whaling

Introduction

the hunting of whales (whale) for food and oil. Whaling was once conducted around the world by seafaring nations in pursuit of the giant animals that seemed as limitless as the oceans in which they swam. However, since the mid-20th century, when whale populations began to drop catastrophically, whaling has been conducted on a very limited scale. It is now the subject of great scrutiny, both by formal regulatory bodies and by nongovernmental organizations.

the hunting of whales (whale) for food and oil. Whaling was once conducted around the world by seafaring nations in pursuit of the giant animals that seemed as limitless as the oceans in which they swam. However, since the mid-20th century, when whale populations began to drop catastrophically, whaling has been conducted on a very limited scale. It is now the subject of great scrutiny, both by formal regulatory bodies and by nongovernmental organizations.Whaling has been documented in many sources—from Neolithic (Neolithic Period) cave art to present-day annual reports of the International Whaling Commission—but there is no firm proof as to what people first engaged in the practice. Prehistoric inhabitants of far northern coastal regions, lacking adequate agriculture, developed successful whaling techniques using Stone Age weapons. By the time the (Eskimo) of eastern and western North America were first encountered by Europeans, they had already mastered whale hunting, and many Inuit methods were used as recently as 1900. For the Inuit, a captured whale supplied food, fuel, and light; sinews provided cordage, and bones were used for tools and construction. Not until the 20th century, when floating factory ships (factory ship) came into use, did other civilizations succeed in the same efficient use of the whole carcass. Elsewhere, from the first intensive hunting of whales in the early 17th century to the early 20th century, little more than blubber and baleen (baleen whale) was used, and the remainder of the animal was discarded. Each successive discovery of new whaling grounds resulted in the near disappearance of a particular species. The efficiency of modern hunting methods hastened this trend to the point that the industry has all but taken its place in history, leaving only a few enterprises to carry on in a limited fashion.

The history of whaling

International whaling developed in stages that were determined by changing demand, diminishing stocks, and advancing technology. A lengthy primitive stage eventually led to commercial whaling; new markets and technical and chemical advances then produced modern whaling, which led to virtual extinction of the quarry and a return to a primitive stage. The commercial stages were dominated overwhelmingly by northern Europeans and Americans (United States)—first the Dutch, then the British (United Kingdom) and Americans, and finally the Norwegians and British. Only at the very end, when Europeans no longer found the trade profitable, did they surrender the remaining whales to the Russians and Japanese.

Primitive whaling

Archaeological evidence suggests that primitive whaling was practiced by the Inuit and others in the North Atlantic and North Pacific by 3000 BC, and it continues in a number of remote cultures to the present. The quarry has always been small, easily beached whales, such as belugas (beluga) and narwhals (narwhal), or larger species that would come close to shore to breed in sheltered bays. The Japanese used nets, and the Aleuts (Aleut) used poisoned spears. The Inuit successfully hunted large whales from skin boats, employing toggle-head harpoons (harpoon) attached by hide ropes to inflated sealskin floats. A number of harpoons were darted into a whale, impeding its escape until a safe kill could be made with a lance. In Europe, Nordic people hunted small whales, and in Iceland laws addressed whaling in the 13th century.

The forerunners of commercial whaling were the Basques (Basque), who caught northern right whales (right whale) as they gathered to breed in the Bay of Biscay (Biscay, Bay of). Docile, slow-moving, and sleeping on the surface, the whales were chased by rowboat, struck by harpoon, “played” like fish, and then lanced. Their bodies, which floated after death, were towed to shore for stripping and boiling of the thick blubber and processing of the baleen. When seaworthy oceangoing ships were built, Basques set off in search of other whaling bays and found them—perhaps as early as the 14th century and certainly by the 16th—across the Atlantic off the coast of southern Labrador.

Early commercial whaling

While the Basques acquired experience, northern Europeans developed more capital and better markets. Drafting Basque whalemen for Arctic explorations, the English Muscovy Company initiated the exploitation of whaling bays around the island of Spitsbergen in 1610. The Dutch (Netherlands, The) followed immediately and, with a combination of violence and better business organization, broke the English monopoly, which had already stifled competition. Smeerenburg (“Blubbertown”) was built on Spitsbergen after 1619. In its heyday during the 1630s and '40s, Smeerenburg had 150 men servicing whalers that hunted the Greenland right, or bowhead, whale in the surrounding Arctic Ocean.

The demise of Arctic bay whaling in the mid-1650s owed less to overfishing than to a miniature ice age that lasted for the rest of the 17th century. Smeerenburg shut down in the 1660s, although Dutch and German whalers navigated the open-sea ice. Whales were flensed (stripped) alongside the vessels, and their blubber, preserved to some extent by the cold, was taken home in barrels. This Greenland phase of whaling extended into the Davis Strait after 1719 and was dominated by the Dutch and Germans until the 1780s, when Britain forged ahead in order to service its industrial revolution.

Since the 1690s the British had pursued extensive “fishing” from bay stations in the North American colonies, and Cape Cod (Cod, Cape), Long Island, and Rhode Island became new centres of activity. There a new type of whaling was inaugurated in 1712, when a Nantucket vessel caught the first sperm whale, whose waxy oil (sperm oil) and spermaceti were worth far more than right whale oil. Sperm whales are smaller than right whales and are pelagic, living in the open ocean. Sperm whaling lured expeditions into warmer waters, where rapid putrefaction of blubber was overcome in midcentury by the introduction of onboard rendering. Henceforth, voyages were limited only by the whaler's capacity and the crew's endurance. Hunts extended into the whale-rich seas of the Pacific, and four-year cruises became common, often mixing pelagic whaling with sealing and bay whaling for right whales. This vanguard incidentally opened the Pacific to British and American explorations and annexations.

During the 18th and early 19th centuries, whaling vessels were chiefly merchant ships (occasionally barks (bark)) transporting equipment, crews, and catch. They were double-hulled and reinforced with beams against sea ice and were heavily armed against attack. Displacing 250–350 tons, these vessels were two or three times the tonnage of the average merchant ship for the sake of cargo capacity. Three tiers of barrels could be crammed below deck, while crews berthed on the half deck. American whaling ships were initially smaller than British vessels and were painted to look like warships. During the 19th century purpose-built barks measuring 30–45 metres (100–150 feet) and displacing 300–400 tons became more common, and in the 1850s clipper ships (clipper ship) gained favour.

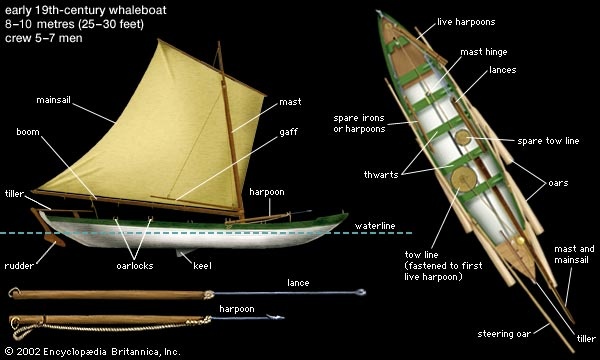

During the 18th and early 19th centuries, whaling vessels were chiefly merchant ships (occasionally barks (bark)) transporting equipment, crews, and catch. They were double-hulled and reinforced with beams against sea ice and were heavily armed against attack. Displacing 250–350 tons, these vessels were two or three times the tonnage of the average merchant ship for the sake of cargo capacity. Three tiers of barrels could be crammed below deck, while crews berthed on the half deck. American whaling ships were initially smaller than British vessels and were painted to look like warships. During the 19th century purpose-built barks measuring 30–45 metres (100–150 feet) and displacing 300–400 tons became more common, and in the 1850s clipper ships (clipper ship) gained favour. Throughout this period, catching was by hand-thrown harpoon from double-ended boats carrying five to seven men. The boats usually measured seven to nine metres long, and in America they were made of half-inch cedar planks. European Arctic boats were stronger, carver-built craft with oak frames and three-quarter-inch fir planking. Harpooners and boatsteerers were the key men when the strike was made. After the harpoon hit its mark, the whale was “played” at the end of ropes and killed by lance when exhausted. The catch was then towed to the whaler, where blubber and baleen were cut away by men either working from fragile platforms or walking with spiked boots directly upon the carcass. Finally, what was left of the animal was winched on deck for cutting, casking, and carrying home. (For a contemporaneous description of the methods used by 18th-century whalemen, see the Britannica Classic, Whale Fishery.) From about 1760 onward, sperm whales were rendered in “try-works”—a pair of very large cast-iron pots (try-pots) on a water-filled brick structure approximately two by three metres situated near the forward hatch. The only other technical innovation of this period—the harpoon gun—was introduced around 1800 but proved to be a failure.

Throughout this period, catching was by hand-thrown harpoon from double-ended boats carrying five to seven men. The boats usually measured seven to nine metres long, and in America they were made of half-inch cedar planks. European Arctic boats were stronger, carver-built craft with oak frames and three-quarter-inch fir planking. Harpooners and boatsteerers were the key men when the strike was made. After the harpoon hit its mark, the whale was “played” at the end of ropes and killed by lance when exhausted. The catch was then towed to the whaler, where blubber and baleen were cut away by men either working from fragile platforms or walking with spiked boots directly upon the carcass. Finally, what was left of the animal was winched on deck for cutting, casking, and carrying home. (For a contemporaneous description of the methods used by 18th-century whalemen, see the Britannica Classic, Whale Fishery.) From about 1760 onward, sperm whales were rendered in “try-works”—a pair of very large cast-iron pots (try-pots) on a water-filled brick structure approximately two by three metres situated near the forward hatch. The only other technical innovation of this period—the harpoon gun—was introduced around 1800 but proved to be a failure.Both northern and southern whaling entered the doldrums about 1860. The U.S. fleet of over 700 vessels ( New Bedford alone registered 429 in 1857) declined rapidly, owing principally to the discovery in Pennsylvania of petroleum (1859), which replaced sperm oil and spermaceti candles. The British Arctic fleet was devastated in the 1830s and '40s by overfishing and frozen seas. The introduction of whale-product substitutes, such as vegetable oil, steel-boned corsets, and gas lamps, was partially offset by rising industrial demand. Residual whaling activity continued in the South Pacific and the Davis Strait until about 1914, and the taking of North Pacific right whales from San Francisco continued into the 1920s.

Modern whaling

Although right whales were on the verge of extinction, neither Britain nor America could catch the vast stocks of “wrong” whales, the rorquals (rorqual) (chiefly the blue (blue whale), humpback (humpback whale), fin (fin whale), and sei whales (sei whale)). With top speeds of 30–50 km (20–30 miles) per hour, these cetaceans (cetacean) were too fast and too heavy; they also sank after dying. The American Thomas Roys employed innovations such as the rocket harpoon during the 1860s, but these were of limited success. A Norwegian, Svend Foyn, brought whaling into the modern age with the construction of his 86-ton, seven-knot Spes et Fides, the first steam-powered whale catcher. Generating only 50 horsepower, it relied on stealth and various new technologies, including Foyn's newly invented harpoon cannon. This forward-mounted, muzzle-loading gun fired a heavy harpoon that would bend without breaking, the head of which was equipped with a time-delay grenade to damage vital organs or cause massive bleeding. Power from the main engines could be diverted to playing, raising, and towing whales for processing ashore. Carcasses were inflated with compressed air (another Foyn innovation) so that they would float while awaiting collection. Although the flesh and oil were fresh enough for human consumption, rapid processing was essential. At the shore station, whales were winched up a slipway to a platform where blubber was peeled off, cut up, and boiled. Bones were sawed up and boiled with inedible meat for low-grade oil, and the residue was dried and ground for fertilizer or animal feed. “Total carcass utilization” became a slogan of the leading companies.

Foyn's success led to the establishment of other shore stations in Norway, Scotland, and Newfoundland. Near the turn of the century, demand for whale oil suddenly increased as soap and margarine production ran ahead of fat supplies, and Normann's hydrogenation process enabled the transformation of oil into fat. Norwegian and British shore stations opened in the Antarctic, South America, and South Africa, and catches rose from approximately 2,000 to more than 20,000 per year in the first decade of the 20th century. By 1909 pelagic whaling had begun in Antarctic waters, and further technological innovations were required.

Starting just before World War I, the gradual shift from shore stations to floating factories was to be the most significant development in the history of whaling. Floating factories steamed into previously unreachable waters, servicing their catchers, processing whales, and transferring oil and meat to tankers and cargo vessels (which also brought fuel oil) for timely shipment to market. Factory ships (factory ship) were all converted merchant vessels until 1929, when various specialized designs starting at 1,500 tons were realized. Early versions averaged 6,500 tons, followed by 11,000–25,000-ton craft, though optimum size became 16,000 tons. These ships had the ability to bring 100-ton rorquals on board—a feat first accomplished in 1925 by installation of a slipway through the stern. Powerful winches and a “claw” fastened around the whale's tail were used to haul the animal from the water to an open butchering deck, or “plan,” where it was rapidly dismembered to release heat and prevent putrefaction. Rendering then proceeded as in land stations, although spatial constraints required that specific equipment be developed for floating factories: butchering machinery was compact; water condensing plants were introduced; and, above all, the “tween-decks” Hartmann high-pressure cookers were developed. Loaded with whale flesh through deck hatches, the cookers were the linchpin of a system allowing a 100-ton blue whale to be disposed of in an hour while greatly improving the yield of premium oil.

Guns were also improved. Breechloaders were introduced in 1924, and in the 1960s, after much trial and error, electric harpoons that caused instant death were introduced to save pain and raise meat quality. Radio communication was used extensively, and airplanes (later helicopters) were employed to spot whales. But the most obvious improvement was the “gunner's bridge,” introduced in the 1925–26 whaling season, by which the harpooner-master could rush from the bridge to an elevated gun at the bow.

Although Britain produced much capital and commercial organization, Norway dominated this period of rapidly rising oil production. Many of the expeditions and improvements (and almost all the crewmen) were of Norwegian origin. By 1930 these predominantly pelagic efforts were supported by 6 shore stations, 41 factory ships, and 232 catchers in the Antarctic. Whaling flourished elsewhere but was relatively unimportant in comparison.

As larger floating factories accelerated processing, there was pressure to improve catching, and during the 1930s the number of catchers per factory rose from four to eight. Catchers became progressively larger and faster and finally were able to overtake swimming rorquals regularly. The Japanese (Japan) developed diesel engines, and boats equipped with these engines generated 2,500 horsepower while displacing only 600 tons. Although they were very noisy, their lack of stealth was more than compensated for by greater speed and maneuverability. Such efficiency, however, greatly increased fuel consumption and running costs and ultimately led to economic problems and reckless overfishing.

As larger floating factories accelerated processing, there was pressure to improve catching, and during the 1930s the number of catchers per factory rose from four to eight. Catchers became progressively larger and faster and finally were able to overtake swimming rorquals regularly. The Japanese (Japan) developed diesel engines, and boats equipped with these engines generated 2,500 horsepower while displacing only 600 tons. Although they were very noisy, their lack of stealth was more than compensated for by greater speed and maneuverability. Such efficiency, however, greatly increased fuel consumption and running costs and ultimately led to economic problems and reckless overfishing.After World War II (during which 27 floating factories were sunk), whale oil was so important to the fat rations of Europe, and meat to Japan and Russia (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics), that a wave of newer, larger factories (up to 32,000 tons) were built, as were 18-knot diesel-powered catchers. British and Norwegian companies controlled greater than 80 percent of the trade from 1945 to 1950, and their success attracted other states to whaling—most notably The Netherlands, the Soviet Union, and Japan. Progressively smaller whales were taken as overfishing decimated first the blue whale population in the 1940s, the fin and humpback whales between 1955 and 1970, and the sei whale thereafter. Whaling shifted from the Antarctic (where some 1.4 million whales had been killed) to the North Pacific. A renewed attack on the sperm whale took place in the 1950s when new uses were found for its oil.

With no more concentrations of large whales remaining, European companies withdrew after the 1962–63 season, leaving whaling chiefly to the Soviets and the Japanese. Soviet enterprises were subsidized, and modern refrigeration allowed the Japanese to make a valuable delicacy out of the meat. But even this whaling was doomed as it rapidly depleted the last of the “commercial” whales. No factories sailed after 1978, and by the 1980s the international whale trade was dead, although small-scale coastal whaling continued.

With no more concentrations of large whales remaining, European companies withdrew after the 1962–63 season, leaving whaling chiefly to the Soviets and the Japanese. Soviet enterprises were subsidized, and modern refrigeration allowed the Japanese to make a valuable delicacy out of the meat. But even this whaling was doomed as it rapidly depleted the last of the “commercial” whales. No factories sailed after 1978, and by the 1980s the international whale trade was dead, although small-scale coastal whaling continued.Regulation

The demise of whales and whaling was regularly forecast in the 1930s. The major states and companies involved introduced their own controls, but restraint was hampered by the selfishness of commerce and the ignorance of science. In 1931 the League of Nations (Nations, League of) organized an International Whaling Convention, but this had little success in leading the way toward restrictive regulations. The International Whaling Commission (IWC) was established in 1946 to conserve whale stocks. It prohibited the killing of right and gray whales (gray whale) and limited the annual Antarctic kill to 15,000 Blue Whale Units (BWU; 1 BWU = 2 fin, 2.5 humpback, or 6 sei whales). The commission created closed areas and closed seasons around the world, but enforcement was difficult, and the BWU standard was overoptimistic about total and optimum whale stocks. Eventually, scientific pressure coinciding with commercial crisis resulted in the downward adjustment of the BWU limit to 2,300 by 1962. Soon afterward, two additional species were protected: the humpback whale (1963) and the blue whale (1965). In 1972 the United Nations voted in vain for a moratorium on whaling, but instead the BWU was replaced with quotas for each of the other species. In 1979 the use of floating factories was banned except for minke whales. Finally, to protect remaining stocks and allow time for detailed research, a moratorium on all commercial whaling during the 1986–90 seasons was agreed to by members of the IWC. It remains in force. However, some residual Japanese and Norwegian whaling continues, often under the guise of scientific research.

The demise of whales and whaling was regularly forecast in the 1930s. The major states and companies involved introduced their own controls, but restraint was hampered by the selfishness of commerce and the ignorance of science. In 1931 the League of Nations (Nations, League of) organized an International Whaling Convention, but this had little success in leading the way toward restrictive regulations. The International Whaling Commission (IWC) was established in 1946 to conserve whale stocks. It prohibited the killing of right and gray whales (gray whale) and limited the annual Antarctic kill to 15,000 Blue Whale Units (BWU; 1 BWU = 2 fin, 2.5 humpback, or 6 sei whales). The commission created closed areas and closed seasons around the world, but enforcement was difficult, and the BWU standard was overoptimistic about total and optimum whale stocks. Eventually, scientific pressure coinciding with commercial crisis resulted in the downward adjustment of the BWU limit to 2,300 by 1962. Soon afterward, two additional species were protected: the humpback whale (1963) and the blue whale (1965). In 1972 the United Nations voted in vain for a moratorium on whaling, but instead the BWU was replaced with quotas for each of the other species. In 1979 the use of floating factories was banned except for minke whales. Finally, to protect remaining stocks and allow time for detailed research, a moratorium on all commercial whaling during the 1986–90 seasons was agreed to by members of the IWC. It remains in force. However, some residual Japanese and Norwegian whaling continues, often under the guise of scientific research.The IWC allows some cultural whaling: minke and fin whales are taken by Greenlanders, gray whales by Russians, and right whales by Native Americans. Only the last poses any threat to the species, and growing numbers of smaller whales have in recent years encouraged calls for the reintroduction of whaling for “meat” species such as minke and pilot whales (pilot whale). Such suggestions are met by fervent opposition from preservation groups, but the demand for whale meat is so great that coastal whaling may be resumed. This prospect has raised the idea, even among some antiwhaling groups, that the best way to conserve whales may be to allow carefully monitored whaling within IWC regulations rather than provoking a free-for-all outside the commission. In either case, limited whaling seems likely to return under a very strictly monitored regime.

Whale products

Most, but not all, economic products derived from whales over the centuries have been rendered obsolete by other materials. Some, such as lubricants based on whale oil and sperm oil, whereas others, such as baleen, spermaceti, and sperm whale teeth (the raw material used in the art of scrimshaw), were mainly utilized prior to the 20th century. Sperm whales were also the source of ambergris, a waxy substance that was highly prized for use in perfumes. Whale meat was of no value in early commercial whaling because it putrefied quickly. Modern operations, however, produced meat meal for animal consumption or fertilizer, and in the late 1940s refrigerated ships facilitated recovery of edible meat. Most countries have rejected whale meat for human consumption, but it has long been popular in Japan, where its high value supported the last phase of commercial whaling.

Additional Reading

Recent books on the practice and history of whaling include Richard Ellis, Men and Whales (1991, reissued 1999), a comprehensive treatment with chapters arranged chronologically and geographically. Relationships between opposing sides of current whaling issues are examined in Peter J. Stoett, The International Politics of Whaling (1997), which includes a chronology of whaling. Gordon Jackson, The British Whaling Trade (1978), explores the international and economic context of whaling. Commercial whaling statistics since 1930 are contained in serial volumes of International Whaling Statistics.The standard work on modern whaling remains an abridged English translation of J.N. Tønnessen and A.O. Johnsen, The History of Modern Whaling (1982; originally published in Norwegian in 4 vol., 1959–70). Other works devoted to more specific segments of the trade are Lance E. Davis, Robert E. Gallman, and Karin Gleiter, In Pursuit of Leviathan: Technology, Institutions, Productivity, and Profits in American Whaling, 1816–1906 (1997), which analyzes the economic factors underlying the rise and fall of American whaling, including technology of whaling vessels; Briton Cooper Busch, Whaling Will Never Do for Me: The American Whaleman in the Nineteenth Century (1994), which covers the social history of whaling; Granville Allen Mawer, Ahab's Trade: The Saga of South Seas Whaling (1999), which includes excerpts from a wide variety of historical documents; Harry Morton, The Whale's Wake (1982), which relates whaling to the European occupation of the South Pacific; John R. Bockstoce, Whales, Ice, and Men: The History of Whaling in the Western Arctic (1986, reprinted with corrections 1995), which traces the history of whaling in the North Pacific from the mid-18th to the early 20th century; and E.J. Slijper, Whales, trans. from Dutch, 2nd ed., edited by Richard J. Harrison (1979), which presents a European viewpoint of whaling.A much earlier yet still modern survey is provided by J.T. Jenkins, A History of the Whale Fisheries: From the Basque Fisheries of the Tenth Century to the Hunting of the Finner Whale at the Present Date (1921, reprinted 1971). Nineteenth-century descriptions of whaling include W. Scoresby, An Account of the Arctic Regions, with a History and Description of the Northern Whale-Fishery, 2 vol. (1820, reprinted 1969); and Alexander Starbuck, History of the American Whale Fishery from Its Earliest Inception to the Year 1876 (1878, reissued 1989), featuring a list of all known voyages of 1715–1876.