flea

insect

Introduction

any of a group of bloodsucking insects that are important carriers of disease and can be serious pests. Fleas are parasites (parasitism) that live on the exterior of the host (i.e., are ectoparasitic). As the chief agent transmitting the Black Death (bubonic plague) in the Middle Ages, they were an essential link in the chain of events that resulted in the death of a quarter of the population of Europe.

any of a group of bloodsucking insects that are important carriers of disease and can be serious pests. Fleas are parasites (parasitism) that live on the exterior of the host (i.e., are ectoparasitic). As the chief agent transmitting the Black Death (bubonic plague) in the Middle Ages, they were an essential link in the chain of events that resulted in the death of a quarter of the population of Europe.General features

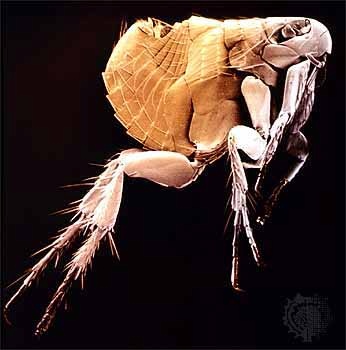

Fleas are small, wingless insects with a tough cuticle bearing many bristles and frequently combs (ctenidia) of broad, flattened spines. The adult flea varies from about 0.1 to 1 cm (0.039 to 0.39 inch) in length and feeds exclusively on the blood of mammals (including man) and birds. With about 2,000 species and subspecies known, the order is still a small one compared with many other groups of insects. However, it is widely distributed with some—such as the rat flea and the mouse flea—having been carried all over the world by man. Native species of fleas are found in polar, temperate, and tropical regions.

Fleas are small, wingless insects with a tough cuticle bearing many bristles and frequently combs (ctenidia) of broad, flattened spines. The adult flea varies from about 0.1 to 1 cm (0.039 to 0.39 inch) in length and feeds exclusively on the blood of mammals (including man) and birds. With about 2,000 species and subspecies known, the order is still a small one compared with many other groups of insects. However, it is widely distributed with some—such as the rat flea and the mouse flea—having been carried all over the world by man. Native species of fleas are found in polar, temperate, and tropical regions.Importance

Infestation by fleas may cause severe inflammation of the skin and intense itching. Although many animals acquire partial immunity after constant or repeated attacks, individuals (especially man) can occasionally become sensitized after exposure and develop allergies. Species that attack man and livestock include the cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis), the so-called human flea (Pulex irritans), the dog flea (Ctenocephalides canis), the sticktight flea (Echidnophaga gallinacea), and the jigger, or chigoe, flea (Tunga penetrans). Poultry may be parasitized by the European chicken flea (Ceratophyllus gallinae) and, in the U.S., by the western chicken flea (Ceratophyllus niger).

Certain fleas that feed primarily on rodents or birds sometimes attack man, particularly in the absence of their usual host. When rats (rat) are dying of bubonic plague, their hungry fleas, themselves infected with plague bacilli and seeking food elsewhere, can transmit the disease to man, especially in buildings heavily infested with rats. The Oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis) is the most efficient carrier of plague, but other species of fleas (e.g., Nosopsyllus fasciatus, Xenopsylla brasiliensis, Pulex irritans) can also transmit the disease to man. Although there are occasional cases of plague in tropical and some temperate regions, the disease in man can be controlled by early diagnosis and antibiotics. Plague (sylvatic plague) is a widespread disease in hundreds of species of wild rodents throughout the world and is maintained in those populations by fleas that parasitize these animals. More than 100 species of fleas are known to be able to be infected by the plague bacillus, and an additional 10 species are implicated as carriers of the classic type of urban plague. (See infection (infectious disease).)

Fleas, particularly Xenopsylla cheopis, are believed to be the principal carriers of murine typhus, a rickettsial disease of man. As in plague, rats and mice are the sources of infection. Fleas are considered important in the maintenance and spread of many locally restricted infections among rodents and other mammals, including tularemia and Russian spring-summer encephalitis. Fleas transmit myxomatosis, a viral disease of rabbits, which is used deliberately to control rabbits in areas where they are severe pests (e.g., in Australia). Fleas are probable carriers of a filarial worm of dogs and serve as the intermediate host of a common tapeworm (Dipylidium caninum) of dogs and cats, and occasionally children. If heavily infested, animals can suffer severe damage or be killed by the effects of flea bites and the resultant loss of blood. Fleas are subject to parasitism by external mites, internal nematode worms, and bacterial, fungal, and protozoan infections.

The female jigger, or chigoe, flea (not to be confused with “chigger,” a larval mite) burrows into the skin of its host, generally on the feet, and lives within a cyst that forms around it. Intense itching accompanies the development and enlargement of the cyst as the abdomen of the pregnant flea swells to the size of a pea; secondary infections may constitute serious complications.

Natural history

Life cycle

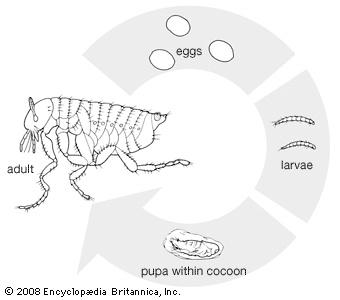

Details of the life cycle are available for only a few species. The four life stages are the egg, larva, pupa, and adult. Pearly white, oval eggs are deposited on the body of, or in the nest or habitat of, the host animal. The larva is small and legless and feeds on organic debris, such as dried excrement, dried bits of skin, dead mites, or dried blood found in the host's nest. The adult fleas pass freshly imbibed blood rapidly through their gut to produce fecal matter for the nourishment of their offspring, which is essential to the successful metamorphosis of certain species of flea larvae. After three (exceptionally, two) molts, the larva spins a silk cocoon that includes debris from the nest and enters the pupal stage. The pupa emerges as an adult some days or months later. Some species can enter an arrested state of development at the end of the pupal stage and will not emerge as an adult until a host is present. Depending upon the species or environmental conditions, the time required for a complete life cycle varies from two weeks to several months. The life-span of the adult flea varies from a few weeks (e.g., Echidnophaga gallinacea) to a year or more (Pulex irritans). The life cycle of the European rabbit flea (Spilopsyllus cuniculi) and its host are perfectly synchronized. The sexual development of male and female fleas is under the direct control of the rabbit's sex hormones. Thus, the eggs of the female flea mature successfully only if she is feeding on a pregnant doe rabbit. When the young rabbits are born, both flea sexes mature and leave the parturient doe for the nestlings and the nest, where they copulate and lay their eggs, thus assuring the flea larvae a suitable habitat for development. If the sex hormones of the female rabbit are controlled artificially by the administration of synthetic progestins (contraceptives), the sexual development of the female flea is also arrested. Although no similar case is yet known among other species of fleas, it has been recorded that rat fleas are less fertile if fed on baby mice than on their parents and that the mouse flea (Leptopsylla segnis) is more prolific if reared on family units rather than on individual adult mice. It seems likely, therefore, that the influence of the hosts' hormones is more widespread than had been suspected.

Details of the life cycle are available for only a few species. The four life stages are the egg, larva, pupa, and adult. Pearly white, oval eggs are deposited on the body of, or in the nest or habitat of, the host animal. The larva is small and legless and feeds on organic debris, such as dried excrement, dried bits of skin, dead mites, or dried blood found in the host's nest. The adult fleas pass freshly imbibed blood rapidly through their gut to produce fecal matter for the nourishment of their offspring, which is essential to the successful metamorphosis of certain species of flea larvae. After three (exceptionally, two) molts, the larva spins a silk cocoon that includes debris from the nest and enters the pupal stage. The pupa emerges as an adult some days or months later. Some species can enter an arrested state of development at the end of the pupal stage and will not emerge as an adult until a host is present. Depending upon the species or environmental conditions, the time required for a complete life cycle varies from two weeks to several months. The life-span of the adult flea varies from a few weeks (e.g., Echidnophaga gallinacea) to a year or more (Pulex irritans). The life cycle of the European rabbit flea (Spilopsyllus cuniculi) and its host are perfectly synchronized. The sexual development of male and female fleas is under the direct control of the rabbit's sex hormones. Thus, the eggs of the female flea mature successfully only if she is feeding on a pregnant doe rabbit. When the young rabbits are born, both flea sexes mature and leave the parturient doe for the nestlings and the nest, where they copulate and lay their eggs, thus assuring the flea larvae a suitable habitat for development. If the sex hormones of the female rabbit are controlled artificially by the administration of synthetic progestins (contraceptives), the sexual development of the female flea is also arrested. Although no similar case is yet known among other species of fleas, it has been recorded that rat fleas are less fertile if fed on baby mice than on their parents and that the mouse flea (Leptopsylla segnis) is more prolific if reared on family units rather than on individual adult mice. It seems likely, therefore, that the influence of the hosts' hormones is more widespread than had been suspected.Parasitism

Some fleas (e.g., shrew fleas and rabbit fleas) are highly host specific, whereas other species parasitize a variety of mammals. The cat flea infects not only the domestic cat but dogs, foxes, civets, mongooses, opossums, leopards, and other mammals, including man, if its regular hosts are not available. Related mammals tend to be parasitized by fleas that are themselves related. Thus the rabbitlike pikas (Ochotona) living in the Rocky Mountains are infested with two peculiar genera of fleas that occur also on pikas in the mountains of Asia, indicating a close phylogenetic relationship between these geographically separated hosts. Bird fleas have adapted themselves in relatively recent times to their avian hosts. These share several common features, one of the most obvious of which is an increase in the number of comb spines on the upper surface of the thorax that serve to anchor them within the feathers.

It is interesting that monkeys and apes do not harbour fleas, nor do horses or the majority of ungulates. The most heavily parasitized group of mammals are the rodents (e.g., rats, mice, squirrels). Their habit of nest building in holes favours development of flea larvae. Animals with no permanent home tend to have fewer fleas.

Although both flea sexes feed avidly and repeatedly on blood (a single male exception never feeds), they survive for various periods away from the host. The rabbit flea, for example, can live for nine months at temperatures around the freezing point without feeding.

Form and function

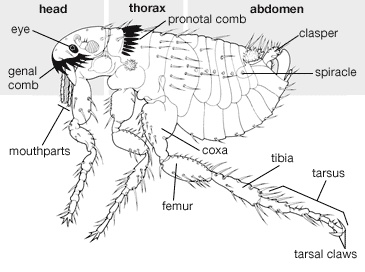

Anatomically, adult fleas are a rather uniform but distinctive group, with many interesting modifications and few obvious links with other orders. The compressed body enables them to move swiftly through hairs or feathers of the host, while the backwardly projecting spines or combs serve to anchor them within fur, hair, or feathers. The mouthparts are modified for sucking blood and include barbed stylets that aid both in penetration of the flea into the host skin and in attachment of species that spend long periods fixed to the host (e.g., the sticktight fleas). Generally fleas that live on diurnal hosts have well-developed eyes, whereas species that parasitize subterranean hosts (e.g., moles) or nocturnal animals (e.g., bats) have poorly developed eyes or none at all. The most impressive adaptations are highly developed jumping legs and the powerful muscles that control them. During their evolution, fleas, like the majority of parasitic insects, lost their wings. However, certain parts of the flight mechanism have been retained and incorporated in the jumping mechanism. Because fleas are able to leap horizontal or vertical distances 200 times their body length and to develop an acceleration of 200 gravities, they have been described as insects that fly with their legs. Certain species that live in nests high above the ground or in other unusual habitats crawl rather than jump. An incidental use of the unusual strength of fleas is in “flea circuses” in which they pull miniature carts and perform other feats.

Anatomically, adult fleas are a rather uniform but distinctive group, with many interesting modifications and few obvious links with other orders. The compressed body enables them to move swiftly through hairs or feathers of the host, while the backwardly projecting spines or combs serve to anchor them within fur, hair, or feathers. The mouthparts are modified for sucking blood and include barbed stylets that aid both in penetration of the flea into the host skin and in attachment of species that spend long periods fixed to the host (e.g., the sticktight fleas). Generally fleas that live on diurnal hosts have well-developed eyes, whereas species that parasitize subterranean hosts (e.g., moles) or nocturnal animals (e.g., bats) have poorly developed eyes or none at all. The most impressive adaptations are highly developed jumping legs and the powerful muscles that control them. During their evolution, fleas, like the majority of parasitic insects, lost their wings. However, certain parts of the flight mechanism have been retained and incorporated in the jumping mechanism. Because fleas are able to leap horizontal or vertical distances 200 times their body length and to develop an acceleration of 200 gravities, they have been described as insects that fly with their legs. Certain species that live in nests high above the ground or in other unusual habitats crawl rather than jump. An incidental use of the unusual strength of fleas is in “flea circuses” in which they pull miniature carts and perform other feats.Control

In controlling fleas it is best to treat simultaneously both the host nest or bedding area, which is the breeding site of fleas, and the infested host, since the larval and pupal stages usually develop away from the host's body. For infested animals a commercial dust, spray, dip, or aerosol containing an insecticide or growth regulator is used. However, in some regions, fleas have become resistant to some insecticides, and new materials are required. For the control of larval and adult fleas away from the host, insecticides or growth regulators may be applied to the pens and haunts of the affected animals. Repellents may be effective in preventing attack by fleas.

Evolution, paleontology, and classification

The Siphonaptera form a small group of insects that are probably descended from an ancestor of the Mecoptera (scorpionfly) (scorpionflies), with which they share certain characteristics. Both groups have a spined gizzard (proventriculus), sexual differences in the number of ganglia in the ventral nerve cord, six rectal glands, and a simple type of ovary. The males have a similar type of spermatozoon, unique in the phylum Arthropoda, in which a motile flagellum, or tail, lacking the outer ring of nine tubules, is deployed around the mitochondria (cell organelles). A fossil flea, discovered in Australia, is claimed to be 200,000,000 years old. Two other known fossil fleas come from the Baltic amber (Oligocene) and closely resemble “modern” fleas.

Distinguishing taxonomic features

Although taxonomic separation of these groups rests upon a combination of superficially trivial morphological characteristics, they do reflect the fundamental differences between the groups. At the family or generic levels, classification is based principally upon shape of head and thorax, arrangement of combs, modifications of the male copulatory organ and female reproductive organs, general chaetotaxy (arrangement of bristles), and other characteristics.

Annotated classification

Fleas of today can be divided into four superfamilies: the Pulicoidea, Malacopsylloidea, Ceratophylloidea, and Vermipsylloidea. The Pulicoidea are generally adapted more to life on the host's body than are the latter three, which spend more time in the nest.

Order Siphonaptera (fleas)

Small, wingless, laterally compressed insects; adults ectoparasitic on warm-blooded vertebrates; eyes present or lacking; antennae short and stout, reposing in grooves; mouthparts adapted to piercing and sucking, maxillary and labial palps present; thoracic segments free; legs with large coxae, tarsi five-segmented; larvae elongated, legless, caterpillar-like; pupae with appendages free, enclosed in cocoons.

Superfamily Pulicoidea

Includes cat and dog fleas, oriental rat flea, sticktight and human fleas, chigoe fleas, and fleas of birds and rabbits. Outer internal ridge of midcoxa of leg absent; mesonotum (dorsal sclerite of mesothorax) without pseudosetae under collar; metepimeron extending far upward, with first abdominal spiracle placed above the metepisternum; metanotum (dorsal sclerite of metathorax) and abdominal terga (dorsal surface) without apical spines or spinelets; spiracles circular; abdominal terga (segments II-VII) with, at most, one row of bristles; no bristles above spiracle of terga VIII; sensillium with either 8 or 14 pits each side; hind tibia of leg without an apical tooth outside; one family Pulicidae with genera Pulex, Xenopsylla, Tunga, and others.

Superfamily Malacopsylloidea

All fleas in this superfamily are found on rodents. Rod of the lateral sclerites of the mesothorax (mesopleural rod) not forked; anterior tentorial arm present in head; no genal combs (spines on the anteroventral border of head) or pronotal combs (spines on the dorsal sclerite of the prothorax); ventral margin of pronotum never bilobed; fifth tarsal segment of leg always with four pairs of bristles (Neotropical region and extreme south Nearctic); two families, Malacopsyllidae and Rhopalopsyllidae.

Superfamily Ceratophylloidea

Fleas in this superfamily are found on rodents and bats. All fleas that do not possess combinations of characters listed in the other three superfamilies are included with the Ceratophylloidea, 12 families are included.

Superfamily Vermipsylloidea

Fleas of carnivores. This contains the single family Vermipsyllidae. No combs, marginal spinelets, antepygideal bristles, or bristles on the inner side of hind coxae. Females without an anal stylet.

Critical appraisal

There is general agreement among flea specialists regarding the basic classification of the order, but it is probable that the family Hystrichopsyllidae will be accorded the rank of a superfamily.

Additional Reading

G.P. Holland, “The Siphonaptera of Canada,” Tech. Bull. Dep. Agric. Can. 70 (1949), the best work on identification, affinities and host relations of relevant North American fauna; “Evolution, Classification and Host-Relations of Siphonaptera,” A. Rev. Ent., 9:123–146 (1964), a critical review of the literature; G.H.E. Hopkins and M. Rothschild, An Illustrated Catalogue of the Rothschild Collection of Fleas (Siphonaptera) in the British Museum (Natural History), 5 vol. (1953–71), indispensable for global identification and general morphology of families treated to date; W.L. Jellison, “Fleas and Disease,” A. Rev. Ent., 4:389–414 (1959), a summary of the medical importance of fleas; P.T. Johnson, “A Classification of the Siphonaptera of South America with Descriptions of New Species,” Mem. Ent. Soc. Wash., 5:1–299 (1957), sole opus on South American fleas, well prepared and well illustrated; M. Rothschild, “Fleas,” Sci. Am. 213:44–53 (Dec. 1965), an account of interesting aspects of the biology and behaviour of fleas; “The Rabbit Flea and Hormones,” in The Biology of Sex, ed. by A. Allison, pp. 189–199 (1967), a review of findings on hormonal interrelationships of the rabbit flea and its host, and with T. Clay, Fleas, Flukes and Cuckoos, 3rd ed. (1957), information on bionomics and habits of bird fleas and other bird parasites; R. Traub, Siphonaptera from Central America and Mexico (1950), includes generic revisions and the first study on comparative anatomy of the aedeagus of fleas; United States Department of Agriculture, “Fleas—How to Control Them,” Leaflet No. 392 (n.d.), one of a series of pamphlets on methods of control; Allan H. Benton, An Atlas of the Fleas of the Eastern United States (1980).

- Ellen Spencer Mussey

- Ellen Swallow Richards

- Ellen Taaffe Zwilich

- Ellen Terry

- Ellen Wilson

- Ellery Queen

- Ellesmere Island

- Ellesmere, Lake

- Ellesmere Port and Neston

- Ellet, Charles

- Ellet, Elizabeth Fries Lummis

- Ellington, Duke

- Elliot Lake

- Elliotson, John

- Elliott Carter

- Elliott Coues

- Elliott, Denholm

- Elliott, Harriet Wiseman

- timber framing

- Timberlake, Justin

- timberline

- timbre

- Timbuktu

- Tim Duncan

- Time