Georgia

Introduction

Georgian Sakartvelo, also called Republic of Georgia, Georgian Sakartvelos Respublika

Georgia, flag ofcountry of Transcaucasia located at the eastern end of the Black Sea on the southern flanks of the main crest of the Greater Caucasus Mountains. It is bounded on the north and northeast by Russia, on the east and southeast by Azerbaijan, on the south by Armenia and Turkey, and on the west by the Black Sea. Georgia includes three ethnic enclaves: Abkhazia, in the northwest (principal city Sokhumi); Ajaria, in the southwest (principal city Batʿumi); and South Ossetia, in the north (principal city Tsʿkhinvali). The capital of Georgia is Tʿbilisi (Tbilisi) (Tiflis).

The roots of the Georgian people extend deep in history; their cultural heritage is equally ancient and rich. During the medieval period a powerful Georgian kingdom existed, reaching its height between the 10th and 13th centuries. After a long period of Turkish and Persian domination, Georgia was annexed by the Russian Empire in the 19th century. An independent Georgian state existed from 1918 to 1921, when it was incorporated into the Soviet Union. In 1936 Georgia became a constituent (union) republic and continued as such until the collapse of the Soviet Union. During the Soviet period the Georgian economy was modernized and diversified. One of the most independence-minded republics, Georgia declared sovereignty on Nov. 19, 1989, and independence on April 9, 1991.

The 1990s were a period of instability and civil unrest in Georgia, as the first postindependence government was overthrown and separatist movements emerged in South Ossetia and Abkhazia.

The land

Relief, drainage, and soils

With the notable exception of the fertile plain of the Kolkhida Lowland—ancient Colchis, where the legendary Argonauts sought the Golden Fleece—the Georgian terrain is largely mountainous, and more than a third is covered by forest or brushwood. There is a remarkable variety of landscape, ranging from the subtropical Black Sea shores to the ice and snow of the crest line of the Caucasus. Such contrasts are made more noteworthy by the country's relatively small area.

The rugged Georgia terrain may be divided into three bands, all running from east to west.

To the north lies the wall of the Greater Caucasus range, consisting of a series of parallel and transverse mountain belts rising eastward and often separated by deep, wild gorges. Spectacular crest-line peaks include those of Mount Shkhara, which at 16,627 feet (5,068 metres) is the highest point in Georgia, and Mounts Rustaveli, Tetnuld, and Ushba, all of which are above 15,000 feet. The cone of the extinct Mkinvari (Kazbek) volcano dominates the northernmost Bokovoy range from a height of 16,512 feet. A number of important spurs extend in a southward direction from the central range, including those of the Lomis and Kartli (Kartalinian) ranges at right angles to the general Caucasian trend. From the ice-clad flanks of these desolately beautiful high regions flow many streams and rivers.

The southern slopes of the Greater Caucasus merge into a second band, consisting of central lowlands formed on a great structural depression. The Kolkhida Lowland, near the shores of the Black Sea, is covered by a thick layer of river-borne deposits accumulated over thousands of years. Rushing down from the Greater Caucasus, the major rivers of western Georgia, the Inguri, Rioni, and Kodori, flow over a broad area to the sea. The Kolkhida Lowland was formerly an almost continually stagnant swamp. In a great development program, drainage canals and embankments along the rivers were constructed and afforestation plans introduced; the region has become of prime importance through the cultivation of subtropical and other commercial crops.

To the east the structural trough is crossed by the Meskhet and Likh ranges, linking the Greater and Lesser Caucasus and marking the watershed between the basins of the Black and Caspian seas. In central Georgia, between the cities of Khashuri and Mtsʿkhetʿa (the ancient capital), lies the inner high plateau known as the Kartli (Kartalinian) Plain. Surrounded by mountains to the north, south, east, and west and covered for the most part by deposits of the loess type, this plateau extends along the Kura (Mtkvari) River and its tributaries.

The southern band of Georgian territory is marked by the ranges and plateaus of the Lesser Caucasus, which rise beyond a narrow, swampy coastal plain to reach 10,830 feet in the peak of Didi-Abuli.

A variety of soils are found in Georgia, ranging from gray-brown and saline semidesert types to richer red earths and podzols. Artificial improvements add to the diversity.

Climate

The Caucasian barrier protects Georgia from cold air intrusions from the north, while the country is open to the constant influence of warm, moist air from the Black Sea. Western Georgia has a humid subtropical, maritime climate, while eastern Georgia has a range of climate varying from moderately humid to a dry subtropical type.

There also are marked elevation zones. The Kolkhida Lowland, for example, has a subtropical character up to about 1,600 to 2,000 feet, with a zone of moist, moderately warm climate lying just above; still higher is a belt of cold, wet winters and cool summers. Above about 6,600 to 7,200 feet there is an alpine climatic zone, lacking any true summer; above 11,200 to 11,500 feet snow and ice are present year-round. In eastern Georgia, farther inland, temperatures are lower than in the western portions at the same altitude.

Western Georgia has heavy rainfall throughout the year, totaling 40 to 100 inches (1,000 to 2,500 millimetres) and reaching a maximum in autumn and winter. Southern Kolkhida receives the most rain, and humidity decreases to the north and east. Winter in this region is mild and warm; in regions below about 2,000 to 2,300 feet, the mean January temperature never falls below 32° F (0° C), and relatively warm, sunny winter weather persists in the coastal regions, where temperatures average about 41° F (5° C). Summer temperatures average about 71° F (22° C).

In eastern Georgia, precipitation decreases with distance from the sea, reaching 16 to 28 inches in the plains and foothills but increasing to double this amount in the mountains. The southeastern regions are the driest areas, and winter is the driest season; the rainfall maximum occurs at the end of spring. The highest lowland temperatures occur in July (about 77° F 【25° C】), while average January temperatures over most of the region range from 32° to 37° F (0° to 3° C).

Plant and animal life

Georgia's location and its diverse terrain have given rise to a remarkable variety of landscapes. The luxuriant vegetation of the moist, subtropical Black Sea shores is relatively close to the eternal snows of the mountain peaks. Deep gorges and swift rivers give way to dry steppes, and the green of alpine meadows alternates with the darker hues of forested valleys.

More than a third of the country is covered by forests and brush. In the west a relatively constant climate over a long time span has preserved many relict and rare items, including the Pitsunda pines (Pinus pithyusa). The forests include oak, chestnut, beech, and alder, as well as Caucasian fir, ash, linden, and apple and pear trees. The western underbrush is dominated by evergreens (including rhododendrons and holly) and such deciduous shrubs as Caucasian bilberry and nut trees. Liana strands entwine some of the western forests. Citrus groves are found throughout the republic, and long rows of eucalyptus trees line the country roads.

Eastern Georgia has fewer forests, and the steppes are dotted with thickets of prickly underbrush, as well as a blanket of feather and beard grass. Herbaceous subalpine and alpine vegetation occurs extensively in the highest regions. Animal life is very diverse. Goats and Caucasian antelope inhabit the high mountains; rodents live in the high meadows; and a rich birdlife includes the mountain turkey, the Caucasian black grouse, and the mountain and bearded eagles. The clear rivers and mountain lakes are full of trout.

Forest regions are characterized by wild boars, roe and Caucasian deer, brown bears, lynx, wolves, foxes, jackals, hares, and squirrels. Birds range from the thrush to the black vulture and hawk. Some of these animals and birds also frequent the lowland regions, which are the home of the introduced raccoon, mink, and nutria. The lowland rivers and the Black Sea itself are rich in fish.

Settlement patterns

Population densities are relatively high but are less than those for Armenia and Azerbaijan. The vast majority of the population lives below 2,600 feet; population density decreases with increasing altitude.

During the Soviet period the Georgian population increased, with a marked trend toward urbanization. More than half the population now lives in cities. Further, a considerable portion of the population that is defined as rural is, in fact, engaged in the urban economy of nearby cities. Enterprises for primary processing of agricultural products have been constructed in the villages, while ore-processing plants and light industry also are increasing in number. As a result, many of the slow-paced traditional villages have developed into distinctly modern communities. The number of rural inhabitants remains high because of the wide distribution of such labour-intensive branches of the economy as the tea and subtropical crop plantations.

Tʿbilisi, the capital, an ancient city with many architectural monuments mingling with modern buildings, lies in eastern Georgia, partly in a scenic gorge of the Kura River. Other major centres are Kʿutʿaisi, Rustʿavi, Sokhumi, and Batʿḱĩĭ

Tʿbilisi, the capital, an ancient city with many architectural monuments mingling with modern buildings, lies in eastern Georgia, partly in a scenic gorge of the Kura River. Other major centres are Kʿutʿaisi, Rustʿavi, Sokhumi, and BatʿḱĩĭThe people (Georgia)

The likelihood is great that the Georgians (whose name for themselves is Kartveli; “Georgian” derived from the Persian name for them, Gorj) have always lived in this region, known to them as Sakartvelo. Ethnically, contemporary Georgia is not homogeneous but reflects the intermixtures and successions of the Caucasus region. About seven-tenths of the people are Georgians; the rest consists of Armenians, Russians, Azerbaijanis, and smaller numbers of Ossetes, Greeks, Abkhazians, and other minor groups.

The likelihood is great that the Georgians (whose name for themselves is Kartveli; “Georgian” derived from the Persian name for them, Gorj) have always lived in this region, known to them as Sakartvelo. Ethnically, contemporary Georgia is not homogeneous but reflects the intermixtures and successions of the Caucasus region. About seven-tenths of the people are Georgians; the rest consists of Armenians, Russians, Azerbaijanis, and smaller numbers of Ossetes, Greeks, Abkhazians, and other minor groups.The Georgian language is a member of the Kartvelian (South Caucasian) family of languages. It has its own alphabet, which is thought to have evolved about the 5th century AD, and there are many dialects. A number of other Caucasian languages are spoken by minority groups; many are unwritten.

Many Georgians are members of the Georgian Orthodox church, an autocephalous Eastern Orthodox church. In addition, there are Muslim, Russian Orthodox, Armenian Apostolic, and Jewish communities.

The Georgians are a proud people with an ancient culture. They have through the ages been noted as warriors as well as for their hospitality, love of life, lively intelligence, sense of humour, and reputed longevity (although statistical data do not support this latter assertion).

The economy

The Georgian economy includes diversified and mechanized agriculture alongside a well-developed industrial base. Agriculture accounts for about half of the gross domestic product and employs about one-fourth of the labour force; the industry and service sectors each employ about one-fifth of the labour force.

After independence the Georgian economy contracted sharply, owing to political instability (which discouraged foreign investment), the loss of favourable trading relationships with the states of the former Soviet Union, and the civil unrest in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, where key pipelines and transport links were sabotaged or blockaded. Georgia sought to transform its command economy into one organized on market principles: prices were liberalized, the banking system reformed, and some state enterprises and retail establishments privatized.

Resources

The interior of Georgia has coal deposits (notably at Tqvarchʿeli and Tqibuli), petroleum (at Kazeti), and a variety of other resources ranging from peat to marble. The manganese deposits of Chiatʿura rival those of India, Brazil, and Ghana in quantity and quality. Its waterpower resources are also considerable. The deepest and most powerful rivers for hydroelectric purposes are the Rioni and its tributaries, the Inguri, Kodori, and Bzyb. Such western rivers account for three-fourths of the total capacity, with the eastern Kura, Aragvi, Alazani, and Khrami accounting for the rest. Oil deposits have been located near Batʿumi and Potʿi under the Black Sea.

Agriculture

A distinctive feature of the Georgian economy is that agricultural land is both in short supply and difficult to work; each patch of workable land, even on steep mountain slopes, is valued highly. The relative proportion of arable land is low. The importance of production of labour-intensive (and highly profitable) crops, such as tea and citrus fruits, is, however, a compensatory factor.

The introduction of a system of collective farms (kolkhozy (kolkhoz)) and state farms (sovkhozy (sovkhoz)) by the Soviet government in 1929–30 radically altered the traditional structure of landowning and working, though a considerable portion of Georgia's agricultural output continued to come from private garden plots. Contemporary agriculture uses modern equipment supplied under a capital investment program, which also finances the production of mineral fertilizers and herbicides, as well as afforestation measures. A program of land privatization was undertaken in 1992.

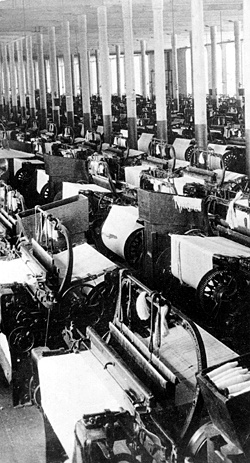

Tea plantations occupy more than 150,000 acres (60,000 hectares) and are equipped with modern picking machinery.

The vineyards of the republic constitute one of the oldest and most important branches of Georgian agriculture, and perhaps the best loved. Georgian winemaking dates to 300 BC; centuries of trial and error have produced more than 500 varieties of grape.

Orchards occupy some 320,000 acres throughout the country. Georgian fruits are varied; even slight differences in climate and soil affect the yield, quality, and taste of the fruit.

Sugar beets and tobacco are especially significant among other commercial crops. Essential oils (geranium, rose, and jasmine) also are produced to supply the perfume industry. Grains, including wheat, are important, but quantities are insufficient for the country's needs, and wheat must be imported. Growing of vegetables and melons has developed in the suburbs.

Livestock raising is marked by the use of different summer and winter pastures. Sheep and goats, cattle, and pigs are raised. Poultry, bees, and silkworms are also significant. Black Sea fisheries concentrate on flounder and whitefish.

Industry

The fuel and power foundation developed in Georgia has served as the base for industrialization. Dozens of hydroelectric stations, including the Rioni and Sokhumi plants, as well as many stations powered by coal and natural gas, have been constructed. All are now combined into a single power system, an organic part of the Transcaucasian system.

The coal industry is one of the oldest mineral extraction industries, centred on the restructured Tqibuli mines. Deposits found in Tqvarchʿeli and Akhaltsʿikhe have increased production.

Manganese and nonmetallic minerals ranging from talc to marble supply various industries throughout the countries of the former Soviet Union. The Rustʿavi (Rustavi) metallurgical plant, located near the capital, produced its first steel in 1956. There are markets for its laminated sheet iron and seamless pipe products in Russia, Ukraine, and elsewhere. Zestapʿoni is the second major metallurgical centre.

The machine-building industry produces a diverse range of products, from electric railway locomotives, heavy vehicles, and earth-moving equipment to lathes and precision instruments. Specialized products include tea-gathering machines and antihail devices for the country's plantations. Production is centred in the major cities.

The chemical industry of Georgia produces mineral fertilizers, synthetic materials and fibres, and pharmaceutical products. The building industry, using local raw materials, supplies the country with cement, slate, and many prefabricated reinforced-concrete structures and parts.

Commonly used manufactured goods were previously imported in large part from the republics of the former Soviet Union, but a ramified system of light industries set up in major consumption areas in Georgia now produces cotton, wool, and silk fabrics, as well as items of clothing.

Products of the food industry include tea and table and dessert wines. Brandy and champagne production is also well developed. Other food-industry activities include dairying and canning.

Transportation

Georgia has a dense transportation system. Most freight is carried by truck, but railways are important. Tʿbilisi is connected by rail with both Sokhumi and Batʿumi on the Black Sea and Baku on the Caspian.

An oil pipeline connects Batʿumi with Baku, Azerbaijan; two natural gas pipelines run from Baku to Tʿbilisi and then turn north to Russia. The seaports of Batʿumi, Potʿi, and Sokhumi are of major economic importance for the whole of Transcaucasia. The country's international airport is at Tʿbilisi.

Administration and social conditions

Government

In 1992 Georgia—which had been operating under a Soviet-era constitution from 1978—reinstated its 1921 pre-Soviet constitution. A constitutional commission was formed in 1992 to draft a new constitution, and after a protracted dispute over the extent of the authority to be accorded the executive a new document was adopted in 1995.

The head of state is the president, who is given extensive authority. A prime minister and cabinet are appointed by the president. The legislature is a 235-member Supreme Council. The judicial system includes district and city courts and a Supreme Court.

The Communist Party of Georgia, controlled by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, was until the 1980s the only political party. With the increase in nationalist sentiment and the reforms of the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, many diverse political groups emerged. Major political organizations now include the Citizens' Union, an alliance formed by the Georgian president Eduard Shevardnadze; the reformist National Democratic Party; the Georgian Popular Front, formed in 1989 to promote Georgian independence; and the Georgian Social Democratic Party, which was established in 1893 but dissolved after the Soviet takeover.

Georgia became a member of the United Nations in 1992 and joined the Commonwealth of Independent States in 1993.

Armed forces and security

In the early years of independence Georgia's armed forces were divided, but they were gradually becoming unified by the mid-1990s. The primary state military organization is the National Guard; paramilitary groups also are present. A two-year period of military service is compulsory for adult men, though draft evasion is widespread. Substantial numbers of Russian troops remain on Georgian territory.

The Ministry of Internal Affairs oversees the regular police force. Crime rates in Georgia increased after independence because of the social dislocations resulting from the conflicts in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, a lack of civil authority in parts of the country, and regional instability caused by the war in Nagorno-Karabakh.

Education

The level of education is relatively high. Tʿbilisi University was founded in 1918; the Academy of Sciences (founded 1941) is made up of several scientific institutions, which conduct research throughout the republic. Georgia has an extensive library system.

Health and welfare

Payments from public funds provide free education, medical services, pension grants, and stipend payments and free or reduced-cost accommodation in rest homes and sanatoriums, as well as holiday pay and the maintenance of kindergartens and day nurseries. Georgia ranks high in the level of medical services, and relative to other former Soviet republics its population has low incidences of tuberculosis and cancer. The republic is famed as a health centre, a reputation stemming from the numerous therapeutic mineral springs, the sunny climate of the Black Sea coast, the pure air of the mountain regions, and a wide range of resorts. The Tsqaltubo baths, with warm radon water treatment for arthritis sufferers, are especially noted.

Cultural life

Georgia is a land of ancient culture, with a literary tradition that dates to the 5th century AD. Kolkhida (Colchis) early housed a school of higher rhetoric in which Greeks as well as Georgians studied. By the 12th century, academies in Ikalto and Gelati, the first medieval higher-education centres, disseminated a wide range of knowledge. The national genius was demonstrated most clearly in Vepkhis-tqarsani (The Knight in the Panther's Skin), the epic masterpiece of the 12th-century poet Shota Rustaveli (Rustaveli, Shota). Major figures in later Georgian literary history include a famed 18th-century writer, Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani, and the novelist, poet, and dramatist Ilia Chavchavadze. The 19th-century playwright Giorgi Eristavi is regarded as the founder of the modern Georgian theatre. Among other prominent prerevolutionary authors were the lyric poet Akaki Tsereteli; Alexander Qazbegi, novelist of the Caucasus; and the nature poet Vazha Pshavela. The novelist Mikhail Javakhishvili and the poet Titsian Tabidze were executed during the Stalin era, and the poet Paolo Iashvili was censured by the government and committed suicide. Giorgi Leonidze and Galaktion Tabidze were well-known poets, and Konstantin Gamsakhurdia was celebrated for his historical novels.

The Abkhazian literary tradition dates back only to the late 19th century. Notable writers include the poet, novelist, and scholar Dmitri Gulia, the novelist and playwright Samson Chanba, the poet Bagrat Shinkuba, and Fazil Iskander, a popular satirist who writes in Russian.

Important individuals in other arts include the painters Niko Pirosmani (Pirosmanashvili), Irakli Toidze, Lado Gudiashvili, Elena Akhvlediani, and Sergo Kobuladze; the composers Zakaria Paliashvili and Meliton Balanchivadze (father of the choreographer George Balanchine); and the founder of Georgian ballet, Vakhtang Chabukiani. Georgian theatre, in which outstanding directors of the Soviet period were Kote Mardzhanishvili, Sandro Akhmeteli, and Robert Sturm, has had a marked influence in Europe and elsewhere. The Georgian film Repentance, an allegory about the repressions of the Stalin era, was directed by Tenghiz Abuladze. It won the Special Jury Prize at the 1987 Cannes Film Festival and was widely praised for its political courage.

The ancient culture of the republic is reflected in the large number of architectural monuments, including many monasteries and churches; indeed, Georgian architecture (with Armenian) played a considerable role in the development of the Byzantine style.

Georgia has a long tradition of fine metalwork. Bronze, gold, and silver objects of a high technical and aesthetic standard have been recovered from tombs of the 1st and 2nd millennia BC. Between the 10th and 13th centuries AD, Georgian goldsmiths produced masterpieces of cloisonné enamel and repoussé work, notably icons, crosses, and jewelry.

A number of newspapers and periodicals are published, most of them in Georgian. Radio programs are broadcast in Georgian and in several minority languages, and television programs are broadcast in Georgian and Russian.

History

Archaeological findings make it possible to trace the origins of human society on the territory of modern Georgia back to the early Paleolithic and Neolithic periods (Neolithic Period). A number of Neolithic sites have been excavated in the Kolkhida Lowland (Kolkhida), in the Khrami River valley in central Georgia, and in South Ossetia; they were occupied by settled tribes engaged in cattle raising and agriculture. The cultivation of grain in Georgia during the Neolithic Period is attested by finds of saddle querns (quern) and flint sickles; the earth was tilled with stone mattocks. The Caucasus was regarded in ancient times as the primeval home of metallurgy. The start of the 3rd millennium BC witnessed the beginning of Georgia's Bronze Age. Remarkable finds in Trialeti show that central Georgia was inhabited during the 2nd millennium BC by cattle-raising tribes whose chieftains were men of wealth and power. Their burial mounds have yielded finely wrought vessels in gold and silver; a few are engraved with ritual scenes suggesting Asiatic cult influence.

Origins of the Georgian nation

Early in the 1st millennium BC, the ancestors of the Georgian nation emerge in the annals of Assyria and, later, of Urartu. Among these were the Diauhi (Diaeni) nation, ancestors of the Taokhoi, who later domiciled in the southwestern Georgian province of Tao, and the Kulkha, forerunners of the Colchians, who held sway over large territories at the eastern end of the Black Sea. The fabled wealth of Colchis became known quite early to the Greeks and found symbolic expression in the legend of Medea and the Golden Fleece.

Following the influx of tribes driven from the direction of Anatolia by the Cimmerian invasion of the 7th century BC and their fusion with the aboriginal population of the Kura River valley, the centuries immediately preceding the Christian era witnessed the growth of the important kingdom of Iberia, the region that now comprises modern Kartli and Kakheti, along with Samtskhe and adjoining regions of southwestern Georgia. Colchis was colonized by Greek settlers from Miletus and subsequently fell under the sway of Mithradates VI (Mithradates VI Eupator) Eupator, king of Pontus. The campaigns of the Roman general Pompey the Great led in 66 BC to the establishment of Roman hegemony over Iberia and to direct Roman rule over Colchis and the rest of Georgia's Black Sea littoral. (See Roman Republic and Empire.)

Medieval Georgia

Georgia embraced Christianity about the year 330; its conversion is attributed to a holy captive woman, St. Nino. During the next three centuries, Georgia was involved in the conflict between Rome—and its successor state, the Byzantine Empire—and the Persian Sāsānian dynasty. Lazica on the Black Sea (incorporating the ancient Colchis) became closely bound to Byzantium. Iberia passed under Persian control, though toward the end of the 5th century a hero arose in the person of King Vakhtang Gorgaslani (Gorgasal), a ruler of legendary valour who for a time reasserted Georgia's national sovereignty. The Sāsānian monarch Khosrow I (reigned 531–579) abolished the Iberian monarchy, however. For the next three centuries, local authority was exercised by the magnates of each province, vassals successively of Persia (Iran), of Byzantium, and, after AD 654, of the Arab caliphs, who established an emirate in Tbilisi. (See Iran, ancient.)

Toward the end of the 9th century, Ashot I (the Great), of the Bagratid Dynasty, settled at Artanuji in Tao (southwestern Georgia), receiving from the Byzantine emperor the title of kuropalates (“guardian of the palace”). In due course, Ashot profited from the weakness of the Byzantine emperors and the Arab caliphs and set himself up as hereditary prince in Iberia. King Bagrat III (reigned 975–1014) later united all the principalities of eastern and western Georgia into one state. Tbilisi, however, was not recovered from the Muslims until 1122, when it fell to King David II (Aghmashenebeli, “the Builder”; reigned 1089–1125).

The zenith of Georgia's power and prestige was reached during the reign (1184–1213) of Queen Tamar, whose realm stretched from Azerbaijan to the borders of Cherkessia (now in southern Russia) and from Erzurum (in modern Turkey) to Ganja (modern Gäncä, Azerbaijan), forming a pan-Caucasian empire, with Shirvan and Trabzon as vassals and allies.

The invasions of Transcaucasia by the Mongols from 1220 onward, however, brought Georgia's golden (Golden Horde) age to an end. Eastern Georgia was reduced to vassalage under the Mongol Il-Khanid Dynasty of the line of Hülegü, while Imereti, as the land to the west of the Suram range was called, remained independent under a separate line of Bagratid rulers. There was a partial resurgence during the reign (1314–46) of King Giorgi V of Georgia, known as “the Brilliant,” but the onslaughts of the Turkic conqueror Timur between 1386 and 1403 dealt blows to Georgia's economic and cultural life from which the kingdom never recovered. The last king of united Georgia was Alexander I (1412–43), under whose sons the realm was divided into squabbling princedoms.

Turkish and Persian domination

The fall of Constantinople (modern Istanbul, Turkey) to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 isolated Georgia from western Christendom. In 1510 the Ottomans invaded Imereti and sacked the capital, Kʿutʿaisi (Kutaisi). Soon afterward, Shah Ismāʿīl I of Iran (Persia) invaded Kartli. Ivan IV (the Terrible) and other Muscovite tsars showed interest in the little Christian kingdoms of Georgia, but the Russians were powerless to stop the Muslim powers—Ṣavafid (Ṣafavid Dynasty) Iran and the Ottoman Empire, both near their zenith—from partitioning the country and oppressing its inhabitants. In 1578 the Ottomans overran the whole of Transcaucasia and seized Tbilisi, but they were subsequently driven out by Iran's Shah ʿAbbās I (reigned 1587–1629), who deported many thousands of the Christian population to distant regions of Iran. There was a period of respite under the viceroys of the house of Mukhran, who governed at Tbilisi under the aegis of the shahs from 1658 until 1723. The most notable Mukhranian ruler was Vakhtang VI, regent of Kartli from 1703 to 1711 and then king, with intervals, until 1723. Vakhtang was an eminent lawgiver and introduced the printing press to Georgia; he had the Georgian annals edited by a commission of scholars. The collapse of the Ṣafavid dynasty in 1722, however, led to a fresh Ottoman invasion of Georgia. The Ottomans were expelled by the Persian conqueror Nādir Shah (Nādir Shāh), who gave Kartli to Tʿeimuraz II (1744–62), one of the Kakhian line of the Bagratids. When Tʿeimuraz died, his son Erekle II reunited the kingdoms of Kartli and Kakheti and made a brave attempt at erecting a Caucasian multinational state based on Georgia. Imereti under King Solomon I (1752–84) succeeded in finally throwing off the domination of the declining Ottoman Empire.

Raids by Lezgian mountaineers from Dagestan, economic stringency, and other difficulties impelled Erekle to adopt a pro-Russian orientation. On July 24, 1783, he concluded with Catherine II (the Great) the Treaty of Georgievsk (Georgievsk, Treaty of), whereby Russia guaranteed Georgia's independence and territorial integrity in return for Erekle's acceptance of Russian suzerainty. Yet Georgia alone faced the Persian Āghā Moḥammad Khan (Āghā Moḥammad Khān), first of the Qājār Dynasty. Tbilisi was sacked in 1795, and Erekle died in 1798. His invalid son Giorgi XII sought to hand over the kingdom unconditionally into the care of the Russian emperor Paul, but both rulers died before this could be implemented. In 1801 Alexander I reaffirmed Paul's decision to incorporate Kartli and Kakheti into the Russian Empire. Despite the treaty of 1783, the Bagratid line was deposed and replaced by Russian military governors who deported the surviving members of the royal house and provoked several popular uprisings. Imereti was annexed in 1810, followed by Guria, Mingrelia, Svaneti, and Abkhazia in 1829, 1857, 1858, and 1864, respectively. The Black Sea ports of Potʿi and Batʿumi and areas of southwestern Georgia under Ottoman rule were taken by Russia in successive wars by 1877–78.

National revival

By waging war on the Lezgian clansmen of Dagestan and on Iran and the Ottomans, the Russians ensured the corporate survival of the Georgian nation. Under Prince Mikhail Semyonovich Vorontsov, who served with distinction as viceroy (1845–54), commerce and trade flourished. Following the liberation of the Russian serfs in 1861, the Georgian peasants also received freedom from 1864 onward, though on terms regarded as burdensome. The decay of patriarchy was accelerated by the spread of education and European influences. A railway linked Tbilisi with Potʿi from 1872, and mines, factories, and plantations were developed by Russian, Armenian, and Western entrepreneurs. Peasant discontent, the growth of an urban working class, and the deliberate policy of Russification and forced assimilation of minorities practiced by Emperor Alexander III (1881–94) fostered radical agitation among the workers and nationalism among the intelligentsia. The tsarist system permitted no organized political activity, but social issues were debated in journals, works of fiction, and local assemblies.

The leader of the national revival in Georgia was Prince Ilia Chavchavadze, leader of a literary and social movement dubbed the Pirveli Dasi, or First Group. The Meore Dasi, or Second Group, led by Giorgi Tseretʿeli, was more liberal in its convictions, but it paled before the Mesame Dasi, or Third Group, an illegal Social Democratic party founded in 1893. The Third Group professed Marxist doctrines, and from 1898 it included among its members Joseph Dzhugashvili (Stalin, Joseph), who later took the byname Joseph Stalin (Stalin, Joseph). When the Mensheviks (Menshevik)—a branch of the Russian Social-Democratic Workers Party—gained control of the group, Stalin left Georgia.

The 1905 Revolution in Russia led to widespread disturbances and guerrilla fighting in Georgia, later suppressed by Russian government Cossack troops with indiscriminate brutality. After the Russian Revolution of February 1917 (Russian Revolution of 1917) the Transcaucasian region—Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan—was ruled from Petrograd (now St. Petersburg) and known as the Ozakom. The Bolshevik coup later that year forced the predominantly Menshevik politicians of Transcaucasia to reluctantly secede from Russia and form the Transcaucasian Commissariat. The local nationalisms, combined with the pressure brought on by an Ottoman advance from the west during World War I (1914–18), brought about the breakdown of the Transcaucasian federation. On May 26, 1918, Georgia set up an independent state and placed itself under the protection of Germany, the senior partner of the Central Powers, but the victory of the Allies (Allied Powers) at the end of 1918 led to occupation of Georgia by the British. The Georgians viewed Anton Ivanovich Denikin (Denikin, Anton Ivanovich)'s counterrevolutionary White Russians, who enjoyed British support, as more dangerous than the Bolsheviks. They refused to cooperate in the effort to restore the tsarist imperial order, and British forces evacuated Batʿumi in July 1920.

Georgia's independence was recognized de facto by the Allies in January 1920, and the Russo-Georgian treaty of May 1920 briefly resulted in Soviet-Georgian cooperation.

Incorporation into the U.S.S.R. (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics)

Refused entry into the League of Nations (Nations, League of), Georgia gained de jure recognition from the Allies in January 1921. Within a month the Red Army—without Lenin's approval but under the orders of two Georgian Bolsheviks, Stalin and Grigory Konstantinovich Ordzhonikidze (Ordzhonikidze, Grigory Konstantinovich)—entered Georgia and installed a Soviet regime.

After Georgia was established as a Soviet republic, Stalin and Ordzhonikidze incorporated it into the Transcaucasian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic. The still-popular Georgian Social Democrats organized a rebellion in 1924, but it was brutally suppressed by Stalin.

During Stalin's despotic rule (1928–53), Georgia suffered from repression of all expressions of nationalism, the forced collectivization of peasant agriculture, and the purging of those communists who had led the Soviet republic in its first decade. Stalin installed his Georgian comrade Lavrenty Beria (Beria, Lavrenty Pavlovich) as party chief, first in Georgia and later over all of Transcaucasia. Even after Beria was transferred to Moscow to head the secret police, the republic was tightly controlled from the Kremlin. In the Soviet period, Georgia changed from an overwhelmingly agrarian country to a largely industrial, urban society. Meanwhile, Georgian language and literature were promoted, and a national intelligentsia grew in number and influence. After Stalin's death, a freewheeling “second economy” developed, which supplied goods and services not otherwise available.

Under the reforms of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev (Gorbachev, Mikhail) in the 1980s, Georgia moved swiftly toward independence. The former dissident Zviad Gamsakhurdia led a coalition called the Round Table to victory in parliamentary elections in October 1990. After Georgia declared independence on April 9, 1991, Gamsakhurdia was elected president. But Gamsakhurdia's policies soon drove many of his supporters into opposition, and in late 1991 civil war broke out. In January 1992 Gamsakhurdia was deposed and replaced by the Military Council, which subsequently gave power to the State Council headed by Eduard Shevardnadze (Shevardnadze, Eduard), former Soviet foreign minister and one-time first secretary of the Communist Party of Georgia. In October, 95 percent of voters elected Shevardnadze to serve as chair of the Supreme Council, Georgia's legislature, a position then tantamount to the country's president.

Independence

At the same time, secessionist movements—particularly in South Ossetia and Abkhazia—erupted in various parts of the country. In 1992 Abkhazia reinstated its 1925 constitution and declared independence, which the international community refused to recognize. In late 1993 Georgia joined the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), a loose confederation of former Soviet republics; following a cease-fire reached with Abkhazia in 1994, CIS peacekeepers were deployed to the region, although violence was ongoing. Georgia later signed an association agreement with the European Union, joined the Council of Europe (Europe, Council of) and the World Trade Organization, and became a partner in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

At the same time, secessionist movements—particularly in South Ossetia and Abkhazia—erupted in various parts of the country. In 1992 Abkhazia reinstated its 1925 constitution and declared independence, which the international community refused to recognize. In late 1993 Georgia joined the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), a loose confederation of former Soviet republics; following a cease-fire reached with Abkhazia in 1994, CIS peacekeepers were deployed to the region, although violence was ongoing. Georgia later signed an association agreement with the European Union, joined the Council of Europe (Europe, Council of) and the World Trade Organization, and became a partner in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.In 1995 a new constitution, which created a strong president, was enacted, and in November Shevardnadze was elected to that office with 75 percent of the vote, and his party, the Citizens' Union of Georgia (CUG), won 107 of the parliament's 231 seats. In legislative elections four years later, the CUG won an absolute majority, and in 2000 Shevardnadze was reelected president with nearly 80 percent of the vote. Accusations that he condoned widespread corruption and that his party engaged in rampant election fraud haunted Shevardnadze's administration. In 2003 former justice minister Mikhail Saakashvili (Saakashvili, Mikhail), the head of the National Movement party, lead a peaceable uprising—termed the “Rose Revolution”—that drove Shevardnadze from power. Saakashvili was elected president the following year and immediately opened a campaign against corruption, sought to stabilize the economy, and attempted to secure the country against ethnic strife.

Because of a pattern of human rights abuses and a growing sense of authoritarianism, the administration of President Saakashvili was shortly confronted by growing—if loosely knit—opposition. Journalists and international observers noted that the country's freedom of speech practices, though protected by law, were susceptible to influence by indirect pressure tactics, and Saakashvili's campaign against graft was criticized for its focus on the president's opposition while corrupt practices were allowed to persist among administration associates. Highly critical of the fraud and corruption he had noted among defense officials was Irakli Okruashvili, an opponent of the administration and its onetime defense minister. During his tenure Okruashvili had made public his observation of graft so widespread among armed forces officials that the army itself had fallen into a poor state of order. In 2007 he established an opposition party, Movement for United Georgia, and appeared on Imedi TV, an independent television station, to issue a number of direct accusations against President Saakashvili.

Though the statements served as a rallying point for a largely disorganized opposition, they resulted in Okruashvili's arrest on extortion charges of his own. His televised appearance a number of days later, in which he pled guilty to the charges against him and retracted his earlier accusations, was largely held by others among Saakashvili's opposition to be the result of duress; the circumstances under which he left the country following his release on bail were unclear.

These events contributed to the culmination of a number of points of criticism against Saakashvili and his once-popular government, providing opposition activists with the opportunity to arrange for massive demonstrations—thought perhaps to be as large as those that had previously brought Saakashvili to power—in Tbilisi in early November 2007. Though Saakashvili initially met the protests with several days' silence, forcible measures were soon employed in breaking up the demonstrations, and it was announced that a potential coup had been thwarted. Saakashvili's declaration of a 15-day state of emergency— criticized both locally and abroad—was quickly followed by his call for early elections in January. Though emergency rule was formally lifted a week after it had begun, Imedi TV remained off the air; ongoing demonstrations called for its return to broadcast, which finally took place approximately one month later. In late November 2007, Saakashvili resigned as president as required by law in preparation for the early elections.

In January 2008, Saakashvili was reelected, narrowly attaining the majority needed to forego a second round of voting. Although opposition groups criticized the process as flawed, the election was largely deemed free and fair by international monitors, who noted only isolated procedural violations and instances of fraud.

Meanwhile, the simmering conflict between Georgia and its breakaway regions had returned to the fore following the 2004 election of Saakashvili, who prioritized Georgian territorial unity and the reduction of ethnic strife. Although in mid-2004 Saakashvili successfully forced the leader of the autonomous republic of Ajaria from power and returned that republic to central government control, hostilities continued in the territories of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Offers by Saakashvili in 2005 to discuss autonomy for South Ossetia within the Georgian state were rejected, and in late 2006 the region reiterated its desire for independence through an unofficial referendum. The ongoing conflict also exacerbated Georgia's tense relationship with neighbouring Russia, which Georgia accused of providing support for the separatists.

Meanwhile, the simmering conflict between Georgia and its breakaway regions had returned to the fore following the 2004 election of Saakashvili, who prioritized Georgian territorial unity and the reduction of ethnic strife. Although in mid-2004 Saakashvili successfully forced the leader of the autonomous republic of Ajaria from power and returned that republic to central government control, hostilities continued in the territories of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Offers by Saakashvili in 2005 to discuss autonomy for South Ossetia within the Georgian state were rejected, and in late 2006 the region reiterated its desire for independence through an unofficial referendum. The ongoing conflict also exacerbated Georgia's tense relationship with neighbouring Russia, which Georgia accused of providing support for the separatists. In August 2008 the conflict with South Ossetia swelled sharply as Georgia engaged with local separatist fighters as well as with Russian forces that had crossed the border with the stated intent to defend Russian citizens and peacekeeping troops already in the region. In the days that followed the initial outbreak, Georgia declared a state of war as Russian forces swiftly took control of Tskhinvali, the South Ossetian capital; violence continued to spread elsewhere in the country as Russian forces also moved through the breakaway region of Abkhazia in northwestern Georgia. Georgia and Russia signed a French-brokered cease-fire that called for the withdrawal of Russian forces, but tensions continued. Russia's subsequent recognition of the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia was condemned by Georgia and met with criticism from other members of the international community. In the midst of its hostilities with Russia, Georgia announced its intention to withdraw from the CIS and called upon other member states to do likewise.

In August 2008 the conflict with South Ossetia swelled sharply as Georgia engaged with local separatist fighters as well as with Russian forces that had crossed the border with the stated intent to defend Russian citizens and peacekeeping troops already in the region. In the days that followed the initial outbreak, Georgia declared a state of war as Russian forces swiftly took control of Tskhinvali, the South Ossetian capital; violence continued to spread elsewhere in the country as Russian forces also moved through the breakaway region of Abkhazia in northwestern Georgia. Georgia and Russia signed a French-brokered cease-fire that called for the withdrawal of Russian forces, but tensions continued. Russia's subsequent recognition of the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia was condemned by Georgia and met with criticism from other members of the international community. In the midst of its hostilities with Russia, Georgia announced its intention to withdraw from the CIS and called upon other member states to do likewise. Ed.

Additional Reading

The geography, economy, culture, and history of the region are explored in Glenn E. Curtis (ed.), Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia: Country Studies (1995). Roger Rosen, The Georgian Republic (1992), is essentially a guidebook, but it provides important information on the country, its traditions, and its people. Another travel book, focusing on immediate encounters with the people of present-day Georgia, is Mary Russell, Please Don't Call It Soviet Georgia: A Journey Through a Troubled Paradise (1991). David Braund, Georgia in Antiquity: A History of Colchis and Transcaucasian Iberia, 550 BC–AD 562 (1994), chronicles the history of ancient Colchis, Iberia, and Lazica, based on current Russian and Georgian scholarship. David Marshall Lang, The Last Years of the Georgian Monarchy, 1658–1832 (1957), is a detailed study of the period in question. W.E.D. Allen, A History of the Georgian People from the Beginning Down to the Russian Conquest in the Nineteenth Century (1932, reprinted 1971), is a major study of the state and national formation, insightfully keeping in perspective the contemporary history of neighbouring states. David Marshall Lang, A Modern History of Soviet Georgia (1962, reprinted 1975), surveys the 19th century and also treats fully the impact of Russian and European ways on the Caucasian peoples. Ronald Grigor Suny, The Making of the Georgian Nation (1988), traces national formation and deals extensively with Georgia in the Soviet period.

state, United States

Introduction

Georgia, flag of

constituent state of the United States of America (United States). The largest of the U.S. states east of the Mississippi River and by many years the youngest of the 13 former English colonies, Georgia was founded in 1732, at which time its boundaries were even larger—including much of the present-day states of Alabama and Mississippi. Its landscape presents numerous contrasts, with more soil types than any other state as it sweeps from the Appalachian Mountains in the north (on the borders of Tennessee and North Carolina) to the marshes of the Atlantic coast on the southeast and the Okefenokee Swamp (which it shares with Florida) on the south. The Savannah (Savannah River) and Chattahoochee (Chattahoochee River) rivers form much of Georgia's eastern and western boundaries with South Carolina and Alabama, respectively. The capital is Atlanta.

constituent state of the United States of America (United States). The largest of the U.S. states east of the Mississippi River and by many years the youngest of the 13 former English colonies, Georgia was founded in 1732, at which time its boundaries were even larger—including much of the present-day states of Alabama and Mississippi. Its landscape presents numerous contrasts, with more soil types than any other state as it sweeps from the Appalachian Mountains in the north (on the borders of Tennessee and North Carolina) to the marshes of the Atlantic coast on the southeast and the Okefenokee Swamp (which it shares with Florida) on the south. The Savannah (Savannah River) and Chattahoochee (Chattahoochee River) rivers form much of Georgia's eastern and western boundaries with South Carolina and Alabama, respectively. The capital is Atlanta.

constituent state of the United States of America (United States). The largest of the U.S. states east of the Mississippi River and by many years the youngest of the 13 former English colonies, Georgia was founded in 1732, at which time its boundaries were even larger—including much of the present-day states of Alabama and Mississippi. Its landscape presents numerous contrasts, with more soil types than any other state as it sweeps from the Appalachian Mountains in the north (on the borders of Tennessee and North Carolina) to the marshes of the Atlantic coast on the southeast and the Okefenokee Swamp (which it shares with Florida) on the south. The Savannah (Savannah River) and Chattahoochee (Chattahoochee River) rivers form much of Georgia's eastern and western boundaries with South Carolina and Alabama, respectively. The capital is Atlanta.

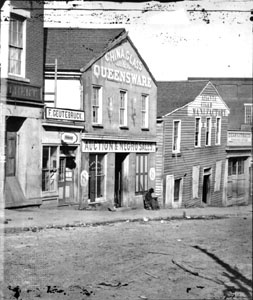

constituent state of the United States of America (United States). The largest of the U.S. states east of the Mississippi River and by many years the youngest of the 13 former English colonies, Georgia was founded in 1732, at which time its boundaries were even larger—including much of the present-day states of Alabama and Mississippi. Its landscape presents numerous contrasts, with more soil types than any other state as it sweeps from the Appalachian Mountains in the north (on the borders of Tennessee and North Carolina) to the marshes of the Atlantic coast on the southeast and the Okefenokee Swamp (which it shares with Florida) on the south. The Savannah (Savannah River) and Chattahoochee (Chattahoochee River) rivers form much of Georgia's eastern and western boundaries with South Carolina and Alabama, respectively. The capital is Atlanta.Georgia's early economy was based on the slave-plantation system. One of the first states to secede from the Union in 1861, Georgia strongly supported the Confederate States of America (Confederacy) during the American Civil War. However, it paid a high price in suffering from the devastation accompanying the Union army's siege of northern Georgia and Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman (Sherman, William Tecumseh)'s fiery capture of Atlanta in 1864. Sherman's subsequent March to the Sea laid waste a broad swath of plantation from Atlanta to Savannah—one of the first examples of total war.

At the same time that post-Civil War Georgians were romanticizing the old plantation, many were also rapidly forsaking agriculture for industry, even embracing the pro-Northern, pro-industry ideology of Atlanta journalist Henry Grady (Grady, Henry Woodfin). Subsequently, the manufacture of cotton and iron grew, but the real spur to Georgia's postwar growth was the expansion of the rail transportation system, which was centred in Atlanta.

The degree to which some of the wounds of this history have been healed in Georgia is most strikingly exemplified in contemporary Atlanta. This city was home to Martin Luther King, Jr. (King, Martin Luther, Jr.), and, for all practical purposes, it was the headquarters for the civil rights movement. In the 1960s the business community in Atlanta ensured that the kinds of racial conflicts that had damaged the reputation of other Southern cities were not repeated.

By the early 21st century the state's prosperity was based mainly in the service sector and largely in and around Atlanta, on account of that city's superior rail and air connections. Atlanta is home to the state's major utilities and to banking, food and beverage, and information technology industries and is indeed one of the country's leading locations for corporate headquarters. Propelled especially by Atlanta's progressive image and rapid economic and population growth, Georgia had by the late 20th century already pulled ahead of other states of the Deep South (South, the) in terms of overall prosperity and convergence with national socioeconomic norms. The state continues to be a leader in the southern region. Area 58,922 square miles (152,607 square km). Pop. (2000) 8,186,453; (2006 est.) 9,363,941.

Land (Georgia)

Relief

The southernmost portions of the Blue Ridge Mountains cover northeastern and north-central Georgia. In the northwest a limestone valley-and-ridge area predominates above Rome and the Coosa River. The higher elevations extend southward about 75 miles (120 km), with peaks such as Kennesaw and Stone mountains rising from the floor of the upper Piedmont. The highest point in the state, Brasstown Bald in the Blue Ridge, reaches to an elevation of 4,784 feet (1,458 metres) above sea level. Below the mountains the Piedmont extends to the fall line of the rivers—the east-to-west line of Augusta, Milledgeville, Macon, and Columbus. Along the fall region, which is nearly 100 miles (160 km) wide, sandy hills form a narrow, irregular belt. Below these hills the rolling terrain of the coastal plain levels out to the flatlands near the coast—the pine barrens of the early days—much of which are now cultivated.

The southernmost portions of the Blue Ridge Mountains cover northeastern and north-central Georgia. In the northwest a limestone valley-and-ridge area predominates above Rome and the Coosa River. The higher elevations extend southward about 75 miles (120 km), with peaks such as Kennesaw and Stone mountains rising from the floor of the upper Piedmont. The highest point in the state, Brasstown Bald in the Blue Ridge, reaches to an elevation of 4,784 feet (1,458 metres) above sea level. Below the mountains the Piedmont extends to the fall line of the rivers—the east-to-west line of Augusta, Milledgeville, Macon, and Columbus. Along the fall region, which is nearly 100 miles (160 km) wide, sandy hills form a narrow, irregular belt. Below these hills the rolling terrain of the coastal plain levels out to the flatlands near the coast—the pine barrens of the early days—much of which are now cultivated.Drainage

About half the streams of the state flow into the Atlantic Ocean, and most of the others travel through Alabama and Florida into the Gulf of Mexico (Mexico, Gulf of). A few streams in northern Georgia flow into the Tennessee River and then via the Ohio (Ohio River) and Mississippi rivers into the gulf. The river basins have not contributed significantly to the regional divisions, which have been defined more by elevations and soils. The inland waters of Georgia consist of some two dozen artificial lakes, about 70,000 small ponds created largely by the federal Soil Conservation Service, and natural lakes in the southwest near Florida. The larger lakes have fostered widespread water recreation.

About half the streams of the state flow into the Atlantic Ocean, and most of the others travel through Alabama and Florida into the Gulf of Mexico (Mexico, Gulf of). A few streams in northern Georgia flow into the Tennessee River and then via the Ohio (Ohio River) and Mississippi rivers into the gulf. The river basins have not contributed significantly to the regional divisions, which have been defined more by elevations and soils. The inland waters of Georgia consist of some two dozen artificial lakes, about 70,000 small ponds created largely by the federal Soil Conservation Service, and natural lakes in the southwest near Florida. The larger lakes have fostered widespread water recreation.Because of the region's bedrock foundation, Piedmont communities and industries must rely on surface runoff for their primary water supply. The coastal plain, underlain by alternating layers of sand, clay, and limestone, draws much of its needed water from underground aquifers. The increasing domestic and industrial use of underground water supplies in Savannah, St. Marys (Saint Mary's), and Brunswick threatens to allow brackish water to invade the aquifers serving these coastal cities.

Soils

From the coast to the fall line, sand and sandy loam predominate, gray near the coast and increasingly red with higher elevations. In the Piedmont and Appalachian regions these traits continue, with an increasing amount of clay in the soils. Land in northern Georgia is referred to as “red land” or “gray land.” In the limestone valleys and uplands in the northwest, the soils are of loam, silt, and clay and may be brown as well as gray or red.

Climate

Maritime tropical air masses dominate the climate in summer, but in other seasons continental polar air masses are not uncommon. The average January temperature in Atlanta is 42 °F (6 °C); in August it is 79 °F (26 °C). Farther south, January temperatures average 10 °F (6 °C) higher, but in August the difference is only about 3 °F (2 °C). In northern Georgia precipitation usually averages from 50 to 60 inches (1,270 to 1,524 mm) annually. The east-central areas are drier, with about 44 inches (1,118 mm). Precipitation is more evenly distributed throughout the seasons in northern Georgia, whereas the southern and coastal areas have more summer rains. Snow seldom occurs outside the mountainous northern counties.

Plant and animal life

Because of its mountains-to-the-sea topography, Georgia has a wide spectrum of natural vegetation. Trees range from maples, hemlocks, birches, and beech near Blairsville in the north to cypresses, tupelos, and red gums of the stream swamps below the fall line and to the marsh grasses of the coast and islands. Throughout most of the Appalachians, chestnuts, oaks, and yellow poplars are dominant. Much of this area is designated as national forest. The region that extends from the Tennessee border to the fall line has mostly oak and pine, with pines predominating in parts of the west. Below the fall line and outside the swamps, vast stands of pine—longleaf, loblolly, and slash—cover the landscape. Exploitation of these trees for pulpwood is a leading economic activity. Much of the land, which had at one time been cleared of trees for agriculture, has gone back to trees, scrub, and grasses.

Because of its mountains-to-the-sea topography, Georgia has a wide spectrum of natural vegetation. Trees range from maples, hemlocks, birches, and beech near Blairsville in the north to cypresses, tupelos, and red gums of the stream swamps below the fall line and to the marsh grasses of the coast and islands. Throughout most of the Appalachians, chestnuts, oaks, and yellow poplars are dominant. Much of this area is designated as national forest. The region that extends from the Tennessee border to the fall line has mostly oak and pine, with pines predominating in parts of the west. Below the fall line and outside the swamps, vast stands of pine—longleaf, loblolly, and slash—cover the landscape. Exploitation of these trees for pulpwood is a leading economic activity. Much of the land, which had at one time been cleared of trees for agriculture, has gone back to trees, scrub, and grasses. Georgia's wildlife is profuse. There are alligators in the south; bears, with a hunting season in counties near the mountains and the Okefenokee Swamp; deer, with restricted hunting in most counties; grouse; opossums; quail; rabbits; raccoons; squirrels; sea turtles, with no hunting allowed; and turkeys, with quite restricted hunting. In general, wildlife is in a period of transition. There is extensive stocking of game birds and fish. The major fish of southern Georgia, except snooks and bonefish, are in waters off the coast, and most major freshwater game fish of the United States are found in Georgia's streams and lakes. Some 20 species of plants and more than 20 species of mammals, birds, fish, and reptiles are listed as endangered in the state.

Georgia's wildlife is profuse. There are alligators in the south; bears, with a hunting season in counties near the mountains and the Okefenokee Swamp; deer, with restricted hunting in most counties; grouse; opossums; quail; rabbits; raccoons; squirrels; sea turtles, with no hunting allowed; and turkeys, with quite restricted hunting. In general, wildlife is in a period of transition. There is extensive stocking of game birds and fish. The major fish of southern Georgia, except snooks and bonefish, are in waters off the coast, and most major freshwater game fish of the United States are found in Georgia's streams and lakes. Some 20 species of plants and more than 20 species of mammals, birds, fish, and reptiles are listed as endangered in the state.People

Population (Georgia) composition

By the early 21st century Georgia was among the most populous states in the country. The population was mostly of European ancestry (white), about two-thirds, and African American, nearly one-third. A much smaller fraction of the state's residents were of Asian, Hispanic, or Native American descent. Much of the white population has deep roots in Georgia, but, compared with other states in the Deep South, such as Alabama and South Carolina, a higher percentage of the population was born outside the state. Religious affiliations are predominantly Protestant, with the Baptist and Methodist churches particularly strong within the African American community.

Settlement patterns

Georgia's settlement patterns are marked by as much variety as its physical geography. The state's indigenous population had already established a rich and complex village-based civilization by the time of European contact in the early 1500s. In the 1700s British settlement precipitated cultural conflict with the Creek (Muskogee), which intensified as white settlers moved steadily westward in the latter part of that century and into the early 1800s. One of the original English colonies and one of the first states in the union, Georgia emerged after the American Revolution as a plantation society that grew rice and cotton and depended heavily on a growing black African slave population.

During the 20th century Georgia's population gradually lost its rural character as the state's major cities expanded. In the 1980s and '90s much of the old cotton regions of the southwestern and central parts of the state continued to experience population losses; however, these losses were offset to a large extent by substantial gains in suburban Atlanta, which spread outward as far as 50 miles (80 km). The areas around Savannah and Brunswick on the Atlantic coast have also experienced rapid growth. Among the Southern states, Georgia generally has been second only to Florida in population growth since the 1970s, and its growth surpassed even that of Florida in the 1990s.

Economy

In the 20th century Georgia continued to follow its Southern neighbours in shifting from an economy that relied heavily on agriculture to one that concentrated on manufacturing and service activities. Some four-fifths of the jobs in the state are in services, including government, finance and real estate, trade, construction, transportation, and public utilities. Manufacturing accounts for many of the remaining jobs, with agriculture-related activities employing only a fraction of the workforce. In the late 20th century Georgia's economic performance surpassed that of most other states in the Deep South, and by the early 21st century Georgia's economy had become one of the strongest in the country.

Agriculture and forestry

With the continuing consolidation of farms into fewer but larger units and the advent of a pervasive agribusiness, Georgia has followed nationwide trends in agriculture that have ultimately contributed to a decrease in agriculture-related employment. The poultry industry is generally controlled by a few large companies that parcel out their work to small farmers and supply them with modern poultry-raising facilities. Cattle and swine raising are important, especially in the southern part of the state. Cash receipts from livestock and livestock products exceed those from crops. Cotton is still one of the major crops, although its value is far below the peak reached in the early 20th century. Georgia is a leading state in pecan and peanut (groundnut) production and ranks high in the production of peaches and tobacco. Corn (maize), squash, cabbage, and melons are also important crops.

Although Georgia's virgin timberlands have been cut over, the state remains among those with the most acres of commercial forestland. Lumber, plywood, and paper are major products. Georgia is the only state where pine forests are still tapped to produce naval stores.

Although Georgia's virgin timberlands have been cut over, the state remains among those with the most acres of commercial forestland. Lumber, plywood, and paper are major products. Georgia is the only state where pine forests are still tapped to produce naval stores.Resources and power

Georgia is one of the country's major producers of building stone and crushed stone, as well as cement, sand, and gravel. Pickens county in the state's northern sector has one of the richest marble deposits in the world. Georgia is also the country's prime producer of kaolin, which is taken from vast pits in the central part of the state.

The state relies primarily on fossil fuels for generation of electricity; nearly two-thirds of the state's power is derived from coal-fired thermal plants. A small but growing fraction of Georgia's power comes from natural gas. nuclear energy is also important, with two plants supplying nearly one-fourth of the state's electricity.

Manufacturing

Although manufacturing declined in Georgia in the early 21st century (following a national pattern), the sector remains an important source of employment and a significant contributor to the state's economy. Leading industries include food processing, as well as the production of textiles and apparel, paper and lumber, chemicals, plastics and rubber, automobiles, machinery, transportation equipment, and electrical and electronic supplies. The soft drink Coca-Cola originated in Atlanta in the 1880s, and the Coca-Cola Company (Coca-Cola Company, The) (one of the earliest multinational corporations) remains a major manufacturing establishment in the city. Cotton textile manufacturing has occupied a major sector of Georgia's economy since the late 19th century. The continuation of specialization in textiles (textile) is shown in the great number of rug and carpet mills in northern Georgia. While employment in the textile and apparel industries dropped in the 1980s and '90s, the state added jobs in printing and publishing and in the manufacture of industrial machinery and electronic equipment.

Services and labour

There has been massive growth in the service sector since the mid-20th century, notably in construction, retail, food and beverages, communications, information technology, and transportation. Tourism is also an important component of service activities. With its growing number of attractions, Atlanta draws the largest number of tourists each year.

Beginning in the late 1990s, new jobs were created in the state at a rate well above the national average. Most of this growth took place in the service sector and was concentrated in the Atlanta area. Georgia has also been a leader in high-technology employment.

Transportation

Water transportation determined the location of Georgia's first cities. By the late 1820s, river steamers were carrying large cargoes of cotton downstream from collecting warehouses at the fall line to Savannah and other export centres.

Railroads replaced water transport in the late 1800s and early 1900s, but more recently navigation on 500 miles (800 km) of inland waterways was revived, and a state port authority created barge service at Augusta, Columbus, Bainbridge, Savannah, and Brunswick for the distribution of chemical, wood, and mineral products. Savannah is one of the leading ports on the southern Atlantic coast, in terms of tonnage of cargo handled, and has one of the country's major container facilities.

Railroads replaced water transport in the late 1800s and early 1900s, but more recently navigation on 500 miles (800 km) of inland waterways was revived, and a state port authority created barge service at Augusta, Columbus, Bainbridge, Savannah, and Brunswick for the distribution of chemical, wood, and mineral products. Savannah is one of the leading ports on the southern Atlantic coast, in terms of tonnage of cargo handled, and has one of the country's major container facilities.Atlanta, originally called Terminus on the early railroad survey maps, had a near-optimum location for all but water transport, thus making it a hub of railroad transportation for the Southeast after the Civil War. With the advent of highways and then of air traffic, the city maintained its focal position. Three interstate highways intersect in downtown Atlanta. Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport is one of the world's busiest airports. It is also the hub of the state's aviation network, a system that includes several other airports offering commercial service.

Government and society

Constitutional framework

In 1983 Georgia ratified its 10th constitution, a document characterized by a reduction in the number of local amendments. The structure of state government limits the appointive powers of the governor, but the executive branch nonetheless exercises considerable control over state agencies by virtue of its major role in shaping the state's annual budget. The governor is elected to a four-year term but is limited to serving two terms.

In 1983 Georgia ratified its 10th constitution, a document characterized by a reduction in the number of local amendments. The structure of state government limits the appointive powers of the governor, but the executive branch nonetheless exercises considerable control over state agencies by virtue of its major role in shaping the state's annual budget. The governor is elected to a four-year term but is limited to serving two terms.The Georgia General Assembly consists of the 56-member Senate and the 180-member House of Representatives and meets annually in 40-day sessions; in 1972, districts of approximately equal population size replaced counties as units of representation. Various courts at several levels make up the state's judiciary. Probate courts, magistrate courts, and municipal courts function at the lowest level, with superior courts, state courts, and juvenile courts forming the next tier. The Court of Appeals and the Supreme Court form the capstone of the state judicial system. Judges at all levels are elected for either four- or six-year terms.

At the local level, Georgia has 159 counties, more than 500 municipalities, and hundreds of special districts (or authorities). Counties often perform municipal-type services. Independently and through multicounty cooperative districts, counties operate forestry units, airports, hospitals, and libraries. An elected board of commissioners governs most counties.

Health and welfare

Georgia has a progressive mental health program, largely the legacy of systematic reforms initiated in the early 1970s by Gov. Jimmy Carter. Regional hospitals for evaluation, emergency, and short-term treatment have been established throughout the state. In addition, there are dozens of community health care centres for outpatient treatment. A number of general hospitals have been built through federal programs. Emory University in Atlanta has nationally recognized medical research programs.

Georgia offers numerous programs in family and children's services. The Department of Public Health supports many state and regional health and development centres targeting adolescents. The state also aids colleges in training welfare workers, whose activities are supplemented by a widespread volunteer network.

Education

Public education in Georgia dates from the passage of a public school act in 1870. Since 1945 the ages for compulsory attendance have been from 6 to 15 years. The racial integration of public schools increased private-school enrollments dramatically. In 1985 the General Assembly passed the Quality Basic Education Act, which substantially revised the formula for allocating state funds to local school systems. With increased funding for schools in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, significant improvements were made in the state's education system. The state provided multiple tools and resources for teachers, systemized the instruction for problem learners, and implemented research-based practices and other progressive methodologies to advance student achievement.

Public institutions of higher learning are unified under a Board of Regents. Among the oldest and most prominent state institutions are the University of Georgia (Georgia, University of) (chartered 1785; opened 1801) in Athens, the Medical College of Georgia (chartered in 1828; became part of the university system in 1950) in Augusta, and the Georgia Institute of Technology (1885) and Georgia State University (1913), both located in Atlanta. Other public two- and four-year colleges are spread across the state so that virtually the entire population is within 35 miles (55 km) of an institution of higher learning. The undergraduate institutions (including Morehouse (Morehouse College) and Spelman (Spelman College) colleges) and the graduate and professional schools of the Atlanta University Center, all historically black institutions and together occupying a single campus, are at the forefront of African American higher education and are among the numerous private colleges in Georgia.

Cultural life

Atlanta is not only the cultural centre of Georgia but also a major cosmopolitan hub of the South. As such, it is home to numerous museums and attractions. Its Woodruff Arts Center includes the High Museum of Art (1905) and a school of the visual arts, with performing facilities for its symphony orchestra and a professional resident theatre, both of which have premiered new works. The city's Fernbank Museum of Natural History (1992) was in 2001 the first to display a specimen of Argentinosaurus, believed to be the world's largest dinosaur, and the Georgia Aquarium opened in Atlanta in 2005. Atlanta also has cooperative galleries run by painters and sculptors, and there is an active group of filmmakers.

Elsewhere in the state there are regional ballet companies and numerous community theatres. In addition to instruction in theatre, dance, the visual arts, and music in many colleges, Georgia Institute of Technology has a school of architecture, and the University of Georgia has a school of environmental design. Dozens of public museums and college galleries exhibit art, and Clark Atlanta University has a notable African American collection. In 1988 Atlanta hosted the first National Black Arts Festival, a major annual event that has continued into the 21st century.

Georgia is rich in traditional arts and crafts, especially in the mountainous north. The craft of tufted fabrics was a major factor in attracting the carpet industry that developed around Dalton. A mountain arts cooperative has a store in Tallulah Falls, and craft shops are attached to several art galleries. Country music conventions are held in northern Georgia—with some tension between purists and users of electronic equipment. In rural churches of northwestern Georgia, unaccompanied singing from the Sacred Harp shape-note hymnal remains strong, and throughout the area many prayers and sermons are delivered melodically.

The state has produced some of the best-known figures in American popular music. Ray Charles (Charles, Ray) helped forge soul music from rhythm and blues, jazz, and gospel, and his hit rendition of "Georgia on My Mind" helped establish it as the state song. Little Richard was one of the early stars of rock and roll (rock), and the Allman Brothers Band (Allman Brothers Band, the) pioneered the Southern rock genre. Gladys Knight and the Pips (Knight, Gladys, and the Pips) recorded numerous chart-topping songs in the 1960s and '70s that have become soul and rhythm-and-blues standards.