Virginia

Minnesota, United States

city, St. Louis county, northeastern Minnesota, U.S. It lies in the Mesabi Range, about 60 miles (95 km) northwest of Duluth. Iron ore was discovered in 1890 by Leonidas Merritt at the site of the nearby city of Mountain Iron. Two years later ore was found at the site of Virginia, which was then laid out as a mining centre and named for the home state of an area lumberman. The city burned down in both 1893 and 1900 and was subsequently rebuilt. Lumbering soon became a major industry as well, with Virginia being the site of the world's largest white-pine mill from 1909 to 1929. In the early 1980s the mining industry suffered economic setbacks, but it remains the basis of the city's economy. Although hematite iron-ore reserves diminished, taconite is now mined. Virginia is also the area's retail hub, and tourism contributes to the local economy. The city is home to a community and technical college campus. A popular event is the Land of the Loon Ethnic Arts and Crafts Festival, which is held every June. The Mineview in the Sky Overlook offers views of the area's deepest open-pit mine. Superior National Forest is north and east of the city, and a large ski and golf resort is several miles east. Inc. village, 1892; city, 1895. Pop. (1990) 9,410; (2000) 9,157.

city, St. Louis county, northeastern Minnesota, U.S. It lies in the Mesabi Range, about 60 miles (95 km) northwest of Duluth. Iron ore was discovered in 1890 by Leonidas Merritt at the site of the nearby city of Mountain Iron. Two years later ore was found at the site of Virginia, which was then laid out as a mining centre and named for the home state of an area lumberman. The city burned down in both 1893 and 1900 and was subsequently rebuilt. Lumbering soon became a major industry as well, with Virginia being the site of the world's largest white-pine mill from 1909 to 1929. In the early 1980s the mining industry suffered economic setbacks, but it remains the basis of the city's economy. Although hematite iron-ore reserves diminished, taconite is now mined. Virginia is also the area's retail hub, and tourism contributes to the local economy. The city is home to a community and technical college campus. A popular event is the Land of the Loon Ethnic Arts and Crafts Festival, which is held every June. The Mineview in the Sky Overlook offers views of the area's deepest open-pit mine. Superior National Forest is north and east of the city, and a large ski and golf resort is several miles east. Inc. village, 1892; city, 1895. Pop. (1990) 9,410; (2000) 9,157.South Africa

town and gold-mining centre, north-central Free State province, South Africa, in one of the world's richest goldfields. Virginia was a former whistle stop (named, 1892) on the line between Johannesburg and Cape Town. A modern, well-planned town, it was founded in 1954, after gold was discovered in the vicinity. Mining, gold-extraction plants, and processing plants recovering uranium and sulfuric acid as a by-product from gold ore form the basis of the economy. Pop. (2001) 21,189.

state, United States

Introduction

Virginia, flag of

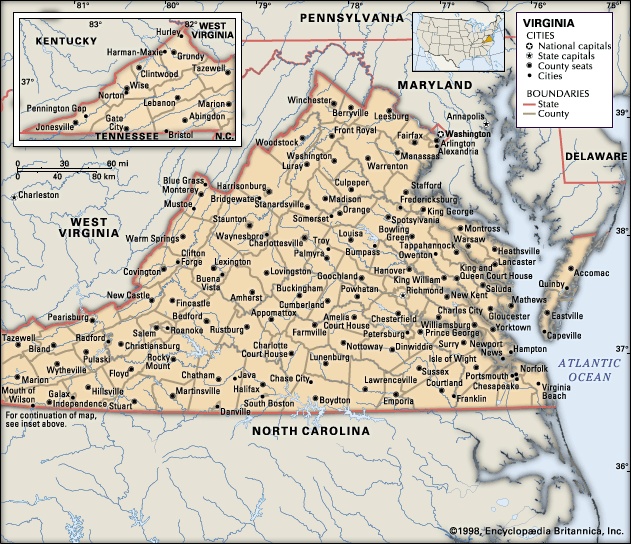

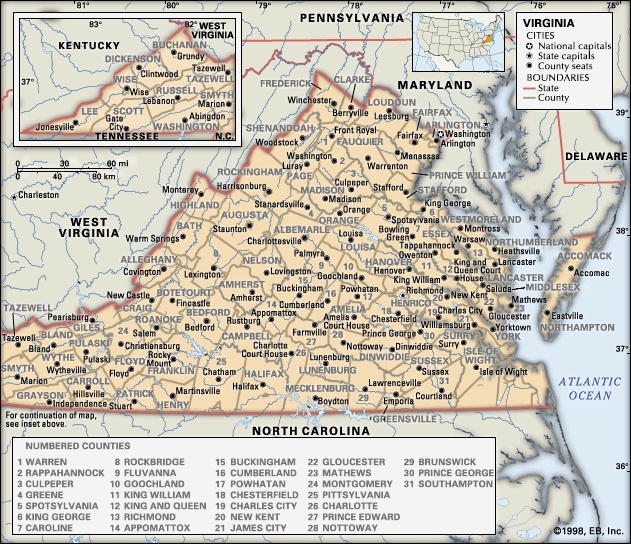

constituent state of the United States of America, one of the original 13 colonies. It is bordered by Maryland to the northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, North Carolina and Tennessee to the south, Kentucky to the west, and West Virginia to the northwest. The state capital is Richmond.

constituent state of the United States of America, one of the original 13 colonies. It is bordered by Maryland to the northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, North Carolina and Tennessee to the south, Kentucky to the west, and West Virginia to the northwest. The state capital is Richmond.

constituent state of the United States of America, one of the original 13 colonies. It is bordered by Maryland to the northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, North Carolina and Tennessee to the south, Kentucky to the west, and West Virginia to the northwest. The state capital is Richmond.

constituent state of the United States of America, one of the original 13 colonies. It is bordered by Maryland to the northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, North Carolina and Tennessee to the south, Kentucky to the west, and West Virginia to the northwest. The state capital is Richmond.Virginia was nicknamed the Old Dominion for its loyalty to the exiled Charles II of England during the Puritan (Puritanism) Commonwealth and Protectorate (1653–59). It has one of the longest continuous histories among the American states, dating from the settlement of Jamestown (Jamestown Colony) in the early 17th century. It was named for Elizabeth I, the Virgin Queen, and under its original charter was granted most of the lands stretching westward from the Atlantic seaboard settlements to the Mississippi River and beyond—territories yet unexplored by Europeans. The contributions of such Virginians as George Washington (Washington, George), Thomas Jefferson (Jefferson, Thomas), and James Madison (Madison, James) were crucial in the formation of the United States, and in the early decades of the republic the state was known as the Birthplace of Presidents.

Although during the American Civil War (1861–65) Richmond served as the capital of the Confederacy (Confederate States of America) and Virginian Robert E. Lee (Lee, Robert E.) and other generals led Confederate forces, the state developed in the 20th century into a bridge state between the North (North, the) and the South (South, the). By the early 21st century Virginia was among the most prosperous states in the South and in the country as a whole. Its northern counties reflect the cosmopolitan character of the country's capital, Washington, D.C. (Washington), which lies across the Potomac River to the north. Other areas of the state retain the tinge of conservatism developed over centuries of agricultural life and through aristocratic traditions that made the term a Virginia gentleman synonymous with gentility and refinement.

History and nature make Virginia a leading tourist centre. Within its borders lie many important historical monuments. They include colonial restorations and reconstructions, such as those at Williamsburg; the homes of Washington ( Mount Vernon), Jefferson ( Monticello), and other noted Virginians; and many of the battlefields of the American Revolution and Civil War. Although it is increasingly an industrialized and urbanized state, much of Virginia's land remains under forest cover as it descends from the mountains and valleys in the west to the beaches of the Atlantic shore. Area 40,600 square miles (105,154 square km). Pop. (2000) 7,078,515; (2006 est.) 7,642,884.

History and nature make Virginia a leading tourist centre. Within its borders lie many important historical monuments. They include colonial restorations and reconstructions, such as those at Williamsburg; the homes of Washington ( Mount Vernon), Jefferson ( Monticello), and other noted Virginians; and many of the battlefields of the American Revolution and Civil War. Although it is increasingly an industrialized and urbanized state, much of Virginia's land remains under forest cover as it descends from the mountains and valleys in the west to the beaches of the Atlantic shore. Area 40,600 square miles (105,154 square km). Pop. (2000) 7,078,515; (2006 est.) 7,642,884.Land

Relief

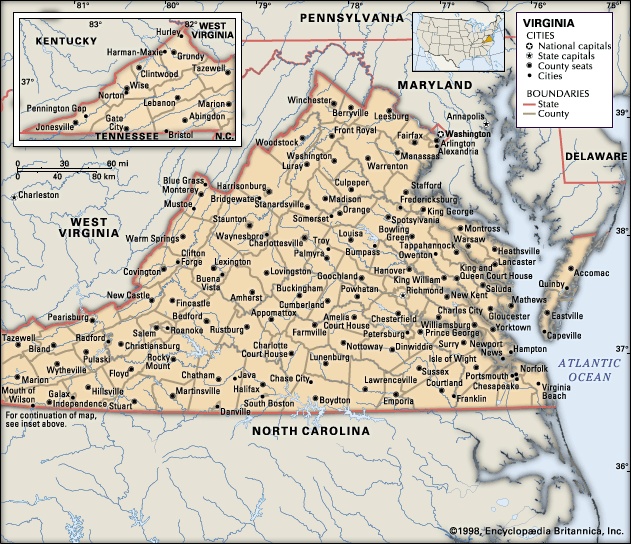

Western Virginia comprises three physiographically defined mountain provinces. From west to east, the first of these is the Appalachian Plateau, the smallest of the provinces, located in the southwestern tip of the state. The next two provinces run from northeast to southwest, generally paralleling the state's western boundary. The Valley and Ridge province consists of linear ridges in its western segment and the Great Appalachian Valley (also known as the Great Valley) in its eastern region. The Blue Ridge province is mostly a region of rugged mountains, part of a range stretching southwestward from Pennsylvania to South Carolina. The state's highest point, Mount Rogers (Rogers, Mount), at an elevation of 5,729 feet (1,746 metres), lies in the Blue Ridge area.

Western Virginia comprises three physiographically defined mountain provinces. From west to east, the first of these is the Appalachian Plateau, the smallest of the provinces, located in the southwestern tip of the state. The next two provinces run from northeast to southwest, generally paralleling the state's western boundary. The Valley and Ridge province consists of linear ridges in its western segment and the Great Appalachian Valley (also known as the Great Valley) in its eastern region. The Blue Ridge province is mostly a region of rugged mountains, part of a range stretching southwestward from Pennsylvania to South Carolina. The state's highest point, Mount Rogers (Rogers, Mount), at an elevation of 5,729 feet (1,746 metres), lies in the Blue Ridge area.In central Virginia the Piedmont province (part of the larger Piedmont region of the eastern United States) consists of lower rolling hills, reaching from the Blue Ridge to the fall line, the place where rivers descend, often in rapids, from higher and geologically older regions onto the flatter coastal plains. To the east the Coastal Plain province—or Tidewater region—lies low between the fall line and the Atlantic coast. The province is deeply interlaced by tidal rivers and is dominated by the Northern Neck Peninsula, the Middle Peninsula, and the Virginia Peninsula—all west of Chesapeake Bay. East of the Chesapeake and separated from the rest of the state is the Eastern Shore, the southern tip of the Delmarva Peninsula, which Virginia shares with Delaware and with Maryland's Eastern Shore. The Tidewater also contains the area south of the James River, including the Norfolk region and the Great Dismal Swamp, which spans 750 square miles (1,940 square km) and extends south into North Carolina.

Drainage and soils

Virginia has eight major drainage systems that empty into the Atlantic Ocean. The Potomac River receives the waters of the north-flowing Shenandoah River at Harpers Ferry, in West Virginia, and becomes the state's border with Maryland on its way to Chesapeake Bay. The Rappahannock (Rappahannock River), York, and James (James River) rivers indent the coast to form the main peninsulas. Two other systems pass into North Carolina, while in the extreme southwestern corner of the state two major systems flow eventually into the Gulf of Mexico (Mexico, Gulf of).

The soils of Virginia are generally fertile. In the Tidewater, the tidal lowlands are usually covered with loam, a mixed soil rich in organic materials. To the west, sandy loams and clays predominate. In the Piedmont, clay and limestone soils dominate, and limestone soils are found in the valley areas west of the Blue Ridge.

Climate

The state's climate, generally mild and equable, varies according to elevation and proximity to Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. In southeastern Virginia and the Eastern Shore, January temperatures average about 40 °F (4 °C); July temperatures average in the upper 70s F (about 26 °C). These temperatures allow growing seasons of up to eight months, three months longer than those in far western Virginia. Elsewhere in the Tidewater and Piedmont regions, continental weather overcomes the eastern marine influence to produce colder winters. In the mountains winter temperatures of 0 °F (−18 °C) may occur, and cool nights in summer follow daytime highs that usually stay below 90 °F (32 °C). Throughout the state, precipitation averages from about 32 to 44 inches (810 to 1,120 mm). Snowfall averages from a few inches in the southeast to about 30 inches (760 mm) in the mountains.

Plant and animal life

Forests of the Tidewater and Piedmont areas have mainly pine and some hardwood. Cover other than trees includes marsh grass in the Tidewater and broom sedge, crabgrass, wire grass, and cultivated crops elsewhere. The mountainous areas contain tracts of various coniferous species and hardwoods such as hickory and oak. Bluegrass and field crops generally cover nearby valleys. Wildflowers and berry bushes abound, depending on climate and soils.

Forests of the Tidewater and Piedmont areas have mainly pine and some hardwood. Cover other than trees includes marsh grass in the Tidewater and broom sedge, crabgrass, wire grass, and cultivated crops elsewhere. The mountainous areas contain tracts of various coniferous species and hardwoods such as hickory and oak. Bluegrass and field crops generally cover nearby valleys. Wildflowers and berry bushes abound, depending on climate and soils. At the time of European settlement of the Great Valley of Virginia in the early 18th century, large herds of native bison were prevalent along the banks of the Shenandoah River, but, as elsewhere, the bison populations were destroyed as settlers moved westward. Black bears still are found in Virginia's mountains and in the Great Dismal Swamp. Common fauna are rabbits, chipmunks, squirrels, opossums, muskrats, woodchucks, foxes, and deer. Less common are otters, beavers, mink, and wildcats. The main game birds are doves, quail, ducks, and geese; a few wild turkeys and woodcocks may be found. Scavengers include coastal seagulls and the ubiquitous turkey vulture. Predatory birds include a number of hawks, owls, and the golden and bald eagles. There are numerous songbirds, including the cardinal, the state bird. Poisonous reptiles include rattlesnakes, copperheads, and water moccasins. Game fish and smaller panfish abound in Virginia's inland waters and offshore. Chesapeake Bay is one of the world's richest marine-life estuaries, noted for finfish, blue crabs, oysters, and clams. Although some yearly commercial and sport fishing catches have suggested generally plentiful stocks, concerns have been raised about overfishing and the diminishing populations of some species.

At the time of European settlement of the Great Valley of Virginia in the early 18th century, large herds of native bison were prevalent along the banks of the Shenandoah River, but, as elsewhere, the bison populations were destroyed as settlers moved westward. Black bears still are found in Virginia's mountains and in the Great Dismal Swamp. Common fauna are rabbits, chipmunks, squirrels, opossums, muskrats, woodchucks, foxes, and deer. Less common are otters, beavers, mink, and wildcats. The main game birds are doves, quail, ducks, and geese; a few wild turkeys and woodcocks may be found. Scavengers include coastal seagulls and the ubiquitous turkey vulture. Predatory birds include a number of hawks, owls, and the golden and bald eagles. There are numerous songbirds, including the cardinal, the state bird. Poisonous reptiles include rattlesnakes, copperheads, and water moccasins. Game fish and smaller panfish abound in Virginia's inland waters and offshore. Chesapeake Bay is one of the world's richest marine-life estuaries, noted for finfish, blue crabs, oysters, and clams. Although some yearly commercial and sport fishing catches have suggested generally plentiful stocks, concerns have been raised about overfishing and the diminishing populations of some species.People

Population (Virginia) composition

Nearly three-fourths of Virginia's residents are of white European descent. However, African Americans constitute a substantial minority—about one-fifth of the population—serving as a reminder of the important role that African slaves and their descendants played in the early development of the state. Native Americans (Native American) account for a tiny fraction of Virginia's population. The state's Hispanic community has been growing rapidly since the late 20th century. A small but nonetheless significant proportion of Virginia's residents are foreign-born; immigrant peoples of various ethnicities and their families are concentrated primarily in the northern counties surrounding Washington, D.C. (Washington)

The first Europeans to settle most of eastern Virginia were the English, coming from the central and southern counties of England, especially from London and the surrounding areas. During the 1700s the Welsh and the French Huguenots (Huguenot) were prominent among the immigrants, and a large number of people of Scotch-Irish and German descent moved from Pennsylvania into the Shenandoah Valley. People of Scotch-Irish and English ancestry still predominate, notably in western and southwestern counties. Over the centuries, differences in speech developed as a result of both class structure and isolation. Rural speech was largely localized, the more mainstream patterns attaining a wider regional usage. Virginia's principal speech patterns are Southern, but population mobility has diffused the local patterns and introduced others from different parts of the United States.

When the English colonists founded Jamestown (Jamestown Colony), England's first permanent settlement in North America, in 1607, native (Native American) peoples lived all around them. In the territory that now constitutes the state of Virginia, these peoples belonged primarily to three language families: the Algonquian (Algonquian languages), the Iroquoian, and the Siouan (Siouan languages). Estimates of the Algonquian-speaking population at the time of European settlement range roughly from 14,000 to 22,000 in the Tidewater region alone. Today only two reservations remain in the state, one each for the Pamunkey and Mattaponi peoples, respectively situated along the Pamunkey and Mattaponi rivers near West Point, where the two waterways join to form the York River at the western edge of the Middle Peninsula. Although some Native Americans live throughout the state—especially in the urban environs of Washington, D.C., the Norfolk– Virginia Beach– Newport News region, and Roanoke—the only other concentration in Virginia is that of the Chickahominy, clustering near the Chickahominy River, a tributary of the James River, in the central Tidewater region. The Pamunkey, Mattaponi, and Chickahominy all are Algonquian-speaking peoples.

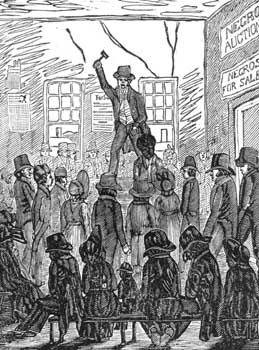

Africans were first taken to Jamestown in 1619 as indentured servants; legalized slavery was not introduced for several decades. However, slaves of African descent ultimately became the foundation of the plantation agriculture that began in the Tidewater area and spread into the Piedmont. At the start of the American Civil War, about half the state's population was black. Although this proportion has decreased significantly since that time, the absolute number of African Americans has increased dramatically.

The Anglican (Anglicanism) branch of Christianity was the official religion in colonial Virginia. Bruton Parish Church in Williamsburg, still active, was the main church in the early colonial capital; the church structure was completed in 1683. The Anglican church, which was disestablished in the colonies during the American Revolution, became the Episcopal Church, USA (Episcopal Church in the United States of America), but it retained only one-third of the Virginian population that claimed adherence to a specific denomination. Dissenters, primarily Presbyterians (presbyterian), Quakers (Quaker), Baptists (Baptist), and Methodists (Methodism), made up the Protestant balance. Virginia continues its Protestant (Protestant Heritage) tradition today, although there are many Roman Catholics (Roman Catholicism). The largest Protestant denominations are the Southern Baptist (Southern Baptist Convention), United Methodist (United Methodist Church), Episcopalian, and Presbyterian churches.

Settlement patterns

For more than a century, the greatest growth has occurred in the urban corridor, an area that stretches south from Washington, D.C., through Arlington county and the city of Alexandria to Richmond before bending southeast to the Hampton Roads area, which comprises the towns of Newport News, Hampton, Norfolk, Virginia Beach, and Portsmouth. This corridor is often classified as an extension of the great population mass, or megalopolis, arcing across the northeastern United States from Boston to Washington, D.C. Other metropolitan areas include the urban environs of Roanoke and Lynchburg, as well as those around the smaller cities of Danville, Bristol, and Charlottesville.

For more than a century, the greatest growth has occurred in the urban corridor, an area that stretches south from Washington, D.C., through Arlington county and the city of Alexandria to Richmond before bending southeast to the Hampton Roads area, which comprises the towns of Newport News, Hampton, Norfolk, Virginia Beach, and Portsmouth. This corridor is often classified as an extension of the great population mass, or megalopolis, arcing across the northeastern United States from Boston to Washington, D.C. Other metropolitan areas include the urban environs of Roanoke and Lynchburg, as well as those around the smaller cities of Danville, Bristol, and Charlottesville.The increase in agricultural mechanization and productivity, with an attendant decrease in acreage and number of farms, has sent both black and white Virginians to the cities for their livelihood. The population of Richmond is more than one-half African American; rural Charles City county, lying in the urban corridor, also is largely black. However, the counties to the west of the Blue Ridge have mainly small family-run farms, and the African American population is small in comparison with those of the Piedmont and Tidewater regions.

Economy

Virginia has developed a well-balanced economy far beyond its original agricultural base, and since the 1960s the state's annual economic productivity usually has been slightly higher than that of the United States as a whole. Farming now accounts for just a tiny fraction of the total yearly value of the state's goods and services, and manufacturing, while a leading sector in the mid-20th century, has been surpassed by the services sector. The high-technology sector has expanded considerably since the late 20th century, especially in the suburbs of Washington, D.C., although Hampton Roads and the city of Richmond also have become areas of concentration. The federal government has remained a dominant economic presence in Virginia. Indeed, the many military institutions within the state's boundaries (as well as headquarters of the Central Intelligence Agency) and Virginia's proximity to Washington, D.C., have supported economic growth. Virginia ranks among the top states in per capita distribution of federal funds and has one of the highest per capita incomes in the Southern region.

Agriculture, forestry, and fishing

Once the heart of Virginia's economy, agriculture, forestry, and fishing now constitute less than 1 percent of the state's gross product, and the sector employs just a small segment of the workforce. At the time of colonization in the 17th century, European settlers learned tobacco cultivation from the local indigenous populations, and tobacco became the mainstay of Virginia's early agricultural economy. Although other products now predominate, tobacco is still featured in the southern Piedmont region. Truck farms devoted to market produce dot the Eastern Shore and Norfolk areas. Other sorts of farms are spread throughout the state.

Poultry, cattle and dairy products, grains and feeds, and vegetables are the state's principal agricultural products. Rockingham county in the Shenandoah Valley is home to one of the country's major turkey-raising operations. Although not among the primary products, Virginia's apples and peaches are famous, especially those from the orchards around Winchester and in other areas of the northwestern region.

Virginia's forestry industry taps both the hardwood resources from the uplands and pine from the lower-lying areas. Hardwood boards are the primary product of the state's sawmills. Pine is the principal pulpwood. Since the 1970s the government has implemented reforestation programs to counter the risk of overharvesting—particularly of pine resources.

Virginia's fisheries (commercial fishing) operate both in Chesapeake Bay and in the Atlantic Ocean. Products from the bay include flounder, bass, and a number of other edible finfish, as well as oysters, hard and soft clams, and blue crabs. Large amounts of schooling menhaden are caught in large nets and processed for their oil and for protein-rich fish meal. Considerable quantities of sea clams and scallops are harvested in the Atlantic, and large ocean fish, such as swordfish and tuna, are caught on baited hooks strung out on lines that are suspended relatively close to the ocean's surface. Aquaculture, focusing primarily on hard clams and oysters, has grown notably since the turn of the 21st century. Virginia and Maryland both have passed antipollution laws aimed to conserve Chesapeake Bay as a safe environment for fishing as well as general recreation.

Resources and power

The main commercial minerals mined in Virginia include coal (coal mining) from the southwest and stone, clay, sand, and gravel from many areas. Nearly half the state's power is drawn from coal, while nuclear (nuclear energy) generators provide about one-third of Virginia's energy. Petroleum and natural gas each account for just a small portion of the state's power production.

Manufacturing

Manufacturing generates less than one-tenth of Virginia's gross product and employs a comparable proportion of the workforce. Tobacco and chemical products are among the state's main manufactures. Other nondurable goods include food, textiles, and apparel. Transportation equipment is a leader among durable goods, but furniture, electrical equipment, and wood products also are important.

Services and labour

The services sector is by far the largest segment of Virginia's economy, accounting for more than two-thirds of the state's gross product. Of the various civilian service occupational sectors, wholesale and retail trade, health and social services, and the public sector (federal, state, and local government) account for a major portion of employment. Professional, scientific, and technical services are a significant source of employment in Virginia as well, with many jobs in the communications and business sectors.

The U.S. Department of Defense not only is a major employer in Virginia but also conducts a significant amount of business through contracts with private firms within the state. Military facilities in Virginia, including the Defense Department's headquarters at the Pentagon building in Arlington county (Arlington), cover more than 400 square miles (1,000 square km). The numerous military installations throughout the state offer training, engineering, supply, and transportation services, and all have had a considerable effect on local economic conditions and employment. Among the most prominent military establishments are the transportation-training centre for the army at Fort Eustis and, at historic Fort Monroe, the headquarters of the Army Training and Doctrine Command and the Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC) Cadet Command. Naval activities are concentrated around the Norfolk naval base, the largest U.S. Navy (United States Navy, The) installation in the world. The U.S. Marine Corps (United States Marine Corps, The) facility at Quantico is a major development and education base. The U.S. Air Force (United States Air Force, The) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) have major installations in the Hampton– Newport News area. The U.S. Coast Guard (United States Coast Guard) has a large facility near Yorktown, as do the U.S. Naval Weapons Station and the Naval Supply Center. Military intelligence training is conducted at Camp Peary Naval Reservation near Williamsburg, while the CIA, a civilian agency, is located in Langley.

The U.S. Department of Defense not only is a major employer in Virginia but also conducts a significant amount of business through contracts with private firms within the state. Military facilities in Virginia, including the Defense Department's headquarters at the Pentagon building in Arlington county (Arlington), cover more than 400 square miles (1,000 square km). The numerous military installations throughout the state offer training, engineering, supply, and transportation services, and all have had a considerable effect on local economic conditions and employment. Among the most prominent military establishments are the transportation-training centre for the army at Fort Eustis and, at historic Fort Monroe, the headquarters of the Army Training and Doctrine Command and the Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC) Cadet Command. Naval activities are concentrated around the Norfolk naval base, the largest U.S. Navy (United States Navy, The) installation in the world. The U.S. Marine Corps (United States Marine Corps, The) facility at Quantico is a major development and education base. The U.S. Air Force (United States Air Force, The) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) have major installations in the Hampton– Newport News area. The U.S. Coast Guard (United States Coast Guard) has a large facility near Yorktown, as do the U.S. Naval Weapons Station and the Naval Supply Center. Military intelligence training is conducted at Camp Peary Naval Reservation near Williamsburg, while the CIA, a civilian agency, is located in Langley.Transportation

Although the state's port facilities are among the busiest in the country, with the port of Hampton Roads a leading U.S. port in foreign tonnage, Virginia's major transportation facilities are roads, railroads, and airports. Most road traffic is north-south, adding to Virginia's status as a “bridge” state between the country's northeastern and southeastern regions. The striking 17.6-mile (28.3-km) Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel complex links Cape Charles on the Eastern Shore with Virginia Beach, east of Norfolk. Comprising a trestled roadway raised above the mouth of the bay and two tunnels (under the main shipping channels), it is one of the largest structures of its kind.

Although the state's port facilities are among the busiest in the country, with the port of Hampton Roads a leading U.S. port in foreign tonnage, Virginia's major transportation facilities are roads, railroads, and airports. Most road traffic is north-south, adding to Virginia's status as a “bridge” state between the country's northeastern and southeastern regions. The striking 17.6-mile (28.3-km) Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel complex links Cape Charles on the Eastern Shore with Virginia Beach, east of Norfolk. Comprising a trestled roadway raised above the mouth of the bay and two tunnels (under the main shipping channels), it is one of the largest structures of its kind.Virginia has a well-established rail system. A number of large railroad-based interstate transportation companies have their headquarters in the state. Several other companies operate shorter-line routes pitched primarily to commuters in the major metropolitan areas.

A network of commercial airports offers regional, national, and international flights. The largest and busiest of Virginia's airports are Washington Dulles International and Ronald Reagan Washington National, both major hubs in the Washington, D.C., area; Richmond International, Norfolk International, and Newport News–Williamsburg International airports have expanded notably since the late 20th century.

Government and society

Constitutional framework

The present revision of the Commonwealth of Virginia's constitution of 1776 was adopted in 1970 and ratified the following year. In it the state retains the organization of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. The only elected administrative officials are the governor, the lieutenant governor, and the attorney general; each serves a four-year term, and the governor is the only one who cannot serve consecutive terms. Virginia's General Assembly, a bicameral legislature, consists of a Senate of 33–40 members and a House of Delegates of 90–100 members. The Assembly meets annually in Richmond.

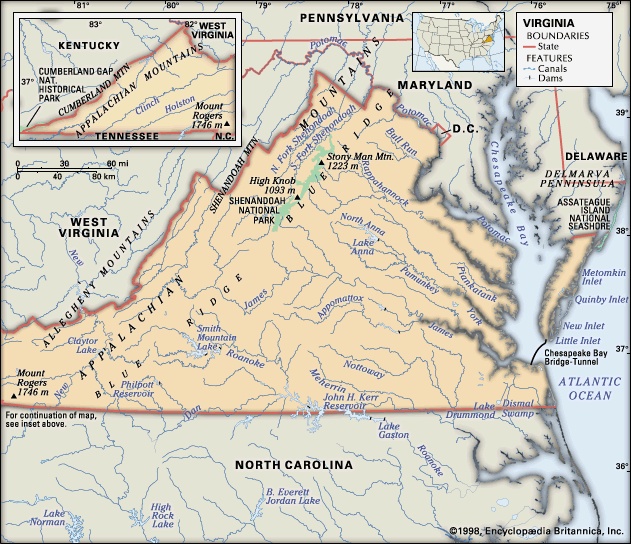

The present revision of the Commonwealth of Virginia's constitution of 1776 was adopted in 1970 and ratified the following year. In it the state retains the organization of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. The only elected administrative officials are the governor, the lieutenant governor, and the attorney general; each serves a four-year term, and the governor is the only one who cannot serve consecutive terms. Virginia's General Assembly, a bicameral legislature, consists of a Senate of 33–40 members and a House of Delegates of 90–100 members. The Assembly meets annually in Richmond.Local government includes 95 counties, hundreds of towns, and several dozen chartered cities. The counties and towns are governed by elected boards of supervisors. Cities are separate from county administration and are governed by elected councils employing city managers.

The Democratic Party thoroughly dominated state politics from its revival in 1883 until the Republican Party elected its first Virginia governor in a century, in 1969, and 6 of the state's 10 U.S. representatives, in 1970. In the following decades, the two parties competed closely for domination of the state's congressional delegation. Although the General Assembly long remained substantially Democratic, representation of the two parties in both the House of Delegates and the Senate had become more balanced by the early 21st century.

The Virginia judicial system comprises four levels of courts. The seven judges of the Supreme Court of Virginia, the highest state judicial body, are elected to staggered 12-year terms by the General Assembly. The primary work of this court includes hearing criminal and domestic appeals from the Court of Appeals (United States Court of Appeals) of Virginia and civil appeals from the circuit courts; exercising original jurisdiction over cases of habeas corpus, mandamus, and matters filed by the Judicial Inquiry and Review Commission; and developing the body of Virginia common law. The primary purpose of the Court of Appeals is to expand judicial capacity to relieve the immense backlog of criminal and domestic cases pending before the Supreme Court. There are 11 judges on this court, elected by the General Assembly to eight-year terms. The 31 judicial circuits are the courts of general jurisdiction in Virginia. Judges of these courts are elected to eight-year terms by the General Assembly. Other courts, with limited jurisdiction, include general district (municipal and county), juvenile, and domestic-relations courts. In addition, all judicial circuits have magistrates who have the authority to issue warrants but lack trial jurisdiction. Counties and cities have a commonwealth's attorney, whose main job is criminal prosecution.

Health and welfare

Public and private facilities in Virginia share in providing health care. Among the state's major public health services are drinking water and wastewater treatment, immunization, and care for the mentally ill and for children with disabilities. Welfare and public assistance are administered in conjunction with local welfare boards and superintendants.

Education

Virginia's public school system was established in 1846. In the 21st century the Virginia Board of Education supervises public primary and secondary education, and the State Council of Higher Education coordinates postsecondary public education. Virginia has a strong public community-college system, with branches throughout the state.

Virginia's four-year colleges and universities are numerous. They include both public institutions, funded by the state, and private ones, many of which were founded by religious denominations. Among the best known are the College of William and Mary (William and Mary, College of) in Williamsburg, a state institution founded in 1693 and the second oldest college in the country, and the University of Virginia (Virginia, University of) in Charlottesville, founded in 1819 largely as the creation of Thomas Jefferson (Jefferson, Thomas) both in its organization and in the design of its buildings and grounds. Virginia Tech, established in Blacksburg in 1872, is a large land-grant college. James Madison University, founded in Harrisonburg in 1908, was previously a state teachers college for women. Also widely recognized are the private Washington and Lee University (1749) and the state-supported Virginia Military Institute (1839), both located in Lexington. Virginia also has a number of historically black universities. The private Hampton University (1868) is nationally recognized, and Norfolk State University (1935) is Virginia's largest predominantly black public postsecondary institution.

Several urban state universities have developed into major institutions since the 1960s. Most of these were once auxiliary campuses of larger institutions. George Mason University (1957), in Fairfax, originally was a northern-Virginia branch of the University of Virginia. Virginia Commonwealth University (1838), in Richmond, has a historical affiliation with the College of William and Mary, as does Old Dominion University (1930), in Norfolk.

Cultural life

Virginians enjoy a lively cultural life, rooted largely in the state's colonial history and in its central role in the early development of the United States. Virginia has more than 100 historical societies and museums. Most notable is the Virginia Historical Society in Richmond, which houses one of the most extensive collections of materials pertaining to colonial America and to the early republic; the society regularly exhibits segments of its holdings.

Virginians enjoy a lively cultural life, rooted largely in the state's colonial history and in its central role in the early development of the United States. Virginia has more than 100 historical societies and museums. Most notable is the Virginia Historical Society in Richmond, which houses one of the most extensive collections of materials pertaining to colonial America and to the early republic; the society regularly exhibits segments of its holdings. Millions of visitors annually are attracted to the state's historical sites as well. Foremost among these is Colonial Williamsburg, a living museum staffed by highly trained historical interpreters, who, dressed in period clothing, reenact various aspects of colonial life in and around the town's expertly restored 17th- and 18th-century buildings. Striking examples of colonial architecture also are found at such preserved homes as George Washington's Mount Vernon, near Washington, D.C., and Thomas Jefferson's Monticello, near Charlottesville. Monticello and the nearby University of Virginia (Virginia, University of) are of particular interest to historians of art and architecture. Finally, monuments of the American Civil War abound in Virginia. In the northern part of the state, the battlefield known to Southerners as Manassas and to Northerners as Bull Run is particularly significant; notable in the south-central region is Appomattox Court House, the site of Gen. Robert E. Lee (Lee, Robert E.)'s surrender to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant (Grant, Ulysses S.) in 1865.

Millions of visitors annually are attracted to the state's historical sites as well. Foremost among these is Colonial Williamsburg, a living museum staffed by highly trained historical interpreters, who, dressed in period clothing, reenact various aspects of colonial life in and around the town's expertly restored 17th- and 18th-century buildings. Striking examples of colonial architecture also are found at such preserved homes as George Washington's Mount Vernon, near Washington, D.C., and Thomas Jefferson's Monticello, near Charlottesville. Monticello and the nearby University of Virginia (Virginia, University of) are of particular interest to historians of art and architecture. Finally, monuments of the American Civil War abound in Virginia. In the northern part of the state, the battlefield known to Southerners as Manassas and to Northerners as Bull Run is particularly significant; notable in the south-central region is Appomattox Court House, the site of Gen. Robert E. Lee (Lee, Robert E.)'s surrender to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant (Grant, Ulysses S.) in 1865.The fine arts are an active concern of the state government, as well as of private patrons. The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond was the first state museum of the arts when it was established in 1934. The Barter Theatre was founded by actor Robert Porterfield in 1933 in the tiny southwestern town of Abingdon; its original charge for admission was produce, handicrafts, or whatever the prospective viewer could afford. Dozens of art galleries are located throughout Virginia. There are several ballet companies, orchestras, civic choruses, and opera and theatre companies, as well as numerous festivals of the arts. bluegrass and mountain-music festivals are especially popular in the summer months.

The natural beauty of Virginia offers much in the way of recreation. Shenandoah National Park, in the Blue Ridge, has an abundance of wildlife and unusual geological formations, while Assateague Island National Seashore, off the eastern coast of the Delmarva Peninsula and divided between Virginia and Maryland, is especially noted for its wild horses. The broad sands of Virginia Beach, on the state's southeastern coast near the entrance to the Chesapeake Bay, attract many visitors annually. Among the many scenic routes are the Skyline Drive and Blue Ridge Parkway, which join at Rockfish Gap to form a continuous road following the crest of the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia and North Carolina; both offer spectacular views and park facilities. The Colonial Parkway, connecting Jamestown, Williamsburg, and Yorktown, is attractive from both natural and historical perspectives; planned in the 1930s, this road has only two lanes.

The state has no professional sports teams, but collegiate athletics, particularly the Virginia Tech and University of Virginia gridiron football and basketball teams, attract a broad following. The James River provides challenging rapids for enthusiasts of white-water canoeing, rafting, and other aquatic adventure sports, and the state's mountain resorts, including Homestead, Bryce, Massanutten, and Wintergreen, offer fine slopes for downhill skiing. Golfing is also a popular pastime.

Of the more than two dozen daily newspapers that serve Virginia's residents, The Washington Post is the most widely read. The Richmond Times-Dispatch and The Virginian-Pilot, based in Norfolk, cover their respective metropolitan areas. Arlington is the home of USA Today, which in the 1990s became one of the country's most influential news organs. Several scholarly and popular historical journals published in Virginia enjoy a national readership. The state also has dozens of television stations and more than 100 radio stations.

History (Virginia)

Early peoples

The original inhabitants of Virginia arrived some 10,000 to 12,000 years ago. These were people of Paleo-Indian culture, who, like their successors, the Archaic-culture (Archaic culture) people, lived mainly by hunting and fishing. From about 1000 BCE the Woodland culture (Woodland cultures) began to make pottery and to grow such crops as corn (maize), beans, and squash. The coastal areas of eastern Virginia supported a significant population of indigenous peoples who fished in the rivers and bays and hunted wild fowl. At the time of European settlement, in the early 17th century, various tribal groups lived in the area. However, the early English settlers dealt mostly with the Powhatan confederacy, an alliance of some 30 Algonquian (Algonquian languages)-speaking peoples of the Tidewater region, united under the powerful chief Powhatan.

The original inhabitants of Virginia arrived some 10,000 to 12,000 years ago. These were people of Paleo-Indian culture, who, like their successors, the Archaic-culture (Archaic culture) people, lived mainly by hunting and fishing. From about 1000 BCE the Woodland culture (Woodland cultures) began to make pottery and to grow such crops as corn (maize), beans, and squash. The coastal areas of eastern Virginia supported a significant population of indigenous peoples who fished in the rivers and bays and hunted wild fowl. At the time of European settlement, in the early 17th century, various tribal groups lived in the area. However, the early English settlers dealt mostly with the Powhatan confederacy, an alliance of some 30 Algonquian (Algonquian languages)-speaking peoples of the Tidewater region, united under the powerful chief Powhatan.The colonial period

The purposes of the representatives of the Virginia Company of London, who landed at present-day Jamestown (Jamestown Colony) in May 1607, were not only to colonize but also to Christianize, to open new areas for trade, and to guard against further inroads by the Spanish, who already had colonized what is now Florida. Hunger, poor shelter, hostility from the indigenous peoples, and rampant disease plagued the company's early years, but, while the settlement tottered constantly on the brink of dissolution, a tobacco industry was established by John Rolfe (Rolfe, John) and a representative assembly was convened. Rolfe's marriage in 1614 to Pocahontas, daughter of Powhatan, brought temporary peace between the indigenous populations and the English; however, after the death of Pocahontas and her father, a war broke out between the two groups. In 1624 the company's charter was revoked, and Virginia was established as England's first royal colony. In the following years new settlements were made, and local administrative systems were developed.

The purposes of the representatives of the Virginia Company of London, who landed at present-day Jamestown (Jamestown Colony) in May 1607, were not only to colonize but also to Christianize, to open new areas for trade, and to guard against further inroads by the Spanish, who already had colonized what is now Florida. Hunger, poor shelter, hostility from the indigenous peoples, and rampant disease plagued the company's early years, but, while the settlement tottered constantly on the brink of dissolution, a tobacco industry was established by John Rolfe (Rolfe, John) and a representative assembly was convened. Rolfe's marriage in 1614 to Pocahontas, daughter of Powhatan, brought temporary peace between the indigenous populations and the English; however, after the death of Pocahontas and her father, a war broke out between the two groups. In 1624 the company's charter was revoked, and Virginia was established as England's first royal colony. In the following years new settlements were made, and local administrative systems were developed. The governorship of Sir William Berkeley (Berkeley, Sir William)—begun in 1642, interrupted from 1652 to 1660 by Puritan (Puritanism) rule in England, and ended in 1677—marked the solidification of the colony. The many anti-Puritan supporters of Charles I who fled to Virginia after the king's death in 1649 added an important element to the population, much of which consisted of indentured servants of European or African descent. The first Africans had been taken to Virginia in 1619, but race-based slavery began to grow rapidly only after the 1660s. Soon the institution was protected by Virginia law, and the number of slaves in the colony rose steadily until the American Revolution (1775–83). (For a more detailed account of the nature of slavery in the colonies, see race: The history of the idea of race (race).)

The governorship of Sir William Berkeley (Berkeley, Sir William)—begun in 1642, interrupted from 1652 to 1660 by Puritan (Puritanism) rule in England, and ended in 1677—marked the solidification of the colony. The many anti-Puritan supporters of Charles I who fled to Virginia after the king's death in 1649 added an important element to the population, much of which consisted of indentured servants of European or African descent. The first Africans had been taken to Virginia in 1619, but race-based slavery began to grow rapidly only after the 1660s. Soon the institution was protected by Virginia law, and the number of slaves in the colony rose steadily until the American Revolution (1775–83). (For a more detailed account of the nature of slavery in the colonies, see race: The history of the idea of race (race).)In 1676 a rebellion of colonists led by Nathaniel Bacon (Bacon, Nathaniel), though short-lived, led to Berkeley's recall and signaled a growing desire for more self-government among the colonists. This sentiment intensified during the century that followed, when England attempted to govern fairly but did not allow the inhabitants of its American colonies the full rights of the English at home.

In 1699 the colony's capital was moved from Jamestown to Williamsburg. The next several decades were a period of expansion as well as of internal strengthening. Virginia had the largest population of any American colony, and, as tobacco crops wore out the soil, Virginians began to move steadily westward in search of new land. Settlers from the Tidewater region spilled over into the Piedmont, across the Blue Ridge, and, by the 1740s, into the Ohio country beyond, there running afoul of French ambitions for that region. For decades the popularly elected assembly of colonial Virginia, the House of Burgesses (Burgesses, House of), led the way in opposing royal prerogatives in the colony, and, following England's prohibition of westward expansion in 1763, a concerted drive to rationalize rebellion began. On the eve of the American Revolution, Virginia had more than 120,000 residents, many of them persons of considerable sophistication and learning, and a stable—if narrowly based—economy.

In 1699 the colony's capital was moved from Jamestown to Williamsburg. The next several decades were a period of expansion as well as of internal strengthening. Virginia had the largest population of any American colony, and, as tobacco crops wore out the soil, Virginians began to move steadily westward in search of new land. Settlers from the Tidewater region spilled over into the Piedmont, across the Blue Ridge, and, by the 1740s, into the Ohio country beyond, there running afoul of French ambitions for that region. For decades the popularly elected assembly of colonial Virginia, the House of Burgesses (Burgesses, House of), led the way in opposing royal prerogatives in the colony, and, following England's prohibition of westward expansion in 1763, a concerted drive to rationalize rebellion began. On the eve of the American Revolution, Virginia had more than 120,000 residents, many of them persons of considerable sophistication and learning, and a stable—if narrowly based—economy.Independence and statehood

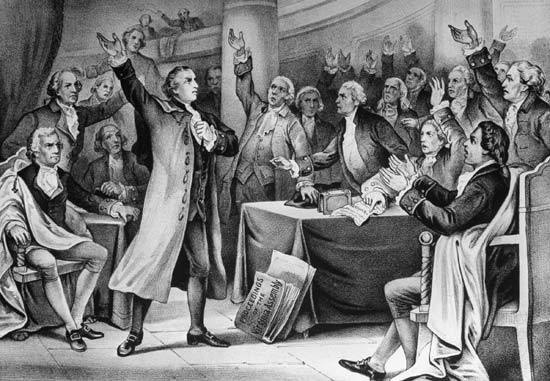

Virginians were among the leaders of the American Revolution and of the events leading to it, including the convening of the First Continental Congress, a body of delegates to speak on behalf of the colonies, in 1774. It was at a convention in Virginia in 1775 that the legislator Patrick Henry (Henry, Patrick) uttered his famous words, “Give me liberty or give me death!” Thomas Jefferson (Jefferson, Thomas) was the primary author of the Declaration of Independence, while George Washington (Washington, George) assumed command of the armies. It was at Yorktown that the British armies were forced to surrender to combined American and French forces on Oct. 19, 1781, which led to acknowledgement of the colonies' independence in the Treaty of Paris (part of the Peace of Paris (Paris, Peace of) collection of treaties) in 1783. In 1788 Virginia became the 10th state to ratify the Constitution (Constitution of the United States of America).

Virginians were among the leaders of the American Revolution and of the events leading to it, including the convening of the First Continental Congress, a body of delegates to speak on behalf of the colonies, in 1774. It was at a convention in Virginia in 1775 that the legislator Patrick Henry (Henry, Patrick) uttered his famous words, “Give me liberty or give me death!” Thomas Jefferson (Jefferson, Thomas) was the primary author of the Declaration of Independence, while George Washington (Washington, George) assumed command of the armies. It was at Yorktown that the British armies were forced to surrender to combined American and French forces on Oct. 19, 1781, which led to acknowledgement of the colonies' independence in the Treaty of Paris (part of the Peace of Paris (Paris, Peace of) collection of treaties) in 1783. In 1788 Virginia became the 10th state to ratify the Constitution (Constitution of the United States of America). The state continued its national leadership in the following decades, furnishing four of the first five presidents of the United States, including Jefferson (1801–09) and James Madison (Madison, James) (1809–17). Another Virginian, John Marshall (Marshall, John), served as chief justice of the United States from 1801 to 1835 and was largely responsible for establishing an independent federal judiciary in the early republic.

The state continued its national leadership in the following decades, furnishing four of the first five presidents of the United States, including Jefferson (1801–09) and James Madison (Madison, James) (1809–17). Another Virginian, John Marshall (Marshall, John), served as chief justice of the United States from 1801 to 1835 and was largely responsible for establishing an independent federal judiciary in the early republic.The state had abolished the African slave trade in 1778, and many of the revolutionary generation, including Washington, freed their slaves. (Jefferson was highly critical of the institution of slavery in his writing but freed only some of his slaves.) Nevertheless, the institution of slavery thrived in Virginia in the early 1800s, especially as slave owners began to sell their slaves to new plantation areas in the southeast. In 1831 Nat Turner (Turner, Nat), a slave preacher, encouraged a slave insurrection in Southampton county that resulted in many deaths and spread fear across the slaveholding South (South, the).

Civil War and Reconstruction

Controversy over the movement to abolish slavery intensified in the mid-19th century, particularly after the election of Abraham Lincoln (Lincoln, Abraham), an advocate of emancipation, to the presidency. The Southern states perceived an increasing threat to their agricultural livelihood, which was based on the institution of slavery; in 1861 Virginia followed 10 other Southern states in seceding from the Union to become the Confederate States of America, or the Confederacy. Richmond became the capital of the Confederacy, and Virginia was the chief battleground during the ensuing war—the American Civil War—between the United States of the North (North, the) and the Confederate States of the South (South, the).

Controversy over the movement to abolish slavery intensified in the mid-19th century, particularly after the election of Abraham Lincoln (Lincoln, Abraham), an advocate of emancipation, to the presidency. The Southern states perceived an increasing threat to their agricultural livelihood, which was based on the institution of slavery; in 1861 Virginia followed 10 other Southern states in seceding from the Union to become the Confederate States of America, or the Confederacy. Richmond became the capital of the Confederacy, and Virginia was the chief battleground during the ensuing war—the American Civil War—between the United States of the North (North, the) and the Confederate States of the South (South, the).

The Confederacy's Army of Virginia and the United States's Army of the Potomac engaged each other throughout the war. The most noteworthy encounters in Virginia included the battles of Bull Run (Bull Run, battles of) near Manassas in 1861 and 1862; the Seven Days' Battles near Richmond and the Battle of Fredericksburg (Fredericksburg, Battle of) in 1862; the Battle of Chancellorsville (Chancellorsville, Battle of) in 1863; and the Battle of the Wilderness (Wilderness, Battle of the) and the Petersburg Campaign in 1864–65. In April 1865 the Confederate commander Robert E. Lee (Lee, Robert E.) surrendered to the Union commander Ulysses S. Grant (Grant, Ulysses S.) at Appomattox Court House in southern Virginia to end the war. During the war the state lost one-third of its territory, the 50 counties west of the Allegheny Mountains, to the formation of a new antislavery state, West Virginia (1863).

The Confederacy's Army of Virginia and the United States's Army of the Potomac engaged each other throughout the war. The most noteworthy encounters in Virginia included the battles of Bull Run (Bull Run, battles of) near Manassas in 1861 and 1862; the Seven Days' Battles near Richmond and the Battle of Fredericksburg (Fredericksburg, Battle of) in 1862; the Battle of Chancellorsville (Chancellorsville, Battle of) in 1863; and the Battle of the Wilderness (Wilderness, Battle of the) and the Petersburg Campaign in 1864–65. In April 1865 the Confederate commander Robert E. Lee (Lee, Robert E.) surrendered to the Union commander Ulysses S. Grant (Grant, Ulysses S.) at Appomattox Court House in southern Virginia to end the war. During the war the state lost one-third of its territory, the 50 counties west of the Allegheny Mountains, to the formation of a new antislavery state, West Virginia (1863).

In 1867 Congress placed the South under military rule, and the Republican Party became the dominant political influence for a brief period. Under Republican Reconstruction in Virginia, African American men were granted the right to vote, education was improved, and a commitment was made to supporting and rebuilding the railroads. Virginia was readmitted as a state of the Union in 1870.

In 1867 Congress placed the South under military rule, and the Republican Party became the dominant political influence for a brief period. Under Republican Reconstruction in Virginia, African American men were granted the right to vote, education was improved, and a commitment was made to supporting and rebuilding the railroads. Virginia was readmitted as a state of the Union in 1870.Strife over the state debt, much of which had been accrued through the construction of railroads during the prewar period, was a prominent feature of Virginia's political life during the 1870s and '80s. When former Confederates in the Democratic Party regained control of the government, they provided for payment of the entire debt. The bankrupt state could not, however, meet its obligations to its citizens and pay interest to its creditors, and the new system of public schools, organized in 1870, suffered. Then in 1882 a group known as the Readjusters, claiming that the debt and interest needed pruning, seized control of the government (with the aid of the Republicans) and “readjusted” the debt downward.

Virginia's economy recovered slowly from the devastation of war. Agriculture remained the largest sector of the economy and tobacco the main crop, though it offered little latitude for development. The rebuilding and expansion of the railroad network created some new opportunities, as did the emergence in southwestern Virginia of timber and coal industries. The state's growing manufacturing sector, centred on textiles and cigarettes, also opened new avenues for growth.

Virginia, c. 1900–50

In 1902 the state adopted a new revision of its constitution that contained measures, such as a poll tax and a literacy test, that disenfranchised virtually all African Americans and most poor white citizens. For the first half of the 20th century, only a tiny fraction of Virginians were able to go to the polls. The Democratic Party dominated state politics for most of the period. Thomas Martin, U.S. senator from Virginia from 1893 to 1919, organized a Democratic program that emphasized low taxes, few government services, administrative efficiency, and white privilege. Harry F. Byrd, a newspaper editor and farmer who was elected governor in 1926 and U.S. senator in 1933, continued Martin's policies and consolidated control of the state. The Byrd organization dominated Virginia's politics into the 1960s.

After World War I the state's prosperity increased as agriculture diversified, manufacturing grew in importance, and tourism became a major enterprise. The Great Depression of the 1930s, although less severe in Virginia than in many other states, nevertheless devastated the agricultural and industrial sectors. However, World War I had established an important foundation of Virginia's future economy: federal government spending for military purposes. In the period before U.S. entry into World War II, Virginia was the first to set up a state defense system; the war then drew tens of thousands of soldiers into its military camps. The Hampton Roads area had a great boom with the expansion of the Norfolk naval base and the shipbuilding activities in Newport News. Employment continued at a high rate after the war, with ongoing growth in the nonagricultural sectors, including government.

Virginia since the mid-20th century

Following the U.S. Supreme Court's order in 1954 to desegregate public educational facilities, the Byrd administration, popularly called the “Byrd machine,” promoted a policy of “massive resistance” to the desegregation order. The schools of Prince Edward county gained nationwide attention by closing their doors from 1959 to 1964 rather than allowing black and white students to attend classes together. Although some large-scale protests against segregation took place in the state in the 1960s, Virginia experienced little of the violence that marked similar protests elsewhere in the South (South, the).

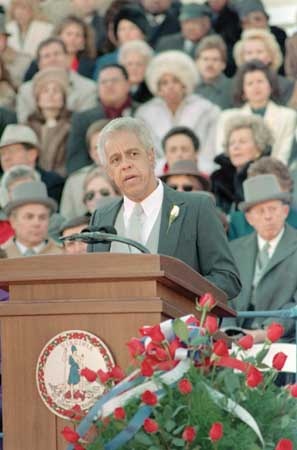

Byrd remained in office until 1965, and, after his death the following year, his organization collapsed. By the late 1960s segregation had ended, schools were open to both black and white students, and African Americans were voting freely. In 1989 Virginia elected its first African American governor, Douglas Wilder (Wilder, Douglas). Meanwhile, Virginia also developed solid two-party competition, with the Democratic and Republican parties controlling the state legislature and the governorship at various times. The Republicans generally have won most of Virginia's congressional seats and at least one of the state's two seats in the U.S. Senate since the 1960s.

Byrd remained in office until 1965, and, after his death the following year, his organization collapsed. By the late 1960s segregation had ended, schools were open to both black and white students, and African Americans were voting freely. In 1989 Virginia elected its first African American governor, Douglas Wilder (Wilder, Douglas). Meanwhile, Virginia also developed solid two-party competition, with the Democratic and Republican parties controlling the state legislature and the governorship at various times. The Republicans generally have won most of Virginia's congressional seats and at least one of the state's two seats in the U.S. Senate since the 1960s.During the last quarter of the 20th century and the early 21st century, Virginia experienced rapid suburban growth, especially in the vicinity of Washington, D.C., but also around Richmond and in the Hampton Roads area. Dynamic growth has taken place in the state's economy, notably in the government and technological segments of the service sector. Per capita income has remained above the national average, and the state has continued to devote a higher portion of its resources to education than have most other Southern states.

Additional Reading

Introductions to the state are provided by Writers' Program of the Work Projects Administration in the State of Virginia, Virginia: A Guide to the Old Dominion (1940, reissued 1992), still worth consulting; and Jean Gottman, Virginia in Our Century (1969), a comprehensive analysis through 1968. DeLorme Mapping Company, Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer, 5th ed. (2003), contains topographic maps. Local geography and history are combined in Raus McDill Hanson, Virginia Place Names (1969); and James Hagemann, The Heritage of Virginia: The Story of Place Names in the Old Dominion, 2nd ed. (1988). Edmund S. Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia (1975, reissued 2003), analyzes the social basis of early Virginian political thought; while J. Harvie Wilkinson III, Harry Byrd and the Changing Face of Virginia Politics, 1945–1966 (1968, reissued 1984), recounts more-recent events. Ben C. McCary, Indians in Seventeenth-Century Virginia (1957, reprinted 1992), briefly discusses the groups of Native Americans, their numbers, and their cultures at that time.Louis D. Rubin, Jr., Virginia: A History (1977, reissued 1984), provides a survey of the state's development over two centuries. Various periods in the state's past are described in Richard L. Morton, Colonial Virginia, 2 vol. (1960); Warren M. Billings, John E. Selby, and Thad W. Tate, Colonial Virginia: A History (1986); Virginius Dabney, Virginia, the New Dominion (1971, reprinted 1992); Parke Rouse, Virginia: The English Heritage in America (1966), on the period before the Civil War, with a short epilogue that gives a contemporary assessment of the state; and A.W. Moger, Virginia: Bourbonism to Byrd, 1870–1925 (1968). Raymond Gavins, The Perils and Prospects of Southern Black Leadership: Gordon Blaine Hancock, 1884–1970, 1st paperback ed. (1993; originally published 1977), provides valuable background on race relations in Virginia in the first half of the 20th century. Robert A. Pratt, The Color of Their Skin: Education and Race in Richmond, Virginia, 1954–1989 (1992), is an excellent study of school desegregation in Virginia. Scholarly articles on Virginia's history are printed in The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography (quarterly).