Korea, South

Introduction

officially Republic of Korea, Korean Taehan Min'guk

Korea, South, flag ofcountry in East Asia. It occupies the southern portion of the Korean peninsula. The country is bordered by the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea (Korea, North)) to the north, the East Sea (Sea of Japan (Japan, Sea of)) to the east, the East China Sea to the south, and the Yellow Sea to the west; to the southeast it is separated from the Japanese island of Tsushima by the Korea Strait. South Korea faces North Korea across a demilitarized zone that runs for about 150 miles (240 km) roughly from the mouth of the Han River on the west coast of the Korean peninsula to a little south of the North Korean town of Kosŏng on the east coast. South Korea makes up about 45 percent of the peninsula. The capital is Seoul (Sŏul).

The land (Korea, South)

Relief

Geologically, South Korea consists in large part of Precambrian rocks (i.e., more than 543 million years old) such as granite and gneiss. The country is largely mountainous, with small valleys and narrow coastal plains. The T'aebaek Mountains run in roughly a north-south direction along the eastern coastline and northward into North Korea, forming the country's drainage divide. From them several mountain ranges branch off with a northeast-southwest orientation. The most important of these are the Sobaek Mountains, which undulate in a long S-shape across the peninsula. None of South Korea's mountains are very high: the T'aebaek Mountains reach an elevation of 5,604 feet (1,708 metres) at Mount Sŏrak, and the Sobaek Mountains reach 6,283 feet (1,915 metres) at Mount Chiri. The highest peak in South Korea, the extinct volcano Mount Halla on Cheju Island, is 6,398 feet (1,950 metres) above sea level.

Geologically, South Korea consists in large part of Precambrian rocks (i.e., more than 543 million years old) such as granite and gneiss. The country is largely mountainous, with small valleys and narrow coastal plains. The T'aebaek Mountains run in roughly a north-south direction along the eastern coastline and northward into North Korea, forming the country's drainage divide. From them several mountain ranges branch off with a northeast-southwest orientation. The most important of these are the Sobaek Mountains, which undulate in a long S-shape across the peninsula. None of South Korea's mountains are very high: the T'aebaek Mountains reach an elevation of 5,604 feet (1,708 metres) at Mount Sŏrak, and the Sobaek Mountains reach 6,283 feet (1,915 metres) at Mount Chiri. The highest peak in South Korea, the extinct volcano Mount Halla on Cheju Island, is 6,398 feet (1,950 metres) above sea level.South Korea has two volcanic islands—Cheju, off the peninsula's southern tip, and Ullŭng (Ullŭng Island), about 85 miles (140 km) east of the mainland in the East Sea—and a small-scale lava plateau in Kangwŏn province. There are fairly extensive lowlands along the lower parts of the country's main rivers. The eastern coastline is relatively straight, whereas the western and southern have extremely complicated ria (i.e., creek-indented) coastlines with many islands. The shallow Yellow Sea and the complex Korean coastline produce one of the highest tidal ranges in the world—about 30 feet (9 metres) maximum at Inch'ŏn, the entry port for Seoul.

Drainage and soils

South Korea's three principal rivers, the Han, Kum, and Naktong, all have their sources in the T'aebaek Mountains, and they flow between the ranges before entering their lowland plains. Nearly all the country's rivers flow westward or southward into either the Yellow Sea or the East China Sea; only a few short, swift rivers drain eastward from the T'aebaek Mountains. The Naktong River, South Korea's longest, runs southward for 325 miles (523 km) to the Korea Strait. Streamflow is highly variable, being greatest during the wet summer months and considerably less in the relatively dry winter.

Most of South Korea's soils derive from granite and gneiss. Sandy and brown-coloured soils are common, and they are generally well-leached and have little humus content. Podzolic soils (ash-gray forest soils), resulting from the cold of the long winter season, are found in the highlands.

Climate

The greatest influence on the climate of the Korean peninsula is its proximity to the Asian landmass. This produces the marked summer-winter temperature extremes of a continental climate while also establishing the northeast Asian monsoons (seasonal winds) that affect precipitation patterns. The annual range of temperature is greater in the north and in interior regions of the peninsula than in the south and along the coast, reflecting the relative decline in continental influences in the latter areas.

South Korea's climate is characterized by a cold, relatively dry winter and a hot, humid summer. The coldest average monthly temperatures in winter drop below freezing except along the southern coast. The average January temperature at Seoul is about 23 °F (−5 °C), while the corresponding average at Pusan, on the southeast coast, is 35 °F (2 °C). By contrast, summer temperatures are relatively uniform across the country, the average monthly temperature for August (the warmest month) being about 77 °F (25 °C).

Annual precipitation ranges from about 35 to 60 inches (900 to 1,500 mm) on the mainland. Taegu, on the east coast, is the driest area, while the southern coast is the wettest; southern Cheju Island receives more than 70 inches (1,800 mm) annually. Up to three-fifths of the annual precipitation is received in June-August, during the summer monsoon, the annual distribution being more even in the extreme south. Occasionally, late-summer typhoons cause heavy showers and storms along the southern coast. Precipitation in winter falls mainly as snow, with the heaviest amounts occurring in the T'aebaek Mountains. The frost-free season ranges from 170 days in the northern highlands to more than 240 days on Cheju Island.

Plant and animal life

The long, hot, humid summer is favourable for the development of extensive and varied vegetation. Some 4,500 plant species are known. Forests once covered about two-thirds of the total land area, but, because of fuel needs during the long, cold winter and high population density, the original forest has almost disappeared. Except for evergreen broad-leaved forests in the narrow subtropical belt along the southern coast and on Cheju Island, most areas contain deciduous broad-leaved and coniferous trees. Typical evergreen broad-leaved species include the camellia and camphor tree, while deciduous forests include species of oak, maple, alder, zelkova, and birch. Species of pine are the most representative in the country; other conifers include spruces, larches, and yews. Among indigenous species is the Abeliophyllum distichum, a shrub of the olive family.

The long, hot, humid summer is favourable for the development of extensive and varied vegetation. Some 4,500 plant species are known. Forests once covered about two-thirds of the total land area, but, because of fuel needs during the long, cold winter and high population density, the original forest has almost disappeared. Except for evergreen broad-leaved forests in the narrow subtropical belt along the southern coast and on Cheju Island, most areas contain deciduous broad-leaved and coniferous trees. Typical evergreen broad-leaved species include the camellia and camphor tree, while deciduous forests include species of oak, maple, alder, zelkova, and birch. Species of pine are the most representative in the country; other conifers include spruces, larches, and yews. Among indigenous species is the Abeliophyllum distichum, a shrub of the olive family.Wild animal life is similar to that of northern and northeastern China. The most numerous larger mammals are deer. Tigers, leopards, lynx, and bears, formerly abundant, have almost disappeared, even in remote areas. Some 380 species of birds are found in the country, most of which are seasonal migrants. Many of South Korea's fish, reptile, and amphibian species are threatened by intensive cultivation and environmental pollution except in the demilitarized zone, where human activity has been highly restricted since the early 1950s.

Settlement patterns

Agglomerated villages are common in river valleys and coastal lowlands in rural areas, ranging from a few houses to several hundred. Villages are frequently located along the foothills facing toward the south, backed by hills that give protection from the severe northwestern winter winds. Small clustered fishing villages are found along the coastline. In contrast to the lowlands, settlements in mountain areas are usually scattered. The pace of urbanization in South Korea since 1960 has caused considerable depopulation of rural areas, and the traditional rural lifestyle has been slowly fading away.

Agglomerated villages are common in river valleys and coastal lowlands in rural areas, ranging from a few houses to several hundred. Villages are frequently located along the foothills facing toward the south, backed by hills that give protection from the severe northwestern winter winds. Small clustered fishing villages are found along the coastline. In contrast to the lowlands, settlements in mountain areas are usually scattered. The pace of urbanization in South Korea since 1960 has caused considerable depopulation of rural areas, and the traditional rural lifestyle has been slowly fading away. In contrast to rural areas, urban populations have grown enormously. Seoul, the political, economic, and cultural centre of the country, is by far the largest city; satellite cities around Seoul—notably Anyang, Sŏngnam, Suwŏn, and Puch'ŏn—also have grown rapidly, forming an extensive conurbation (Greater Seoul) to the south of the city. The other major cities with populations of at least one million are Pusan, Taegu, Inch'ŏn, Kwangju, and Taejŏn. The populations of most of the small and medium-size cities serving as rural service centres, however, generally have been stagnating.

In contrast to rural areas, urban populations have grown enormously. Seoul, the political, economic, and cultural centre of the country, is by far the largest city; satellite cities around Seoul—notably Anyang, Sŏngnam, Suwŏn, and Puch'ŏn—also have grown rapidly, forming an extensive conurbation (Greater Seoul) to the south of the city. The other major cities with populations of at least one million are Pusan, Taegu, Inch'ŏn, Kwangju, and Taejŏn. The populations of most of the small and medium-size cities serving as rural service centres, however, generally have been stagnating.The people

Ethnic and linguistic composition

The Korean people originally may have had links with the people of Central Asia, the Lake Baikal region, Mongolia, and the coastal areas of the Yellow Sea. Tools of Paleolithic type and other artifacts found in Sokch'ang, near Kongju, are quite similar to those of the Lake Baikal and Mongolian areas. The population of South Korea is highly homogeneous, although the number of foreigners is growing, especially in the major urban areas. In addition to American soldiers, urban Chinese, and foreign nationals in business or the diplomatic corps, tens of thousands of workers have come to South Korea from China and Southeast Asia.

All Koreans speak the Korean language, which is often classified as one of the Altaic languages, has affinities to Japanese, and contains many Chinese loanwords. The Korean script, known in South Korea as Hangul (Han'gŭl) and in North Korea as Chosŏn muntcha, is composed of phonetic symbols for the 10 vowels and 14 consonants. Korean often is written as a combination of Chinese ideograms and Hangul in South Korea, although the trend there is toward using less Chinese. A number of English words and phrases have crept into the language as a result of the American presence in the country since 1950.

Religion

Freedom of religion is constitutionally guaranteed in South Korea, and there is no national religion. There also is little uniformity of religious belief, a situation that often is confusing to outside observers. Thus, an individual may adhere to Buddhism while also following Confucian or Taoist tenets.

Buddhism, which was first introduced in the 4th century AD and was the official religion of the Koryŏ dynasty (918–1392), has the largest following. Christianity is relatively new in Korea, Roman Catholic missionaries having reached the peninsula only in the late 18th century, and their Protestant counterparts a century later. Christians now are the second largest religious group, with Protestants far outnumbering Catholics. Christianity has had a profound effect on the modernization of Korean society. Confucianism was the basis of national ethics during the Chosŏn (Yi) dynasty (1392–1910); though the number of its official adherents is now small, most Korean families still follow its principles, including ancestor worship. Among the so-called new religions are Wŏnbulgyo (Wŏn Buddhism), Taejongyo, and Ch'ŏndogyo. Ch'ŏndogyo (“Teaching of the Heavenly Way”), originally known as Tonghak (“Eastern Learning”), is a blend of Buddhism, Confucianism, Christianity, and even Taoism; it spread widely in the latter part of the 19th century. shamanism—the religious belief in gods, demons, and ancestral spirits responsive to a priest, or shaman—and traditional geomancy (p'ungsu) persist, though their practices usually are limited to certain occasions, such as funerals.

Demographic trends

South Korea's population more than doubled in the period 1950–90. From 1960, however, birth and mortality rates decreased rapidly. The decrease in the birth rate was caused chiefly by a national campaign for family planning conducted since 1965. It also reflected an overall increase in living standards, considerable growth in the number of educated people, and the shift from a rural and agrarian to an urban and industrial society.

The rapid increase in the urban population and the resultant depopulation of vast rural areas are South Korea's main demographic issues. Three-fourths of the population is classed as urban, with roughly half living in the country's six largest cities. Thus, although the country's rate of population growth is low, its overall population density is high—some two and a half times that of North Korea—with huge concentrations of people in the major cities. The cities are populated by young people, while the median age in rural areas becomes progressively higher.

Large numbers of Koreans emigrated before World War II: those from northern Korea to Manchuria, and those from southern Korea to Japan. It is estimated that in 1945 some two million Koreans lived in Manchuria and Siberia and about the same number in Japan. About half of the Koreans in Japan returned to South Korea just after 1945. The most important migration, however, was the north-to-south movement of people after World War II, especially the movement that occurred during and after the Korean War. About two million people migrated to South Korea from the North during that period, settling largely in the major cities. In addition to creating large resident populations in China and Japan, Koreans have emigrated to many other countries, notably the United States and Canada.

The economy

The South Korean economy has grown remarkably since the early 1960s. In that time, South Korea transformed itself from a poor, agrarian society to one of the world's most highly industrialized nations. This growth was driven primarily by the development of export-oriented industries, fostered by strong government support. Government and business leaders together fashioned a strategy of targeting specific industries for development, and beginning in 1962 this strategy was implemented in a series of economic development plans. The first targeted industries were textiles and light manufacturing, followed in the 1970s by such heavy industries as iron and steel and chemicals. Still later, the focus shifted to such enterprises as automobiles and electronics.

The government exercised strong controls on industrial development, giving most support to the large-scale projects of the emerging giant corporate conglomerates called chaebŏl. As a result, small and medium-size industries that were privately managed became increasingly difficult to finance, and many of these became, in essence, dependent subcontractors of the chaebŏl. In addition, preferential reinvestment in export industries discouraged the production of consumer goods and held down consumer spending. By 1980, however, these policies began to be reversed, especially credit policies, as the government gradually removed itself from direct involvement in industry.

Labour unions were able to win significant increases in wages during the 1980s, which improved the lot of workers and produced a corresponding growth in domestic consumption. Higher labour costs, however, contributed to a decline in international competitiveness in such labour-intensive activities as textile manufacture.

Mining and power

Mineral resources in South Korea are meagre. The most important reserves are of anthracite coal, iron ore, graphite, gold, silver, tungsten, lead, and zinc, which together constitute some two-thirds of the total value of mineral resources. Deposits of graphite and tungsten are among the largest in the world. Most mining activity centres around the extraction of coal and iron ore. All of the country's crude petroleum requirements and most of its metallic mineral needs (including iron ore) are met by imports.

Thermal electric power accounts for more than half of the power generated. Since the first oil refinery started to produce petroleum products in 1964, power stations have changed over gradually from coal to oil. Hydroelectricity constitutes only a small proportion of overall electric-power production; most stations are located along the Han River, not far from Seoul. Nuclear power generation, however, has become increasingly important.

Agriculture

Less than one-fourth of the republic's area is cultivated. Along with the decrease in farm population, the proportion of national income derived from agriculture has decreased to a fraction of what it was in the early 1950s. Improvements in farm productivity have been hampered because fields typically are divided into tiny plots that are cultivated largely by manual labour and animal power. In addition, the decrease and aging of the rural population has caused a serious farm-labour shortage. Rice is the most important crop, constituting about two-fifths of all farm production in value. Barley, wheat, soybeans, potatoes, millet, and a wide variety of vegetables also are important. Double-cropping of rice and barley is common in the southern provinces.

Forestry and fishing

From the 1970s successful reforestation efforts were mounted in areas previously denuded. Domestic timber production, however, supplies only a negligible fraction of demand. Logging, mainly of coniferous trees, is limited to the mountain areas of Kangwŏn and North Kyŏngsang provinces. A large plywood and veneer industry has been developed, based on imported wood.

Fishing has long been important for supplying protein-rich foods and has emerged as a significant export source. South Korea has become one of the world's major deep-sea fishing nations. Coastal fisheries and inland aquaculture also were developed.

Industry

Textiles (textile) and other labour-intensive industries have declined from their former preeminence in the national economy, although they remain important, especially in export trade. Heavy industries, including chemicals, metals, machinery, and petroleum refining, are highly developed. Industries that are even more capital- and technology-intensive grew to importance after 1980—notably shipbuilding, motor vehicles, and electronic equipment. Also from the 1980s, increasing emphasis was given to such high-technology industries as bioengineering and aerospace, and the service industry grew markedly. Much of the country's manufacturing is centred on Seoul, while heavy industry is largely based in the southeast; notable among the latter enterprises is the large integrated-steel facility at P'ohang.

Finance and trade

The government-owned Bank of Korea, headquartered in Seoul, is the country's central bank, issuing currency and overseeing all banking activity. All banks were nationalized in the early 1960s, but by the early 1990s these largely had been returned to private ownership. Foreign branch banking has been allowed in South Korea since the 1960s, and in 1992 foreigners began trading on the Korea Stock Exchange in Seoul.

South Korea borrowed heavily on international financial markets to supply capital for its industrial expansion, but the success of its exports allowed it to repay much of its debt. The country generally runs a modest annual trade deficit. The major imports are machinery, mineral fuels, manufactured goods, and such crude materials as textile fibres and metal ores and scrap. Principal exports include machinery, textiles, transport equipment, and clothing and footwear. South Korea's principal trading partners are the United States, Japan, members of the European Union, and Southeast Asian countries.

Transportation

South Korea's transportation system was expanded and improved considerably after 1960, especially with the creation of a modern highway network and the establishment of nationwide air service. Road construction, however, did not keep up with the tremendous increase in the number of motor vehicles in the country, especially in urban areas. Road transport now accounts for the bulk of passenger travel and most movement of freight. The country's first multilane highway (from Seoul to Inch'ŏn) was opened in 1968, and the express highway network subsequently was expanded to link most major cities. The bus transportation network is well developed.

The South Korean railways are largely government-owned. Until 1960 rail travel was the major means of inland transportation for both freight and passengers but since has been superseded by road transport, and, more recently, by the rise in air travel. Railways are almost all of standard gauge, the Seoul-Pusan line through Taejŏn and the Seoul-Inch'ŏn line are double-tracked, and many lines are electrified. Seoul and Pusan have heavily used subway systems.

Internal air transportation began in the early 1960s. Most major cities now have scheduled air services. Kimp'o International Airport, at Seoul, serves as the country's main port of entry, and Pusan and Cheju also have international airports. Port facilities have been expanded considerably with the tremendous growth in trade. Major ports include Pusan, Inch'ŏn, Ulsan, and Cheju.

Administration and social conditions

Government

The government instituted after a constitutional referendum in 1987 is known as the Sixth Republic. The government structure is patterned mainly on the presidential system of the United States and is based on separation of powers among the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary. The government system, highly centralized during most of South Korea's existence, is less so under the Sixth Republic. The president, since 1987 chosen by direct popular election for a single five-year term, is the chief of state, head of the executive branch, and commander of the armed forces. The State Council, the highest executive body, is composed of the president, the prime minister, the heads of executive ministries, and ministers without portfolio. The prime minister is appointed by the president and approved by the elected National Assembly.

Legislative authority rests with the unicameral National Assembly (Kuk Hoe). The powers of the National Assembly, which was reinstated in 1980 after a period of curtailment, were strengthened in 1987. Its 299 members are chosen, as previously, by a combination of direct and indirect election to four-year terms.

South Korea is divided administratively into the nine provinces (do or to) Cheju, North Chŏlla, South Chŏlla, North Ch'ungch'ŏng, South Ch'ungch'ŏng, Kangwŏn, Kyŏnggi, North Kyŏngsang, and South Kyŏngsang; the special city (t'ŭkpyŏlsi) of Seoul; (Seoul) and the five megalopolises (kwangyŏksi) Pusan, Taegu, Inch'ŏn, Kwangju, and Taejŏn. Each has a popularly elected legislative council. Provinces are further divided into counties (gun) and cities (si), and the large cities into wards (ku) and precincts (tong). Provincial governors and the mayors of province-level cities are popularly elected.

South Korea had a two-party system until 1972, when the power of the pro-government party increased substantially and the activity of the opposition was restricted. During the 1980s restrictions on political parties were ended. The opposition was allowed to resume political participation, but it also tended to fragment; thus, the political system became more multiparty in character. The Democratic Justice Party (DJP; until 1981 called the Democratic Republican Party), the ruling party since its founding in 1963, was renamed the Democratic Liberal Party in 1990, following the merger of the DJP with two opposition parties. The Democratic Party and the Unification National Party have become the major opposition parties.

Justice

The judicial branch consists of the Supreme Court, three appellate courts, 12 district courts, and a family court. The Supreme Court is empowered to interpret the constitution and all other state laws and to review the legality of government regulations and activities. The chief justice is appointed by the president with the consent of the National Assembly, upon recommendation of the Judge Recommendation Council.

Armed forces and security

South Korea maintains a large, well-equipped armed-forces establishment—consisting of army, navy, and air force branches—although it is still considerably smaller than that of North Korea. The army is by far the largest component, and there is a sizable reserve force. Military service is compulsory for all males. South Korea's main military objective is to deter an attack by the North. To that end it has a Mutual Defense Treaty (1953) with the United States, and a large contingent of U.S. troops is stationed in the country.

Civilian intelligence gathering and other nonmilitary matters of national security are the responsibility of the Agency for National Security Planning (until 1980 called the Korean Central Intelligence Agency). Military intelligence is handled by the Defense Security Command. The Korean National Police combine standard police duties with responsibility for counteracting communist infiltration and controlling civil disorders.

Education

Six years of primary-school education is compulsory, and virtually all children of school age are enrolled. Most primary-school graduates go on to three years of middle school, and nearly all middle-school graduates continue on in high school or technical school. About one-third of the high-school graduates go to higher educational institutions. Graduation from a college or university grew considerably in importance in South Korea after World War II, and the number of college-level institutions increased enormously. Nearly all the most prestigious schools are located in Seoul and include the state-run Seoul National University and the private Ehwa Woman's University and Yonsei University. Admission to a school is granted through competitive entrance examinations. High-school students must endure grueling preparation work for these examinations.

Health and welfare

The availability of medical services increased enormously after the Korean War, but medical facilities and the number of personnel remain inadequate, especially in rural areas. Most people now have some sort of medical insurance coverage. Public health and sanitation have greatly improved, thus reducing epidemics. The average life-expectancy rate rose dramatically from the 1950s, while the death rate more than halved.

Government welfare activities are relatively new and limited in range. The programs include care of disabled war veterans, a variety of homes (for the aged, homeless, disabled war widows, and orphans), vocational training of women, and care of juvenile delinquents. Following on the devastation of the Korean War, United Nations agencies, civilian and military agencies of the United States, and private volunteer agencies played a significant role in the steadily improving living conditions in South Korea. Also significant was the dramatic increase in household income, especially among industrial workers. Despite these overall improvements, there is little sign of a narrowing of the disparity in the quality of life between rural and urban dwellers.

Housing

Rapid expansion of urban areas, especially the expansion of Seoul and Pusan, has resulted in considerable changes in the urban landscape. Before 1960 there were few multistory buildings; even in Seoul, most structures were lower than 10 stories. High-rise buildings, especially apartment blocks, are now common in the city. Because of this rapid growth, city services, such as water, transportation, and sewage systems, generally have not been able to keep up with this growth. Despite the rapid pace of urban housing construction, the shortage of housing in metropolitan areas has remained a problem, although it has been partially solved by central and local government-housing programs.

Cultural life

Shamanism, Buddhism, and Confucianism constitute the background of modern Korean culture. Since World War II, and especially after the Korean War, the modern trends have rapidly progressed. Traditional thought, however, still plays an important role under the surface. Korea belongs historically to the Chinese cultural realm. After the Three Kingdoms period in particular, Korean culture was strongly influenced by the Chinese, although this influence was given a distinctive Korean stamp. The National Museum of Korea maintains artifacts of Korean culture, including many national treasures, chiefly in the central museum in Seoul; there are branch museums in eight other cities. Archaeological sites include the ancient burial mounds at Kyŏngju, capital of the Silla (Shilla) kingdom, and Kongju and Puyŏ, two of the capitals of Paekche.

Shamanism, Buddhism, and Confucianism constitute the background of modern Korean culture. Since World War II, and especially after the Korean War, the modern trends have rapidly progressed. Traditional thought, however, still plays an important role under the surface. Korea belongs historically to the Chinese cultural realm. After the Three Kingdoms period in particular, Korean culture was strongly influenced by the Chinese, although this influence was given a distinctive Korean stamp. The National Museum of Korea maintains artifacts of Korean culture, including many national treasures, chiefly in the central museum in Seoul; there are branch museums in eight other cities. Archaeological sites include the ancient burial mounds at Kyŏngju, capital of the Silla (Shilla) kingdom, and Kongju and Puyŏ, two of the capitals of Paekche.Architecture

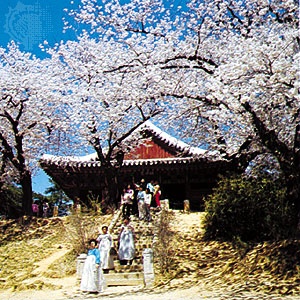

Korean architecture shows Chinese influence, but it is adapted to local conditions, utilizing wood and granite, the most abundant building materials. Beautiful examples are found in old palaces, Buddhist temples, stone tombs, and Buddhist pagodas. Western-style architecture became common from the 1970s, fundamentally changing the urban landscape.

Painting and ceramics

One of the earliest examples of Korean painting is found in the mural paintings in the royal tombs of Koguryŏ. The best-known mural paintings are those in the Ssangyong Tomb at Yonggang, located in North Korea. Ceramic arts became highly developed, flourishing during the Koryŏ period and diffusing to Japan, and every province continues to produce its distinctive ceramic wares. The largest collection of contemporary art is in the National Museum of Modern Art at Kwach'ŏn, near Seoul.

Dance and music

Folk dances survive, and folk music, accompanied by native musical instruments, is performed occasionally at ceremonies and festive occasions. The government has made an effort to preserve the traditional arts. The National Classical Music Institute (formerly the Prince Yi Conservatory), for example, plays an important role in the preservation of folk music. It has had its own training centre for national music since 1954. The Korean National Symphony Orchestra and the Seoul Symphony Orchestra are two of the best-known organizations performing Western music.

Recreation

South Koreans are avid sports and outdoors enthusiasts. The martial art tae kwon do and the traditional wrestling style called ssirŭm are widely practiced national sports. There are well-supported professional baseball and football (soccer) leagues. The 1988 Summer Olympic Games at Seoul not only were an enormous boost for national pride but were the catalyst for the construction of many new sports and cultural facilities and for the enhancement of Korean cultural identity. The country's system of national parks attracts large numbers of hikers, campers, and skiers.

The press and broadcasting

Constitutionally guaranteed press freedoms, often violated before 1987, are now generally observed. There are a number of nationally distributed daily newspapers (including economic, sports, and English-language papers) and many regional and local dailies. The Yŏnhap News Agency is the largest such organization. In addition to the publicly owned Korean Broadcasting System, a growing number of private radio and television stations have been established.

History

The following is a treatment of South Korea since the Korean War. For a discussion of the earlier history of the peninsula, see Korea, history of (Korea).

South Korea to 1961

The First Republic

The First Republic, established in August 1948, adopted a presidential system, and Syngman Rhee (Rhee, Syngman) was subsequently elected its first president. It also adopted a National Security Law, which effectively prohibited groups that opposed the state or expressions of support for North Korea. Rhee was reelected in August 1952 while the country was at war. Even before the outbreak of the Korean War, there had been a serious conflict between Rhee and the opposition-dominated National Assembly that had elected him in 1948. The dispute involved a constitutional amendment bill that the opposition introduced in an attempt to oust Rhee by replacing the presidential system with a parliamentary cabinet system. The bill was defeated, but the dispute continued at Pusan, the wartime provisional capital, where the National Assembly was reconvened.

When the opposition introduced another amendment bill in favour of a parliamentary cabinet system, Rhee in 1952 countered by pushing through a bill that provided for the popular election of the president. Later, in 1954, Rhee succeeded in forcing the National Assembly, then dominated by the ruling party, to pass an amendment that exempted him from what was then a two-term limit on the presidency. Under the revised constitution, Rhee ran successfully for his third term of office in May 1956. His election for the fourth time, in March 1960, was preceded by a period of tension and violence. Amid massive student demonstrations, which culminated in a major event on April 19 with many casualties, Rhee resigned under pressure and fled to exile in Hawaii, where he died in 1965 at age 90.

The Second Republic

The Second Republic, which adopted a parliamentary cabinet system, lasted only nine months before it was overthrown by a military coup in May 1961. A figurehead president was elected by both houses of the legislature, and power was shifted to the office of Prime Minister Chang Myŏn, who was elected by the lower house by a narrow margin of 10 votes.

The Chang government made some strenuous efforts to initiate reforms. In a society laden with social and economic ills accumulated over a long period of time, however, it failed to cope with the unstable situation created by a violent political change. Rampant political factionalism only made the situation worse. With the ultimate source of authority now vested in the office of the prime minister, all factions, conservative and moderate, engaged in constant maneuvering to win over a group of independents in order to form a majority in the legislature. Before Chang had time to launch a full program of economic reform, the leadership of the ruling Democratic Party was crippled by factional strife within its ranks.

Military rule

The 1961 coup

On May 16, 1961, the military seized power through a carefully engineered coup d'état, ushering in a new phase of postliberation Korean politics. The military junta, led by General Park Chung Hee, took over the government machinery, dissolved the National Assembly, and imposed a strict ban on political activity. The country was placed under martial law, and the Supreme Council for National Reconstruction (SCNR), headed by Park, took the reins of government and began instituting a series of reforms.

In November 1962 the SCNR made public a constitutional amendment bill that provided for a strong president and a weak, single-chamber National Assembly. The bill was approved by a national referendum one month later. A series of events unfolded in the first half of 1963. In February Park announced that he would not take part in the civilian government to be formed later in the year if civilian political leaders chose to uphold a nine-point “political stabilization proposal.” However, as a result of bitter turbulence within the ruling junta and a chaotic situation created by the proliferation of minor political parties, Park soon changed his mind and proposed that military rule be extended for four years. The proposal met vigorous opposition from civilian political leaders, but some 160 military commanders, most of them generals, supported the extension. In April Park, under considerable domestic and international pressure (particularly from the United States), announced a plan for holding elections toward the end of the year. Park was named presidential candidate of the newly formed Democratic Republican Party (DRP) in late May.

The Third Republic

The election for president of the Third Republic took place on October 15, 1963. Park narrowly defeated the opposition candidate, Yun Po Sun (Yun Po Sŏn), former president (1960–62) of the Second Republic, who had remained in office as a figurehead at the request of the junta to provide constitutional continuity for the military regime. When political activity was permitted to resume, Yun led the mustering opposition groups and became the presidential candidate of the Civil Rule Party. In May 1967 Park was elected to his second term of office, and the DRP won a large majority in the National Assembly. Members of the opposition New Democratic Party (NDP) and its candidate, the twice-defeated Yun, claimed fraud and refused for some time to take their seats in the National Assembly.

During his second term, President Park faced the constitutional provision that limited the president to two consecutive four-year terms. Amid considerable political turmoil created by the demonstrations of opposition politicians and students, the DRP members of the legislature passed a constitutional amendment that would make a president eligible for three consecutive four-year terms. The amendment was approved by a national referendum in October 1969. In the presidential elections held in April 1971, Park defeated Kim Dae Jung of the NDP; however, the NDP made substantial gains in elections for the eighth National Assembly, securing 89 seats as against 113 seats won by the ruling DRP.

The Yushin order (Fourth Republic)

In December 1971, shortly after his inauguration to a third presidential term, Park declared a state of national emergency, and 10 months later (October 1972) he suspended the constitution and dissolved the legislature. A new constitution, which would permit the reelection of the president for an unlimited number of six-year terms, was promulgated in December, launching the Fourth Republic.

The institutional framework of the Yushin (“Revitalization Reform”) order departed radically from the Third Republic. The National Conference for Unification (NCU) was created “to pursue peaceful unification of the fatherland.” The conference was to be a body of not fewer than 2,000 nor more than 5,000 members who were directly elected by the voters for a six-year term. The president was chairman of the conference. Until 1987 the NCU was charged with the power to elect the president, and under this arrangement, Park was elected without opposition in 1972 and was reelected in 1978.

Political unrest increased following the August 1973 kidnapping from Tokyo to Seoul of Kim Dae Jung—who had been conducting an antigovernment campaign in the United States and Japan—by agents of the Korean Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA). From August 1978 the opposition movement became stronger. The expulsion from the National Assembly of the new NDP leader Kim Young Sam in early October 1979 escalated what had already been growing political tensions between the government and opposition leaders during the year into a major national crisis. Antigovernment riots broke out in Pusan and Masan and were suppressed by government troops. The crisis culminated on October 26, when President Park was assassinated by Kim Jae Kyu, his longtime friend and director of the KCIA. Prime Minister Choi Kyu Hah became acting president under the Yushin constitution and was formally elected president in December by the NCU.

In the meantime, the country was placed under stern military rule by General Chun Doo Hwan. An armed uprising of students and other citizens in Kwangju in May 1980, calling for the full restoration of democracy, was ruthlessly suppressed by the military junta, with hundreds of civilian deaths. That month the military did away with all trappings of civilian government, extended martial law, again banned all political activity, and closed universities and colleges.

Restoration of civilian government

The Fifth Republic

In August 1980 Chun Doo Hwan was elected president by the NCU. A new constitution, under which the president was limited to one seven-year term, was approved in October, ushering in the Fifth Republic. Martial law was lifted in January 1981, and in February Chun was elected president under the new constitution. As parties were again allowed to operate, a new ruling party, the Democratic Justice Party (DJP), was formed by former members of the DRP and NDP. Chun's administration, however, had to endure a series of scandals and incidents—most notably the bombing by North Koreans in Rangoon, Burma (now Yangon, Myanmar), in October 1983 that killed several members of the South Korean government.

By 1987 popular dissatisfaction with the government had become widespread. To address this crisis, Roh Tae Woo (from 1985 chairman of the DJP) announced a program of constitutional reforms that would restore the democratic institutions and basic civil rights that had been usurped under military rule. Chun, compelled to accept this program, oversaw the drafting of a revised constitution, which was approved by a national referendum in October. Among its principal provisions were a reduction in the presidential term from seven to five years and the direct popular election of the president. Roh, a former army general, was elected president in December and took office in February 1988. With his inauguration, a peaceful transfer of power was effected for the first time in South Korean history, and the tortuous history of the Fifth Republic came to an end.

The Sixth Republic

In the much-improved political climate of the Sixth Republic, South Korea hosted the highly successful Summer Olympic Games in Seoul later that year. Roh proceeded to bring about a merger (1990) of the DJP with the Reunification Democratic Party of Kim Young Sam and the New Democratic Republican Party of Kim Jong Pil, who for a time had been prime minister during the Fourth Republic. The resultant Democratic Liberal Party (DLP) commanded a large majority in the National Assembly.

While it was reestablishing democracy in the domestic political arena, the Roh government initiated the so-called “northern diplomacy” policy toward the Soviet Union and its allies. These efforts brought about the establishment of diplomatic ties with Hungary, Poland, and Yugoslavia in 1989 and with the Soviet Union in 1990. Relations between South Korea and China improved as well, and in 1992 the two countries established full diplomatic ties. That December Kim Young Sam was elected president on the DLP ticket, and he succeeded Roh in February 1993.

Kim, the first civilian president in more than 30 years, sought to extricate the military from power and to reassert civilian supremacy over the military. Shortly after taking office, he purged thousands of bureaucrats, military leaders, and businessmen, released thousands of political prisoners, and launched a major anticorruption initiative (notably banning bank accounts under false names). Kim's popularity surged, but a severe economic downturn and the continued entrenchment of corruption (Kim's own son was arrested on charges of bribery and tax evasion) diminished his standing by the end of his term. He also oversaw a historic reform of local government. Local elections, which had been suspended indefinitely in 1961, were reinstated in limited fashion in 1991 and fully restored in 1995, allowing voters to choose governors and mayors of major cities. During Kim's term his two predecessors, Chun Doo Hwan and Roh Tae Woo, were arrested. Roh had shocked the country by admitting that he had amassed a political slush fund of some $650 million, and both men were convicted of corruption for having plotted the 1979 coup that had brought Chun to power and for treason in the massacre of protestors at Kwangju in 1980; Chun was sentenced to death, Roh to 22.5 years imprisonment (commuted to life imprisonment and 17 years, respectively). In addition, nine executives of South Korea's chaebol (business conglomerates) were convicted of bribing Chun and Roh in return for government favours.

In December 1997 perennial opposition candidate Kim Dae Jung was elected president of South Korea, narrowly defeating the New Korea Party (NKP; the renamed DLP) nominee. Shortly after the election, Chun and Roh were pardoned in a gesture of goodwill, and on February 25, 1998, Kim was sworn in as president in the first peaceful transition of power to the opposition. Kim implemented a so-called “sunshine” policy with the North, which led in 2000 to a historic summit between Kim and his North Korean counterpart, Kim Jong Il, and to Kim Dae Jung's selection as the recipient of that year's Nobel Prize for Peace. Nevertheless, his administration was also plagued by corruption scandals, and his international policies met resistance from the United States. Still, in 2002 South Korea basked in the success of the World Cup association football (soccer) finals, which it cohosted with Japan and at which its national team played better than ever, and in the success of the Asian Games, which it hosted in Pusan.

In 2003 Kim was succeeded as president by Roh Moo Hyun of Kim's Millennium Democratic Party (United New Democratic Party). A lawyer, Roh was a strong supporter of democratic reforms and had established himself as a defender of leftist demonstrators. Roh faced intense opposition from the more conservative Grand National Party (the former NKP), and in 2004 he was impeached by the National Assembly. Roh temporarily withdrew from office while the Constitutional Court considered the charges. In parliamentary elections that year, his party captured a majority in the National Assembly; Roh was subsequently acquitted, and he resumed office. In the 2007 presidential election, the Grand National candidate, former Seoul mayor Lee Myung-bak, won in a landslide. Legislative elections the following year gave the Grand National Party a slim majority in the National Assembly.

Relations with the North

Tensions between South Korea and the North remained high after the Korean War, exacerbated by such incidents as the assassination attempt on Park Chung Hee by North Korean commandos in 1968, the bombing in Rangoon in 1983, and the North's destruction by time bomb of a South Korean airliner over the Thai-Burmese border in 1987. The first significant contact between the two states occurred in early 1972, when the Park (Park Chung Hee) government carried out secret negotiations with North Korea. A joint statement was issued in July that announced agreement on a formula for national reunification. The ensuing dialogue between North and South, however, was short-lived.

In the early 1990s there were again signs of rapprochement between the two Koreas. North-South relations appeared to reach a milestone when a pact of reconciliation and nonaggression was signed in December 1991. Earlier that year, North Korea had retreated from its insistence on a single, shared Korean membership in the United Nations, and the two states were separately admitted to the UN on September 17. North Korea's nuclear weapons capabilities emerged as a source of anxiety for the South shortly thereafter. With the death of the North Korean leader Kim Il-sung in July 1994, hope was rekindled for further reconciliation and for a peaceful reunification of the peninsula, and in October the nuclear issue appeared settled when the North agreed to close an experimental nuclear reactor in exchange for the United States arranging for the financing and construction of two reactors capable of producing electrical power.

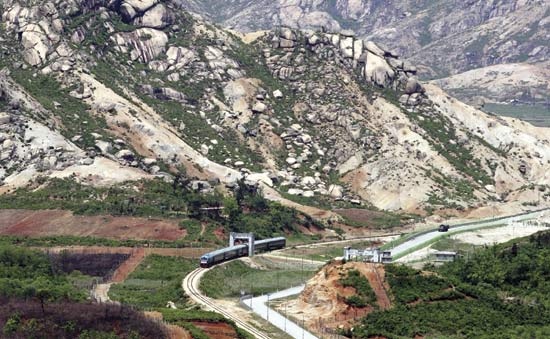

In 2000 many Koreans believed that the time might be near when the peninsula would be reunified. Kim Dae Jung's sunshine policy led to a summit with the North Korean leader, and some families were permitted to travel across the border for reunions. In addition, since 2000, North and South Korean athletes have marched under a single flag showing an image of the peninsula during the opening and closing ceremonies of the Olympic Games and Asian Games. Nevertheless, relations subsequently soured as North Korea admitted it had continued developing nuclear weapons; in 2005 the North admitted that it possessed such weapons, and in October 2006 it tested its first nuclear device. Dialogue between the two sides continued, however, resulting in two significant events in 2007: in May trains from both the North and the South crossed the demilitarized zone to the other side, the first such travel since the Korean War; and in October Roh Moo Hyun met Kim Jong Il in P'yŏngyang for a second summit.

In 2000 many Koreans believed that the time might be near when the peninsula would be reunified. Kim Dae Jung's sunshine policy led to a summit with the North Korean leader, and some families were permitted to travel across the border for reunions. In addition, since 2000, North and South Korean athletes have marched under a single flag showing an image of the peninsula during the opening and closing ceremonies of the Olympic Games and Asian Games. Nevertheless, relations subsequently soured as North Korea admitted it had continued developing nuclear weapons; in 2005 the North admitted that it possessed such weapons, and in October 2006 it tested its first nuclear device. Dialogue between the two sides continued, however, resulting in two significant events in 2007: in May trains from both the North and the South crossed the demilitarized zone to the other side, the first such travel since the Korean War; and in October Roh Moo Hyun met Kim Jong Il in P'yŏngyang for a second summit.Economic and social developments

In the 1950s South Korea had an underdeveloped, agrarian economy that depended heavily on foreign aid. The military leadership that emerged in the early 1960s and led the country for a quarter century may have been autocratic and, at times, repressive, but its pragmatic and flexible commitment to economic development resulted in what became known as the “miracle on the Han River.” During the next three decades, the South Korean economy grew at an average annual rate of nearly 9 percent, and per capita income increased more than a hundredfold. South Korea was transformed into an industrial powerhouse with a highly skilled labour force. In the late 20th century, however, economic growth slowed, and in 1997 South Korea was forced to accept a $57 billion bailout from the International Monetary Fund (IMF)—then the largest such rescue in IMF history. The country also wrestled with reforming the chaebol and liberalizing its economy. Nevertheless, its economy enjoyed a recovery in subsequent years, and the country entered the 21st century on a relatively firm economic footing.

South Korean society underwent an equally rapid transformation after the Korean War. The population more than doubled between the end of the war and the turn of the 21st century. Simultaneously, modern education developed rapidly, again with considerable government involvement but also because of the resurgence of the Korean people's traditional zeal for education after decades of repression during the Japanese occupation period. The growth of educational institutions and of commercial and industrial enterprises in and around South Korea's major cities attracted an increasing number of rural people to urban areas. Seoul, in particular, grew some 10-fold to about 10 million people between the end of World War II and the early 21st century. There was a corresponding growth in communications media, especially newspaper and magazine publishing. An ambitious program was also undertaken to expand and modernize the country's transportation infrastructure.

The most conspicuous social change in South Korea, however, was the emergence of a middle class. Land reform carried out in the early 1950s, together with the spread of modern education and the expansion of the economy, caused the disappearance of the once-privileged yangban (landholding) class, and a new elite emerged from the ranks of the former commoners. Another significant social change was the decline of the extended-family system: rural-to-urban migration broke traditional family living arrangements, as urban dwellers tended to live in apartments as nuclear families and, through family planning, to have fewer children. In addition, women strenuously campaigned for complete legal equality and won enhanced property ownership rights.

Additional Reading

General works

Shannon McCune, Korea's Heritage: A Regional & Social Geography (1956), and Korea, Land of Broken Calm (1966), provide a general description of Korea's geography, people, and culture. Donald Stone Macdonald, The Koreans: Contemporary Politics and Society, 2nd ed. (1990), covers geography, history, culture, and economics and explores the issues regarding the reunification of the peninsula.Traditional attitudes, customs, and values in Korea are outlined in Paul S. Crane, Korean Patterns, 4th ed., rev. (1978). Hagan Koo (ed.), State and Society in Contemporary Korea (1993), discusses the social movements of North and South Korea. Women's roles are studied by Yung-chung Kim (ed. and trans.), Women of Korea: A History from Ancient Times to 1945, trans. from Korean (1976); and Sandra Mattielli (ed.), Virtues in Conflict: Tradition and the Korean Woman Today (1977). Jon Carter Covell, Korea's Cultural Roots (1981), is an introduction; while Tae Hung Ha, Guide to Korean Culture (1968), surveys the varied phases of Korean culture. Comprehensive treatments of all Korean arts include Evelyn McCune, The Arts of Korea (1962); Chewŏn Kim and Lena Kim Lee (I-na Kim), Arts of Korea (1974), and The Arts of Korea, 6 vol. (1979).Works on Korean economic history include Sang Chul Suh (Chang Chul Suh), Growth and Structural Changes in the Korean Economy, 1910–1940 (1978); and Norman Jacobs, The Korean Road to Modernization and Development (1985), which begins with imperial Korea. The political climate of the peninsula is surveyed in Sung Chul Yang, The North and South Korean Political Systems (1994); Joungwon Alexander Kim (Chong-wŏn Kim), Divided Korea: The Politics of Development, 1945–1972 (1975); Young Whan Kihl, Politics and Policies in Divided Korea: Regimes in Context (1984), an informative comparative study of North and South Korean political systems after 1948; Bruce Cumings, The Two Koreas (1984), a brief study; Ralph N. Clough, Embattled Korea: The Rivalry for International Support (1987); and Eui-gak Hwang, The Korean Economies: A Comparison of North and South (1993).

Geography

Andrea Matles Savada and William Shaw (eds.), South Korea, a Country Study, 4th ed. (1992), is a good general source on social, political, economic, and national security matters. Lee Chan (Ch'an Yi) et al., Korea: Geographical Perspectives (1988); and Hermann Lautensach, Korea: A Geography Based on the Author's Travels and Literature, trans. and ed. by Katherine Dege and Eckart Dege (1988; originally published in German, 1945), are also useful. Korea Annual compiles chronologies, history, statistics, and yearly highlights, with an emphasis on South Korea. Korean Overseas Information Service, A Handbook of Korea, 8th ed. (1990), also focuses on South Korea, with a detailed discussion of and extensive bibliography on the land, people, history, culture, arts, customs, government, foreign policy, and social developments. Patricia M. Bartz, South Korea (1972), is a descriptive geography. A socioanthropological work by Vincent S.R. Brandt, A Korean Village Between Farm and Sea (1971, reissued 1990), studies a village on the Yellow Sea. Two analyses of Korean religious life are Roger L. Janelli and Dawnhee Yim Janelli, Ancestor Worship and Korean Society (1982); and Donald N. Clark, Christianity in Modern Korea (1986).Studies of South Korea's economic development include Dennis L. McNamara, The Colonial Origins of Korean Enterprise, 1910–1945 (1990); Paul W. Kuznets, Economic Growth and Structure in the Republic of Korea (1977); Edward S. Mason et al., The Economic and Social Modernization of the Republic of Korea (1980); Noel F. McGinn et al., Education and Development in Korea (1980); Alice H. Amsden, Asia's Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization (1989); Richard M. Steers, Yoo Keun Shin (Yu-gŭn Sin), and Gerardo R. Ungson, The Chaebol: Korea's New Industrial Might (1989); Byung-nak Song (Pyŏng-nak Song), The Rise of the Korean Economy (1990); Il Sakong, Korea in the World Economy (1993), by a former finance minister; Cho Soon (Soon Cho), The Dynamics of Korean Economic Development (1994); and a work edited by Sung Yeung Kwack (Sŭng-yŏng Kwack), The Korean Economy at a Crossroad: Development Prospects, Liberalization, and South-North Economic Integration (1994).Political developments in South Korea are presented in Hahn-been Lee, Korea: Time, Change, and Administration (1968), an imaginative survey of administrative behaviour under conditions of rapid social change in the country; Edward Reynolds Wright (ed.), Korean Politics in Transition (1975); Ilpyong J. Kim and Young Whan Kihl (eds.), Political Change in South Korea (1988), on more recent events; and Han Sung-joo (Sŭng-ju Han) and Robert J. Myers (eds.), Korea: The Year 2000 (1987), a sociopolitical and economic forecast.

History

Studies of South Korea's history include John Kie-chiang Oh, Korea: Democracy on Trial (1968), beginning with Syngman Rhee's administration; Sŭng-ju Han, The Failure of Democracy in South Korea (1974), a study of the causes of the collapse of Chang Myŏn's liberal democratic government in May 1961; Donald N. Clark (ed.), The Kwanju Uprising: Shadows Over the Regime in South Korea (1988); Harold C. Hinton, Korea Under New Leadership: The Fifth Republic (1983); and Frank Gibney, Korea's Quiet Revolution: From Garrison State to Democracy (1992).

- Robinson, Boardman

- Robinson, Brooks, Jr.

- Robinson, Eddie

- Robinson, Edward

- Robinson, Edward G.

- Robinson, Edwin Arlington

- Robinson, Frank

- Robinson, Harriet Jane Hanson

- Robinson, Henry Crabb

- Robinson, Henry Peach

- Robinson, Henry Wheeler

- Robinson, Jackie

- Robinson, James Harvey

- Robinson Jeffers

- Robinson, Joan

- Robinson, John

- Robinson, Joseph T

- Robinson, Lennox

- Robinson, Mary

- Robinson, Max

- Robinson, Robert

- Robinson, Rubye

- Robinson, Sir Hercules

- Robinson, Sir Robert

- Robinson, Smokey, and the Miracles