Iraq War

2003

Introduction

also called Second Persian Gulf War

conflict in Iraq beginning in 2003 and consisting of two phases. The first of these was a brief, conventionally fought war (March–April 2003), in which a combined force of troops from the United States and Great Britain (with smaller contingents from several other countries) invaded Iraq and rapidly defeated Iraqi military and paramilitary forces. It was followed by a longer second phase in which a U.S.-led occupation of Iraq was opposed by an increasingly intensive armed insurgency.

conflict in Iraq beginning in 2003 and consisting of two phases. The first of these was a brief, conventionally fought war (March–April 2003), in which a combined force of troops from the United States and Great Britain (with smaller contingents from several other countries) invaded Iraq and rapidly defeated Iraqi military and paramilitary forces. It was followed by a longer second phase in which a U.S.-led occupation of Iraq was opposed by an increasingly intensive armed insurgency.Prelude to war

Iraq's invasion of Kuwait in 1990 ended in Iraq's defeat by a U.S.-led coalition in the Persian Gulf War (1990–91). However, the Iraqi branch of the Baʿth Party, headed by Ṣaddām Ḥussein, managed to retain power by harshly suppressing uprisings of the country's minority Kurds (Kurd) and its majority Shīʿite Arabs. To stem the exodus of Kurds from Iraq, the allies established a “safe haven” in northern Iraq's predominantly Kurdish regions, and allied warplanes patrolled “no-fly” zones in northern and southern Iraq that were off-limits to Iraqi aircraft. Moreover, to restrain future Iraqi aggression, the United Nations (UN) implemented economic sanctions (sanction) against Iraq in order to, among other things, hinder the progress of its most lethal arms programs, including those for the development of nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons (weapon of mass destruction). (See weapon of mass destruction.) UN inspections during the mid-1990s uncovered a variety of proscribed weapons and prohibited technology throughout Iraq. That country's continued flouting of the UN weapons ban and its repeated interference with the inspections frustrated the international community and led U.S. Pres. Bill Clinton (Clinton, Bill) in 1998 to order the bombing of several Iraqi military installations (code-named Operation Desert Fox). After the bombing, however, Iraq refused to allow inspectors to reenter the country, and during the next several years the economic sanctions slowly began to erode as neighbouring countries sought to reopen trade with Iraq.

In 2002 the new U.S. president, George W. Bush (Bush, George W.), argued that the vulnerability of the United States following the September 11 attacks of 2001, combined with Iraq's alleged continued possession and manufacture of weapons of mass destruction (an accusation that was later proved erroneous) and its support for terrorist groups—which, according to the Bush administration, included al-Qaeda (Qaeda, al-), the perpetrators of the September 11 attacks—made disarming Iraq a renewed priority. UN Security Council (Security Council, United Nations) Resolution 1441, passed on Nov. 8, 2002, demanded that Iraq readmit inspectors and that it comply with all previous resolutions. Iraq appeared to comply with the resolution, but in early 2003 President Bush and British Prime Minister Tony Blair (Blair, Tony) declared that Iraq was actually continuing to hinder UN inspections and that it still retained proscribed weapons. Other world leaders, such as French Pres. Jacques Chirac (Chirac, Jacques) and German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder (Schröder, Gerhard), citing what they believed to be increased Iraqi cooperation, sought to extend inspections and give Iraq more time to comply with them. However, on March 17, seeking no further UN resolutions and deeming further diplomatic efforts by the Security Council futile, Bush declared an end to diplomacy and issued an ultimatum to Ṣaddām, giving the Iraqi president 48 hours to leave Iraq. The leaders of France, Germany, Russia, and other countries objected to this buildup toward war.

In 2002 the new U.S. president, George W. Bush (Bush, George W.), argued that the vulnerability of the United States following the September 11 attacks of 2001, combined with Iraq's alleged continued possession and manufacture of weapons of mass destruction (an accusation that was later proved erroneous) and its support for terrorist groups—which, according to the Bush administration, included al-Qaeda (Qaeda, al-), the perpetrators of the September 11 attacks—made disarming Iraq a renewed priority. UN Security Council (Security Council, United Nations) Resolution 1441, passed on Nov. 8, 2002, demanded that Iraq readmit inspectors and that it comply with all previous resolutions. Iraq appeared to comply with the resolution, but in early 2003 President Bush and British Prime Minister Tony Blair (Blair, Tony) declared that Iraq was actually continuing to hinder UN inspections and that it still retained proscribed weapons. Other world leaders, such as French Pres. Jacques Chirac (Chirac, Jacques) and German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder (Schröder, Gerhard), citing what they believed to be increased Iraqi cooperation, sought to extend inspections and give Iraq more time to comply with them. However, on March 17, seeking no further UN resolutions and deeming further diplomatic efforts by the Security Council futile, Bush declared an end to diplomacy and issued an ultimatum to Ṣaddām, giving the Iraqi president 48 hours to leave Iraq. The leaders of France, Germany, Russia, and other countries objected to this buildup toward war.The 2003 conflict

When Ṣaddām refused to leave Iraq, U.S. and allied forces launched an attack on the morning of March 20; it began when U.S. aircraft dropped several precision-guided bombs on a bunker complex in which the Iraqi president was believed to be meeting with senior staff. This was followed by a series of air strikes directed against government and military installations, and within days U.S. forces had invaded Iraq from Kuwait in the south (U.S. Special Forces had previously been deployed to Kurdish-controlled areas in the north). Despite fears that Iraqi forces would engage in a scorched-earth policy—destroying bridges and dams and setting fire to Iraq's southern oil wells—little damage was done by retreating Iraqi forces; in fact, large numbers of Iraqi troops simply chose not to resist the advance of coalition forces. In southern Iraq the greatest resistance to U.S. forces as they advanced northward was from irregular groups of Baʿth Party supporters, known as Ṣaddām's Fedayeen. British forces—which had deployed around the southern city of Al-Baṣrah (Basra)—faced similar resistance from paramilitary and irregular fighters.

When Ṣaddām refused to leave Iraq, U.S. and allied forces launched an attack on the morning of March 20; it began when U.S. aircraft dropped several precision-guided bombs on a bunker complex in which the Iraqi president was believed to be meeting with senior staff. This was followed by a series of air strikes directed against government and military installations, and within days U.S. forces had invaded Iraq from Kuwait in the south (U.S. Special Forces had previously been deployed to Kurdish-controlled areas in the north). Despite fears that Iraqi forces would engage in a scorched-earth policy—destroying bridges and dams and setting fire to Iraq's southern oil wells—little damage was done by retreating Iraqi forces; in fact, large numbers of Iraqi troops simply chose not to resist the advance of coalition forces. In southern Iraq the greatest resistance to U.S. forces as they advanced northward was from irregular groups of Baʿth Party supporters, known as Ṣaddām's Fedayeen. British forces—which had deployed around the southern city of Al-Baṣrah (Basra)—faced similar resistance from paramilitary and irregular fighters.In central Iraq units of the Republican Guard—a heavily armed paramilitary group connected with the ruling party—were deployed to defend the capital of Baghdad. As U.S. Army and Marine forces advanced northwestward up the Tigris-Euphrates river valley, they bypassed many populated areas where Fedayeen resistance was strongest and were slowed only on March 25 when inclement weather and an extended supply line briefly forced them to halt their advance within 60 miles (95 km) of Baghdad. During the pause, U.S. aircraft inflicted heavy damage on Republican Guard units around the capital. U.S. forces resumed their advance within a week, and on April 4 they took control of Baghdad's international airport. Iraqi resistance, though at times vigorous, was highly disorganized, and over the next several days army and Marine Corps units staged raids into the heart of the city. On April 9 resistance in Baghdad collapsed, and U.S. soldiers took control of the city.

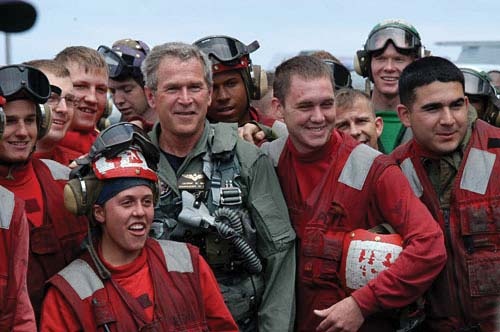

On that same day Al-Baṣrah was finally secured by British forces, which had entered the city several days earlier. In the north, however, plans to open up another major front had been frustrated when the Turkish government refused to allow mechanized and armoured U.S. Army units to pass through Turkey to deploy in northern Iraq. Regardless, a regiment of American paratroopers did drop into the area, and U.S. Special Forces soldiers joined with Kurdish peshmerga fighters to seize the northern cities of Kirkuk on April 10 and Mosul on April 11. Ṣaddām's hometown of Tikrīt, the last major stronghold of the regime, fell with little resistance on April 13. Isolated groups of regime loyalists continued to fight on subsequent days, but the U.S. president declared an end to major combat on May 1. Iraqi leaders fled into hiding and were the object of an intense search by U.S. forces. Ṣaddām Ḥussein was captured on Dec. 13, 2003, and was turned over to Iraqi authorities in June 2004 to stand trial for various crimes; he was subsequently convicted of crimes against humanity and was executed on Dec. 30, 2006.

On that same day Al-Baṣrah was finally secured by British forces, which had entered the city several days earlier. In the north, however, plans to open up another major front had been frustrated when the Turkish government refused to allow mechanized and armoured U.S. Army units to pass through Turkey to deploy in northern Iraq. Regardless, a regiment of American paratroopers did drop into the area, and U.S. Special Forces soldiers joined with Kurdish peshmerga fighters to seize the northern cities of Kirkuk on April 10 and Mosul on April 11. Ṣaddām's hometown of Tikrīt, the last major stronghold of the regime, fell with little resistance on April 13. Isolated groups of regime loyalists continued to fight on subsequent days, but the U.S. president declared an end to major combat on May 1. Iraqi leaders fled into hiding and were the object of an intense search by U.S. forces. Ṣaddām Ḥussein was captured on Dec. 13, 2003, and was turned over to Iraqi authorities in June 2004 to stand trial for various crimes; he was subsequently convicted of crimes against humanity and was executed on Dec. 30, 2006.Occupation and continued warfare

Following the collapse of the Baʿthist regime, Iraq's major cities erupted in a wave of looting that was directed mostly at government offices and other public institutions, and there were severe outbreaks of violence—both common criminal violence and acts of reprisal against the former ruling clique. Restoring law and order was one of the most arduous tasks for the occupying forces, one that was exacerbated by continued attacks against occupying troops that soon developed into full-scale guerrilla warfare; increasingly, the conflict came to be identified as a civil war, although the Bush administration generally avoided using that term and instead preferred the label “sectarian violence.” Coalition casualties had been light in the initial 2003 combat, with about 150 deaths by May 1. However, deaths of U.S. troops soared thereafter, reaching some 1,000 by the time of the U.S. presidential election in November 2004 and surpassing 3,000 in early 2007; in addition, several hundred soldiers from other coalition countries have been killed. The number of Iraqis who died during the conflict is uncertain. One estimate made in late 2006 put the total at more than 650,000 between the U.S.-led invasion and October 2006, but many other reported estimates put the figures for the same period at about 40,000 to 50,000.

Following the collapse of the Baʿthist regime, Iraq's major cities erupted in a wave of looting that was directed mostly at government offices and other public institutions, and there were severe outbreaks of violence—both common criminal violence and acts of reprisal against the former ruling clique. Restoring law and order was one of the most arduous tasks for the occupying forces, one that was exacerbated by continued attacks against occupying troops that soon developed into full-scale guerrilla warfare; increasingly, the conflict came to be identified as a civil war, although the Bush administration generally avoided using that term and instead preferred the label “sectarian violence.” Coalition casualties had been light in the initial 2003 combat, with about 150 deaths by May 1. However, deaths of U.S. troops soared thereafter, reaching some 1,000 by the time of the U.S. presidential election in November 2004 and surpassing 3,000 in early 2007; in addition, several hundred soldiers from other coalition countries have been killed. The number of Iraqis who died during the conflict is uncertain. One estimate made in late 2006 put the total at more than 650,000 between the U.S.-led invasion and October 2006, but many other reported estimates put the figures for the same period at about 40,000 to 50,000.After 35 years of Baʿthist rule that included three major wars and a dozen years of economic sanctions, the economy was in shambles and only slowly began to recover. Moreover, the country remained saddled with a ponderous debt that vastly exceeded its annual gross domestic product, and oil production—the country's single greatest source of revenue—was badly hobbled. The continuing guerrilla assaults on occupying forces and leaders of the new Iraqi government in the years after the war only compounded the difficulty of rebuilding Iraq.

In the Shīʿite regions of southern Iraq, many of the local religious leaders (ayatollahs) who had fled Ṣaddām's regime returned to the country, and Shīʿites from throughout the world were able to resume the pilgrimage to the holy cities of Al-Najaf and Karbalāʾ that had been banned under Ṣaddām. Throughout the country Iraqis began the painful task of seeking loved ones who had fallen victim to the former regime; mass graves, the result of numerous government pogroms over the years, yielded thousands of victims. The sectarian violence that engulfed the country caused enormous chaos, with brutal killings by rival Shīʿite and Sunni militias. One such Shīʿite militia group, the Mahdi Army, formed by cleric Muqtada al-Sadr (Ṣadr, Muqtadā al-) in the summer of 2003, was particularly deadly in its battle against Sunnis and U.S. and Iraqi forces and was considered a major destabilizing force in the country.

A controversial war

Unlike the common consent reached in the Persian Gulf War, no broad coalition was assembled to remove Ṣaddām and his Baʿth Party from power. Although some European leaders voiced their conditional support for the war and none regretted the end of the violent Baʿthist regime, public opinion in Europe and the Middle East was overwhelmingly against the war. Many in the Middle East saw it as a new brand of anti-Arab and anti-Islamic imperialism, and most Arab leaders decried the occupation of a fellow Arab country by foreign troops. Reaction to the war was mixed in the United States. Though several antiwar protests occurred in American cities in the lead-up to the invasion, many opinion polls showed considerable support for military action against Iraq before and during the war. Surprisingly, American opinions on the war sometimes crossed traditional party lines and doctrinal affiliation, with many to the right of the avowedly conservative Bush seeing the war as an act of reckless internationalism and some to the political left—appalled by the Baʿthist regime's brutal human rights violations and its consistent aggression—giving grudging support to military action.

As violence continued and casualties mounted, however, more Americans (including some who had initially supported the war) began to criticize the Bush administration for what they perceived to be the mishandling of the occupation of Iraq. The appearance in the news of photographs of U.S. soldiers abusing Iraqis at Abu Ghraib prison west of Baghdad—a facility notorious for brutality under the Baʿth regime—further damaged world opinion of the United States. In addition, a U.S. bipartisan commission formed to investigate the September 11 attacks reported in July 2004 that there was no evidence of a “collaborative operational relationship” between the Baʿthist government and al-Qaeda (Qaeda, al-)—a direct contradiction to one of the U.S. government's main justifications for the war.

Bush's prewar claims, the failure of U.S. intelligence services to correctly gauge Iraq's weapon-making capacity, and the failure to find any weapons of mass destruction—the Bush administration's primary rationale for going to war—became major political debating points. The war was a central issue in the 2004 U.S. presidential election, which Bush only narrowly won. Opposition to the war continued to increase over the next several years; soon only a dwindling minority of Americans believed that the initial decision to go to war in 2003 was the right one, and an even smaller number still supported the administration's handling of the situation in Iraq.

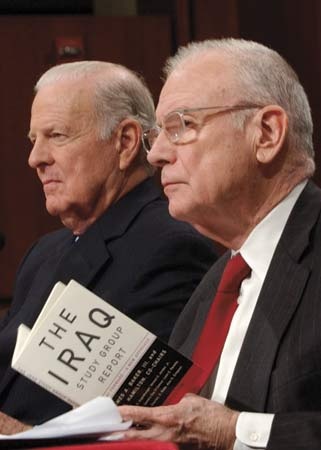

Bush's prewar claims, the failure of U.S. intelligence services to correctly gauge Iraq's weapon-making capacity, and the failure to find any weapons of mass destruction—the Bush administration's primary rationale for going to war—became major political debating points. The war was a central issue in the 2004 U.S. presidential election, which Bush only narrowly won. Opposition to the war continued to increase over the next several years; soon only a dwindling minority of Americans believed that the initial decision to go to war in 2003 was the right one, and an even smaller number still supported the administration's handling of the situation in Iraq. In late 2006 the Iraq Study Group, an independent bipartisan panel cochaired by former U.S. secretary of state James A. Baker III (Baker, James Addison, III) and former U.S. congressman Lee Hamilton, issued a report that found the situation in Iraq to be “grave and deteriorating.” The report advocated regionwide diplomatic efforts to resolve the conflict and called for the U.S. military role to evolve into one that provided diminishing support for an Iraqi government that the report challenged to assume more responsibility for the country's security. In 2007, seeking to stabilize Iraq, especially Baghdad, Bush announced a controversial plan to increase the number of U.S. troops there.

In late 2006 the Iraq Study Group, an independent bipartisan panel cochaired by former U.S. secretary of state James A. Baker III (Baker, James Addison, III) and former U.S. congressman Lee Hamilton, issued a report that found the situation in Iraq to be “grave and deteriorating.” The report advocated regionwide diplomatic efforts to resolve the conflict and called for the U.S. military role to evolve into one that provided diminishing support for an Iraqi government that the report challenged to assume more responsibility for the country's security. In 2007, seeking to stabilize Iraq, especially Baghdad, Bush announced a controversial plan to increase the number of U.S. troops there.- Moruya

- Morvan

- Morvi

- Morwell

- Morys, Huw

- Moréas, Jean

- Morón

- Morón de la Frontera

- Mosaddeq, Mohammad

- mosaic

- mosaic evolution

- mosaic glass

- mosaic rhyme

- Mosander, Carl Gustaf

- Mosan school

- mosasaur

- Mosby, John Singleton

- Mosca, Gaetano

- Moscheles, Ignaz

- Moscherosch, Johann Michael

- Moschopoulos, Manuel

- Moschops

- Moschus

- Moschus, John

- Mosconi, Willie