. The latest classifications show that this subfamily is the most basal lineage among the legumes and the one from which the other two subfamilies evolved. In that sense it is not a true monophyletic group, and it will undoubtedly be treated taxonomically in a different way in the future. Caesalpinioideae legumes are found throughout the world but are primarily woody plants in the tropics. Their moderate secondary invasion of temperate regions is mostly by herbaceous (nonwoody) evolutionary derivatives. The presence of Gleditsia triacanthos ( honey locust) and of the related Gymnocladus dioica (Kentucky coffee tree) in temperate regions is a striking exception to this generalization, however, and they may represent more ancient and relictual lineages in the subfamily.

The subfamily Caesalpinioideae (classified as a family, Caesalpiniaceae, by some authorities) is a heterogeneous group of plants with about 160 genera and some 2,000 species. The latest classifications show that this subfamily is the most basal lineage among the legumes and the one from which the other two subfamilies evolved. In that sense it is not a true monophyletic group, and it will undoubtedly be treated taxonomically in a different way in the future. Caesalpinioideae legumes are found throughout the world but are primarily woody plants in the tropics. Their moderate secondary invasion of temperate regions is mostly by herbaceous (nonwoody) evolutionary derivatives. The presence of Gleditsia triacanthos ( honey locust) and of the related Gymnocladus dioica (Kentucky coffee tree) in temperate regions is a striking exception to this generalization, however, and they may represent more ancient and relictual lineages in the subfamily.Caesalpinioideae is more variable than the other three groups. The leaves are usually divided into leaflets (compound), or else the leaflets are again divided into leaflets (bicompound). The flowers also vary in symmetric (symmetry) form, from nearly radial to bilateral to irregular (symmetric in no plane). The sepals are usually separate and imbricate (overlapping in the bud). There are generally five separate imbricate petals, the upper one inside of the lateral petals in the bud. The 10 or fewer stamens are exposed, although not as conspicuously as in many of the members of the subfamily Mimosoideae described below. The fruit conformation is diverse. Bacterial nodulation is much less prevalent than in either of the other two subfamilies. Canavanine is not present. Many Caesalpinioideae species are prized ornamentals in the tropics, such as Delonix regia (royal poinciana), Cassia grandis (pink shower), and Bauhinia (orchid trees). Gleditsia triacanthos (honey locust) is well known in temperate regions.

The subfamily Mimosoideae (classified as a family, Mimosaceae, by some authorities) includes 82 genera and more than 3,200 species. Like Caesalpinioideae, Mimosoideae legumes are primarily woody plants of the tropics, and the few species native to temperate parts of the world are mostly herbaceous. The majority of Mimosoideae have large leaves that are divided into secondary (compound) leaflets, and in many these leaflets are again divided (bicompound) and have a feathery, sometimes fernlike appearance. A striking exception is that of most of the Australian acacias (acacia) (but not of the American kinds) mentioned above, in which the compound leaves have become modified, losing all their leaflets and appearing to be undivided, or simple. The flowers of the family are radially symmetric and are usually most easily recognized by the long stamens that extend beyond the rest of the flower. The calyx and corolla are both valvate in bud, contrasting with the usual condition in both of the other subfamilies. The petals are small and often not noticed except by close examination. Many of these plants have nodules containing the nitrogen-fixing bacterium Rhizobium on their roots.

Mimosa pudica (sensitive plant) is sometimes grown as a novelty because its leaves quickly fold up when touched. Albizia julibrissin (mimosa, or silk, tree), a widely planted ornamental in the southern United States, folds its leaves together at dusk, decreasing by at least half the amount of leaf surface exposed to the atmosphere. The movement is caused by changes in water pressure in specialized structures at the base of the petioles and leaflets.

Mimosa pudica (sensitive plant) is sometimes grown as a novelty because its leaves quickly fold up when touched. Albizia julibrissin (mimosa, or silk, tree), a widely planted ornamental in the southern United States, folds its leaves together at dusk, decreasing by at least half the amount of leaf surface exposed to the atmosphere. The movement is caused by changes in water pressure in specialized structures at the base of the petioles and leaflets.The subfamily Faboideae, also called Papilionoideae (classified as a family, Fabaceae or Papilionaceae, by some authorities), is the largest group of legumes, consisting of about 475 genera and nearly 14,000 species grouped in 14 tribes. The name of the group probably originated because of the flower's resemblance to a butterfly (Latin: papilio). It is the unique bilaterally symmetric (zygomorphic) flowers that especially characterize the group, so that thousands of species can be recognized as a member of Papilionoideae at a glance. The Lathyrus odoratus ( sweet pea) flower provides an example. It has a large petal at the top, called the banner, or standard, that develops outside of the others before the flower has opened, two lateral petals called wings, and two lower petals that are usually fused and form a keel that encloses the stamens and pistil. The whole design is adapted for pollination by insects or, in a few members, by hummingbirds. Sweet nectar, to which the insects are cued by coloured petals, is the usual pollinator attractant. Various locking and releasing devices of the keel and wing petals control pollination in diverse ways favouring (or enforcing) either outcrossing or self-pollination—e.g., Trifolium ( clover), Medicago ( alfalfa), and Lotus corniculatus ( bird's-foot trefoil). The most effective kind of obligate self-pollination, however, is that of cleistogamous flowers, which do not open and thus prevent the entry of insects. Lespedeza and many other genera of Papilionoideae legumes bear both kinds of flowers, generally on the same plant. Enforced inbreeding serves to fix and maintain successful strains; outbreeding provides evolutionary diversity that may facilitate habitat or range expansion or may serve to provide flexibility for environmental changes.

The calyx is composed of fused sepals. The stamens are 10 or fewer and are free in a few tribes but are most commonly fused at their filaments (monadelphous) or fused at all filaments but one, which remains free (diadelphous). The ovary has a single carpel and develops into various fruit types.

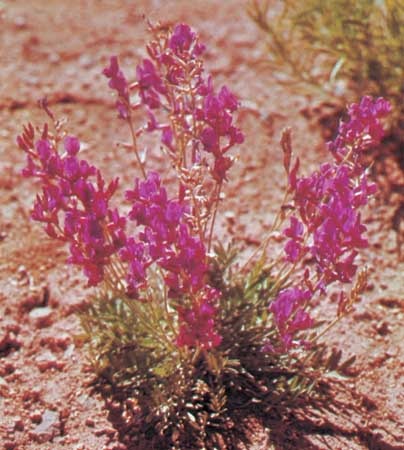

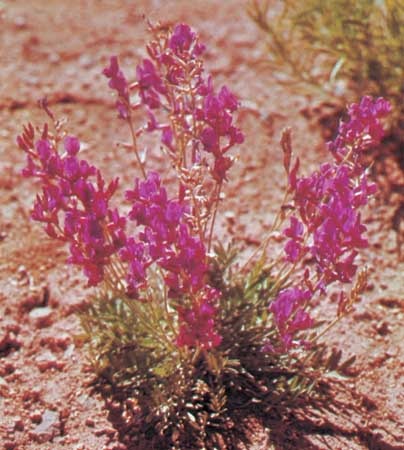

Like the other subfamilies, members of Papilionoideae have their origins in the tropics, but their occupation of the arid and temperate parts of the world, mostly as herbaceous plants, is far more extensive. In the forests, prairies, and deserts, they are among the most common plants. The largest genus of legumes, Astragalus (2,400 to 3,300 species, known as locoweed), is mainly western North American but also occurs in Eurasia, India, Africa, and South America. These temperate legumes have mostly pinnate leaves among which those with three leaflets (trifoliolate) are common—e.g., beans (bean) and soybeans (soybean). Trifoliolate leaves rarely occur in the other subfamilies. The large genus of Lupinus (lupines (lupine)) generally has 5 to 11 (occasionally up to 15) palmate leaves. The leaves of clovers (clover) are most commonly palmately trifoliolate, as are those of Baptisia. In one tribe the leaf axis terminates in a tendril, which facilitates climbing; members include the sweet pea and Vicia (vetches (vetch)). The symbiotic relationship between Rhizobium and the plant, which takes place in root nodules and “fixes” atmospheric nitrogen into compounds useful to the plant, is most strongly developed in Papilionoideae legumes.

Like the other subfamilies, members of Papilionoideae have their origins in the tropics, but their occupation of the arid and temperate parts of the world, mostly as herbaceous plants, is far more extensive. In the forests, prairies, and deserts, they are among the most common plants. The largest genus of legumes, Astragalus (2,400 to 3,300 species, known as locoweed), is mainly western North American but also occurs in Eurasia, India, Africa, and South America. These temperate legumes have mostly pinnate leaves among which those with three leaflets (trifoliolate) are common—e.g., beans (bean) and soybeans (soybean). Trifoliolate leaves rarely occur in the other subfamilies. The large genus of Lupinus (lupines (lupine)) generally has 5 to 11 (occasionally up to 15) palmate leaves. The leaves of clovers (clover) are most commonly palmately trifoliolate, as are those of Baptisia. In one tribe the leaf axis terminates in a tendril, which facilitates climbing; members include the sweet pea and Vicia (vetches (vetch)). The symbiotic relationship between Rhizobium and the plant, which takes place in root nodules and “fixes” atmospheric nitrogen into compounds useful to the plant, is most strongly developed in Papilionoideae legumes.The legumes produce many kinds of chemical substances—e.g., alkaloids (alkaloid), flavonoids (flavonoid), tannins (tannin), and the free amino acid canavanine (the latter found only in legumes). The function of those that are physiologically active (i.e., often poisonous) in animals seems usually to be that of predator defense. The medical potential (especially of the alkaloids) of some of these substances, or of their synthetic derivatives, has been extensively studied. The absence or presence and distribution of these substances in the various groups are also used in legume classification. Information about other cryptic features, such as pollen and plant anatomy, contributes to scientific knowledge of legume evolution as well.

Evolution

The origin of Fabales and its relationship to other plant families and orders are now becoming clearer. The order is closely related to a group of Rosid orders that also contain nitrogen-fixing plants: Rosales, Cucurbitales, and Fagales. Members of these orders which do fix nitrogen, however, use root-dwelling actinomycetes (actinomycete), typically Frankia, rather than Rhizobium and relatives used in legumes. There are at least six independent origins of the symbiotic relationships of Frankia and host plants. Within the order Fabales, the family Polygalaceae is most distant with the three other families, Surianaceae, Quillajaceae, and Fabaceae, possessing stipules and separate carpels. Of the latter three families, Quillajaceae and Fabaceae are most closely related and share the feature of clawed petals.

Molecular evidence confirms the hypothesis that Caesalpinioideae includes the earliest diverging lineages among the legumes. This was also the prevailing theory prior to molecular studies, based on the group's high diversity in the tropics, an extended fossil record, and the wide variation of floral and vegetative structures beyond the specializations in the other two subfamilies. The unique Rhizobium nitrogen-fixation (nitrogen fixation) symbiosis is much less developed in Caesalpinioideae than in the other groups; indeed, it seems to have originated in this subfamily. What is becoming more clear, however, is that Caesalpinioideae legumes are more diverse than previously thought and that the other two subfamilies, Mimosoideae and Papilionoideae, were derived from particular lineages among the diverse Caesalpinioideae legumes. This strengthens the idea that legumes form a single family; however, the phylogenetic relationships within the family are more complex than the former simple division into three subfamilies. A clearer picture is expected to develop in the future as further molecular analysis is obtained.

Ecological and economic importance

The unique ecological role of Fabaceae is in nitrogen fixation. nitrogen is an element of all proteins (protein) and is an essential component in both plant and animal metabolism. Although elemental nitrogen makes up about 80 percent of the atmosphere, it is not directly available to living organisms; nitrogen that can be metabolized by living organisms must be in the form of nitrates (nitrate) or ammonia compounds. Through a mutual benefit arrangement ( symbiosis) between legumes (legume) and Rhizobium bacteria, nitrogen gas (N2) is fixed into a compound and then becomes available to the biotic world. The legume plant furnishes a home and subsistence for the bacteria in root nodules. In a complex biosynthetic interaction between the host plant and the bacterium, nitrogen compounds are formed that are used by the host plant. These compounds are also available to other plants after decayed roots (and other plant parts) of the host plant have allowed these nitrogen products to be released into the soil. Animals obtain compound nitrogen by eating plants or other animals.

The unique ecological role of Fabaceae is in nitrogen fixation. nitrogen is an element of all proteins (protein) and is an essential component in both plant and animal metabolism. Although elemental nitrogen makes up about 80 percent of the atmosphere, it is not directly available to living organisms; nitrogen that can be metabolized by living organisms must be in the form of nitrates (nitrate) or ammonia compounds. Through a mutual benefit arrangement ( symbiosis) between legumes (legume) and Rhizobium bacteria, nitrogen gas (N2) is fixed into a compound and then becomes available to the biotic world. The legume plant furnishes a home and subsistence for the bacteria in root nodules. In a complex biosynthetic interaction between the host plant and the bacterium, nitrogen compounds are formed that are used by the host plant. These compounds are also available to other plants after decayed roots (and other plant parts) of the host plant have allowed these nitrogen products to be released into the soil. Animals obtain compound nitrogen by eating plants or other animals.Consequently, the vegetation of the forests, prairies, and deserts of most of the world is primarily dependent on the legume component of their vegetation and could not exist without it. Only in a few ecosystems—those that include few legume species—have alternative biological nitrogen-fixing arrangements evolved. These include symbiotic relationships between miscellaneous woody species other than legumes, and certain actinomycetes (actinomycete) or bacteria and are limited mostly to boreal evergreen forests, certain coastal areas, and acid bogs. Nitrogen fixation by free-living cyanobacteria seems to be important in aquatic ecosystems. On a worldwide scale, however, these alternate arrangements of nitrogen fixation are relatively minor compared with those supported by legumes.

Legume nitrogen fixation is of prime importance in agriculture. Before the use of synthetic fertilizers (fertilizer) in the industrial countries, the cultivation of crop plants, with the exception of rice, was dependent on legumes and plant and animal wastes (as manure) for nitrogen fertilization. A common procedure was the use of crop rotation, usually the alternation of a cash grain crop such as corn (maize) with a legume, often alfalfa (Medicago sativa), in the temperate world. Apart from the nitrogen contribution, the legume in this case furnishes animal forage ( hay or silage). Pastures or other grazing areas must have legume components, such as a clover (Trifolium), as well as a grass component.

Legume nitrogen fixation is of prime importance in agriculture. Before the use of synthetic fertilizers (fertilizer) in the industrial countries, the cultivation of crop plants, with the exception of rice, was dependent on legumes and plant and animal wastes (as manure) for nitrogen fertilization. A common procedure was the use of crop rotation, usually the alternation of a cash grain crop such as corn (maize) with a legume, often alfalfa (Medicago sativa), in the temperate world. Apart from the nitrogen contribution, the legume in this case furnishes animal forage ( hay or silage). Pastures or other grazing areas must have legume components, such as a clover (Trifolium), as well as a grass component.The 20th-century substitution of petroleum-derived synthetic nitrogen fertilizers is partly a consequence of economics in that a cash grain, such as corn or wheat, planted every year provides a higher fiscal return than alternating it with a legume crop. In addition, legume-rhizobium nitrogen fixation is inhibited when the level of nitrogen in the soil is high and is not sufficient for maximum yields of a grass crop. Therefore, in developed countries chemical fertilizers have largely replaced biological fixation in row-crop culture. On a worldwide basis, however, dependence on legumes is still preeminent. Even in the United States, when rangeland and pasture agriculture are included, it has been estimated that nitrogen production by biological fertilizers still exceeds chemical application.

Other benefits accrue from the use of legumes to maintain soil nitrogen. Weed control is facilitated by a crop sequence that alternately changes the growing environment. Such legumes as alfalfa may be harvested for forage (hay or silage) or grazed by livestock. As cover crops, legumes prevent or reduce soil erosion and may be plowed under as “green manure.” Even though starch-producing grasses such as corn are more efficient under favourable conditions in producing energy foods, grain legumes are commonly grown in the tropics because they are more successful in depleted, nitrogen-deficient soils.

Legume seeds (seed and fruit) constitute a part of the diet of nearly all humans. Their most vital role is that of supplying most of the protein in regions of high population density and in balancing the deficiencies of cereal protein (Poaceae). Except for the soybean and peanut, the order is not noted for the oil content of the seeds since most seeds have only about 10 percent oil content by weight. The legume seeds generally are highest in carbohydrate compounds, followed by protein and fat. Legumes are thus considered to be energy foods. Most legumes that are used for foods are multipurpose plants, serving for animal forage and soil improvement as well. Some, notably the soybean, are also important industrial crops. Fabaceae contains the more important crop plants, such as soybeans, beans (bean), cowpeas (cowpea) (Vigna), pigeon peas (Cajanus cajan), chick-peas (chick-pea) (Cicer arietinum), lentils (lentil) (Lens culinaris), peas (pea) (Pisum sativum), and peanuts.

Forage legumes (which concentrate their vitamins and proteins in their young growing parts) also are grown as animal feed. Their role as such is especially common in countries that can afford the luxury of meat (luxury because livestock typically yield fewer calories than the plants they are fed). Some major forage legumes of the temperate world include clovers (clover), alfalfa, bird's-foot trefoil (Lotus corniculatus), and vetches (vetch). In the tropics or arid regions, some of the important elements of the habitat are species of Glycine (soybean), Stylosanthes, and Desmodium (tick trefoil).

Forage legumes (which concentrate their vitamins and proteins in their young growing parts) also are grown as animal feed. Their role as such is especially common in countries that can afford the luxury of meat (luxury because livestock typically yield fewer calories than the plants they are fed). Some major forage legumes of the temperate world include clovers (clover), alfalfa, bird's-foot trefoil (Lotus corniculatus), and vetches (vetch). In the tropics or arid regions, some of the important elements of the habitat are species of Glycine (soybean), Stylosanthes, and Desmodium (tick trefoil).Apart from the legume plants of worldwide importance, the following are examples of locally significant legume species that are cultivated or gathered from the wild. Some would plainly have substantial potential were they subject to genetic evaluation and development through modern breeding techniques. They are still in the same stage as teosinte (the ancestor of corn) or einkorn and emmer (the ancestors of the modern varieties of cultivated wheats) in yield and utilization potential.

Notable among the locally useful plants of the legume family is Vigna subterranea (Bambara groundnut), a leguminous plant that develops underground fruits in the arid lands of Africa. Important too are the seeds of Bauhinia esculenta; they are gathered for the high-protein tubers and seeds. Vigna aconitifolia (moth bean) and V. umbellata (rice bean) are much used in the tropics for forage and soil improvement, and their seeds are palatable and rich in protein. Psophocarpus tetragonolobus (winged bean) is collected in Southeast Asia for the edible fruits and protein-rich tubers. Pachyrhizus (yam bean (jícama)) is a high-yield root crop of Central America.

Various forms of leucaena (such as Leucaena leucocephala) have been developed for animal forage, firewood, and construction, as well as for the high production of nitrogen that enriches impoverished soils, especially in the Asiatic tropics. Other important plants are acacia, used for animal food (both pods and leaf forage), for soil improvement and revegetation, and as a source of tannin and pulpwood; Cordeauxia edulis (yeheb), an uncultivated desert shrub of North Africa that has been so extensively exploited for food (seeds) that it is in danger of extinction; Ceratonia siliqua ( carob), a Mediterranean plant whose fruits are used as animal and human food and in the manufacture of industrial gums; and Tamarindus indica ( tamarind) of Africa, now primarily grown in India, which has food and medicinal uses and is also used as an industrial gum.

Various forms of leucaena (such as Leucaena leucocephala) have been developed for animal forage, firewood, and construction, as well as for the high production of nitrogen that enriches impoverished soils, especially in the Asiatic tropics. Other important plants are acacia, used for animal food (both pods and leaf forage), for soil improvement and revegetation, and as a source of tannin and pulpwood; Cordeauxia edulis (yeheb), an uncultivated desert shrub of North Africa that has been so extensively exploited for food (seeds) that it is in danger of extinction; Ceratonia siliqua ( carob), a Mediterranean plant whose fruits are used as animal and human food and in the manufacture of industrial gums; and Tamarindus indica ( tamarind) of Africa, now primarily grown in India, which has food and medicinal uses and is also used as an industrial gum. The soybean is a bushy annual whose seeds are an important source of oil and protein. An edible oil pressed from the seeds is used to make margarine and as a stabilizing agent in the processing of food and the manufacture of cosmetics and pharmaceuticals. The oil is employed in such industrial products as paint, varnish, printing ink, soaps, insecticides, and disinfectants. Oil cakes pressed from the seeds are used as protein concentrate in the mixed-feeds industry. The soybean is a good source of vitamin B (vitamin B complex) and is dried to produce soy milk, which is used in infant formulas. Fermented pods are used in making soy sauce, a flavouring common in Asian cooking.

The soybean is a bushy annual whose seeds are an important source of oil and protein. An edible oil pressed from the seeds is used to make margarine and as a stabilizing agent in the processing of food and the manufacture of cosmetics and pharmaceuticals. The oil is employed in such industrial products as paint, varnish, printing ink, soaps, insecticides, and disinfectants. Oil cakes pressed from the seeds are used as protein concentrate in the mixed-feeds industry. The soybean is a good source of vitamin B (vitamin B complex) and is dried to produce soy milk, which is used in infant formulas. Fermented pods are used in making soy sauce, a flavouring common in Asian cooking. The peanut, a native of South America, is high in vitamin B complex, proteins, and minerals. The peanut is eaten raw or roasted or is processed into peanut butter. An edible oil is pressed from the seed and is used as a cooking oil and in processing margarine, soap, and lubricants. The oil also is employed by the pharmaceutical industry in making medications. Pressed oil cake is fed to livestock. Peanuts are commercially grown in the United States, Asia, Africa, and Central and South America.

The peanut, a native of South America, is high in vitamin B complex, proteins, and minerals. The peanut is eaten raw or roasted or is processed into peanut butter. An edible oil is pressed from the seed and is used as a cooking oil and in processing margarine, soap, and lubricants. The oil also is employed by the pharmaceutical industry in making medications. Pressed oil cake is fed to livestock. Peanuts are commercially grown in the United States, Asia, Africa, and Central and South America.Legumes in general are used to revitalize nutrient-depleted soils, especially abandoned or abused agricultural and grazing lands. A more stringent revegetational challenge is that following strip-mining (strip mining). Generally speaking, native legumes are common in these habitats because they are better able to thrive in nitrogen-poor soils than other plants.

As mentioned above, the legumes produce secondary compounds of an irritating or poisonous (poison) nature that provide protection against predators. Some of these secondary compounds are being studied for their pharmacological potential. They are found in the leaves and fruiting parts and include flavonoids (flavonoid), alkaloids (alkaloid), terpenoids, nonprotein amino acids (amino acid), and others. Some of these—for example, the amino acid canavanine—may comprise up to 5 percent of the dry weight of seeds. The chemical compound rotenone, which is toxic to a number of organisms, is sufficiently abundant in the roots and stems of certain species belonging to the Papilionoideae that primitive peoples often used these plants to poison fish. More recently it has been shown that serious bone and neural diseases afflicting humans (e.g., lathyrism) and livestock may be caused by the ingestion of unusually large amounts of certain free amino acids (amino acid). In sheep, ingestion of large quantities of the amino acid mimosine, found in Leucaena glauca and some other species of the Mimosoideae, apparently halts the growth of hair or wool, and in certain cases the fleece itself has been observed to shed. A wide variety of alkaloids (alkaloid) are found in the order, most of them restricted to Fabaceae, however. Some alkaloids occur in sufficient concentration in range plants to be poisonous to livestock, especially in species belonging to the large genus Astragalus. Species of Astragalus are commonly referred to as locoweed in North America because, following excessive consumption of these plants, cattle seem to become unmanageable and “go crazy” or “loco.” Astragalus is poisonous in any of three ways: by promoting selenium accumulation, through locoine, and through several nitrogen-containing toxins. In the early 20th century, several African species of Crotalaria were brought to the United States for use as soil-improvement plants. Their poisonous qualities were discovered in connection with animal stock loss, and development was then halted, but several persist as common noxious weeds.

As mentioned above, the legumes produce secondary compounds of an irritating or poisonous (poison) nature that provide protection against predators. Some of these secondary compounds are being studied for their pharmacological potential. They are found in the leaves and fruiting parts and include flavonoids (flavonoid), alkaloids (alkaloid), terpenoids, nonprotein amino acids (amino acid), and others. Some of these—for example, the amino acid canavanine—may comprise up to 5 percent of the dry weight of seeds. The chemical compound rotenone, which is toxic to a number of organisms, is sufficiently abundant in the roots and stems of certain species belonging to the Papilionoideae that primitive peoples often used these plants to poison fish. More recently it has been shown that serious bone and neural diseases afflicting humans (e.g., lathyrism) and livestock may be caused by the ingestion of unusually large amounts of certain free amino acids (amino acid). In sheep, ingestion of large quantities of the amino acid mimosine, found in Leucaena glauca and some other species of the Mimosoideae, apparently halts the growth of hair or wool, and in certain cases the fleece itself has been observed to shed. A wide variety of alkaloids (alkaloid) are found in the order, most of them restricted to Fabaceae, however. Some alkaloids occur in sufficient concentration in range plants to be poisonous to livestock, especially in species belonging to the large genus Astragalus. Species of Astragalus are commonly referred to as locoweed in North America because, following excessive consumption of these plants, cattle seem to become unmanageable and “go crazy” or “loco.” Astragalus is poisonous in any of three ways: by promoting selenium accumulation, through locoine, and through several nitrogen-containing toxins. In the early 20th century, several African species of Crotalaria were brought to the United States for use as soil-improvement plants. Their poisonous qualities were discovered in connection with animal stock loss, and development was then halted, but several persist as common noxious weeds.An interesting biochemical component of the legume seed is phytohemagglutinin, a large protein molecule that is specific in its capacity to agglutinate certain human blood types. Approximately 60 percent of the several thousand seeds belonging to this order tested to date contain the compound. Phytohemagglutinin is particularly abundant in the common bean and has been extracted in a relatively pure state on a commercial scale from species belonging to this genus. In addition to its agglutination properties, the compound has been of interest because of its other biological effects. It is toxic to rats, inactivates some human tumor cells, and has beneficial effects in the treatment of aplastic anemia, the shortage of blood cells in humans due to the destruction of blood-forming tissues.

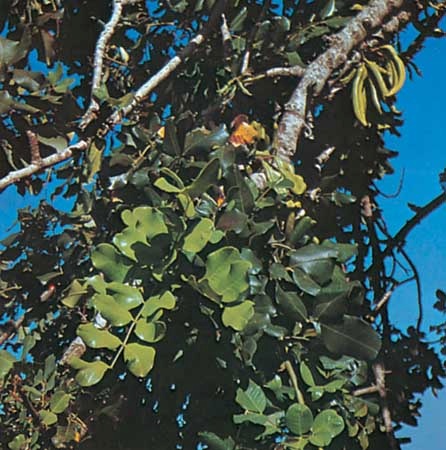

The subfamilies Caesalpinioideae and Mimosoideae do not contain many food crops and are perhaps best known for their shade and ornamental species, such as Cercis siliquastrum (the Judas tree, or redbud), Bauhinia bartlettii (orchid tree), and Acacia farnesiana (sweet acacia), although some of the more rapid-growing weedy species—for example, Leucaena leucocephala (white popinac) and Albizia species—are widely employed as green manure and fodder crops. Acacia species are used extensively in the production of gum exudates and wood, especially in South Africa and Australia, where the species are known as wattle trees.

The subfamilies Caesalpinioideae and Mimosoideae do not contain many food crops and are perhaps best known for their shade and ornamental species, such as Cercis siliquastrum (the Judas tree, or redbud), Bauhinia bartlettii (orchid tree), and Acacia farnesiana (sweet acacia), although some of the more rapid-growing weedy species—for example, Leucaena leucocephala (white popinac) and Albizia species—are widely employed as green manure and fodder crops. Acacia species are used extensively in the production of gum exudates and wood, especially in South Africa and Australia, where the species are known as wattle trees.- López, Luis Carlos

- López Mateos, Adolfo

- López Michelsen, Alfonso

- López Obrador, Andrés Manuel

- López Portillo, José

- López Rega, José

- López Velarde, Ramón

- López y Fuentes, Gregorio

- Löffler, Friedrich August Johannes

- Lönnrot, Elias

- Lúcio Costa

- Lübeck

- Lübke, Heinrich

- Lü Buwei

- Lüdenscheid

- Lüderitz

- Lüdke, Bruno

- Lüliang Mountains

- Lüneburg

- Lüneburg Heath

- Lünen

- lü pipes

- lüshi

- Lüshun

- Lü Tung-pin