opera

music

Introduction

a drama set to music and made up of vocal (vocal music) pieces with orchestral accompaniment and with orchestral overtures and interludes. In some operas, such as those by Richard Wagner (Wagner, Richard), the music is continuous throughout an act; in others, it is broken up either by recitative (which is more like sung speech) or by dialogue. This article focuses on opera in the Western tradition. For an overview of opera in East Asia (particularly China), see East Asian arts: Dance and theatre (arts, East Asian); see also short entries on specific forms of Chinese opera, such as chuanqi; jingxi; kunqu; zaju; and nanxi. Sir Donald Francis Tovey (Tovey, Sir Donald Francis)'s article on opera appeared in the 11th edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica (see the Britannica Classic: ).

a drama set to music and made up of vocal (vocal music) pieces with orchestral accompaniment and with orchestral overtures and interludes. In some operas, such as those by Richard Wagner (Wagner, Richard), the music is continuous throughout an act; in others, it is broken up either by recitative (which is more like sung speech) or by dialogue. This article focuses on opera in the Western tradition. For an overview of opera in East Asia (particularly China), see East Asian arts: Dance and theatre (arts, East Asian); see also short entries on specific forms of Chinese opera, such as chuanqi; jingxi; kunqu; zaju; and nanxi. Sir Donald Francis Tovey (Tovey, Sir Donald Francis)'s article on opera appeared in the 11th edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica (see the Britannica Classic: ). The English word opera is an abbreviation of the Italian phrase opera in musica (“work in music”). It names a theatrical form consisting of a dramatic text (libretto, or “little book”) combined with music, usually singing with instrumental accompaniment. Besides solo, ensemble, and choral singers and a group of instrumentalists, the forces performing opera since its inception have often included dancers. A complex, often costly variety of musicodramatic entertainment, opera has attracted audiences for nearly five centuries. Although its supporters have greatly outnumbered its detractors, it has been the target of intense criticism.

The English word opera is an abbreviation of the Italian phrase opera in musica (“work in music”). It names a theatrical form consisting of a dramatic text (libretto, or “little book”) combined with music, usually singing with instrumental accompaniment. Besides solo, ensemble, and choral singers and a group of instrumentalists, the forces performing opera since its inception have often included dancers. A complex, often costly variety of musicodramatic entertainment, opera has attracted audiences for nearly five centuries. Although its supporters have greatly outnumbered its detractors, it has been the target of intense criticism.Charles de Saint-Évremond (Saint-Évremond, Charles de Marguetel de Saint-Denis, Seigneur de), a French man of letters in the 17th century, called it

a bizarre thing consisting of poetry in music, in which the poet and the composer, equally standing in each other's way, go to endless trouble to produce a wretched result.

The 18th-century English statesman and writer Lord Chesterfield (Chesterfield, Philip Dormer Stanhope, 4th earl of) wrote to his son:

As for operas, they are essentially too absurd and extravagant to mention. I look upon them as a magic scene contrived to please the eyes and the ears at the expense of the understanding.

At the opposite extreme of reaction to opera, it has been said that the mere existence of such a masterpiece as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus)'s Le nozze di Figaro (1786; The Marriage of Figaro) suffices to justify Western civilization.

Although the characteristic of opera that most clearly separates it from other theatrical forms is that its principals sing rather than speak their lines, to approach it or criticize it as simply one variety of the musical art is to misjudge it. Its multiple creators almost always have intended an opera to be a lofty and eloquent form of theatrical performance. What commonly differentiates it from other varieties of musicodramatic theatre such as operetta (literally “small opera”) and musical comedy is sobriety of workmanship, density of texture, and (even in operas with comic and farcical librettos) accompanying seriousness of musical tone. On the other hand, some lighter works—by Jacques Offenbach (Offenbach, Jacques), Johann Strauss the Younger (Strauss, Johann, The Younger), W.S. Gilbert (Gilbert, Sir W.S.) and Arthur Sullivan (Sullivan, Sir Arthur), Kurt Weill (Weill, Kurt), George Gershwin (Gershwin, George), and a few others—make neat categorization impossible.

In the preparation of an opera performance, many individual artists and artisans, sometimes spread out across a century or more, necessarily are or have been involved. The first, often unintentional recruit is likely to have been the writer of the original story. Then comes the librettist, who puts the story or play into a form suitable for musical setting and singing, and the composer, who sets that libretto to music. Architects and acousticians will have built an opera house suited or adaptable to performances that demand a sizable stage, a pit to house an orchestra, and a reasonably large audience. A producer-director has to specify the work of designers, scene painters, costumers, and lighting experts. The producer, conductor, and musical staff have to work for long periods with chorus, dancers, orchestra, and extras as well as the principal singers to prepare the performance—work that may last anywhere from a few days to many months. All this does not even take into account the part played by the administrative staff.

Once the complete operatic score—the final libretto and music—is available, what must rule all of those involved is dedication to fulfilling the wishes of the librettist and the composer. Overemphasis or underemphasis of any larger component of an operatic performance can be as damaging to it as off-pitch singing or false entries by instrumentalists. More than one desirable balance between the constituents of performance is often possible. What is certain is that one or another of them must be decided upon, worked toward, and achieved.

The early history

Italian origins

Works in antiquity had combined poetic drama and music. The plays of the ancient Greek dramatists Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides employed choral music in a manner that certainly reflected related usages in earlier times. During the Middle Ages, biblical dramas were commonly accompanied by music and known under various labels, including mystery and miracle plays. These and other related musicodramatic forms may or may not have become collateral ancestors of opera; their descent seems most certain in some 17th-century operas on religious subjects performed in Rome and at several places in Germany. Musical historians and musicologists continue to debate opera's ancestry. The earliest universally accepted direct ancestors of opera appeared in 16th-century Italy. Purely nonreligious works of edifying drama with music, they included intermezzos (intermezzo) and intermedii played between the acts of spoken dramas, with which their purported subject matter often claimed a tenuous connection, and staged ballet. The latter, Italian by birth, achieved a complex, quasi-operatic state in the court ballet (ballet de cour) danced in France late in the 16th century and throughout the 17th; it approached ever closer to opera in the comédie-ballet evolved by Molière and Jean-Baptiste Lully in the 1660s, beginning with Le Mariage forcé (first performed 1664; “The Forced Marriage”).

Musicians, singers, poets, playwrights, and enthusiasts of the literary, musical, and theatrical arts had long cherished a desire for some more formally constituted and more stable form of drama with music, especially in Italy. One response to that expressed desire was the 16th-century madrigal comedy, the singing of dramatic or semidramatic lines (often farcical, and most often with story and characters borrowed from the traditional commedia dell'arte as it had become formalized during the 16th century) in a linked series of more or less discrete madrigals and other varieties of polyphonic song.

But polyphony—the musical texture created by simultaneous, largely unaccompanied singing of interwoven melodies—was by nature alien to theatrical drama: it made extremely difficult, when not impossible, the delineation of individual characters through clearly understandable text. This is noticeable even in the most celebrated of the madrigal comedies, Orazio Vecchi (Vecchi, Orazio)'s paean to the “double Parnassus” of poetry and music, L'Amfiparnaso (first performed in Modena, 1594).

Suitable literary materials

The gestation of opera required the simultaneous availability of a dramatic literary style and a musical texture suitable for incorporation into a new theatrical unity. The essential literary materials had begun to appear in Italy in such chivalresque epics as Ludovico Ariosto (Ariosto, Ludovico)'s Orlando furioso (published complete in 1532) and Torquato Tasso (Tasso, Torquato)'s Gerusalemme liberata (1575), both of which were to be mined for subjects by innumerable opera librettists. More immediately decisive in setting the first direction of opera was one sort of poetic drama: the shorter pastoral writings of 16th-century Italian poets, notably Tasso's L'Aminta (performed 1573) and Battista Guarini (Guarini, Battista)'s Il pastor fido (completed in 1590; The Faithful Shepherd). Idylls or eclogues that had sprung up in the 15th century, such as the Orfeo (staged in Mantua, 1472) of the Italian poet Poliziano ( Politian), were seized on, adapted, and imitated by the composers who had begun to evolve the musical texture essential to the birth of opera and who found apt subjects in the loves, joys, and sorrows of Arcadian shepherds and shepherdesses, often with the intervention of gods, demigods, and heroes.

Until the 1950s it was generally accepted that opera originated with a camerata (a sort of humanistic discussion group) that met in the late 1570s and early 1580s in the Florentine palace of Giovanni Bardi (Bardi, Giovanni, conte di Vernio), count of Vernio. In 1953, however, musicologist Nino Pirrotta showed that the Bardi Camerata, far from having furthered innovation or interested itself in musical drama, was predominantly conservative, often acted in defense of the polyphonic madrigal, and showed no sympathy with the new combinations that would shortly produce opera. In fact, that literary-musical texture was evolved at Florence, but largely among a group of intellectuals, artists, and dilettantes who met informally in the palace of the theatrical theoretician Jacopo Corsi during the 1590s. This latter group also included Emilio del Cavaliere (Cavaliere, Emilio del), the composer, impresario, and choreographer who was to write what is often called the first oratorio, La rappresentazione di anima e di corpo (“The Representation of Soul and Body,” an acted form unlike later oratorios); the singer-composer Jacopo Peri (Peri, Jacopo); and the poet Tasso. Still active at the time, though a little out of favour, was the singer-composer Giulio Caccini (Caccini, Giulio). Corsi and his friends were by no means the first creators of solo vocal lines with instrumental accompaniment, and they shaped their musicotheatrical creations partly in the mistaken belief that their performances were reviving ancient Greek procedures. What, in fact, they did was to take hints from the French court ballet and simultaneously discard polyphony in favour of monody (or homophony)—that is, accompanied singing or recitation on musical tones (recitativo) of one melody at a time. Thus, they ensured both the relative comprehensibility of the words (which to them seemed much more important than the accompanying music) and the use of at least some instrumental support.

An important “manifesto” of the monodic innovators was a collection of short vocal pieces with thorough-bass accompaniment (instrumental chords in sequence as accompaniment to melody) by Caccini, published in 1602: Le nuove musiche (“New Music”), a title that often has been extended to cover the novel musical texture itself. The interaction of these and other Italians with the texture of monody was what finally led, after some false starts, to the emergence not only of opera more or less as it is known today but also of the cantata and the oratorio.

The honour of being deemed the first opera usually is given to a setting by Peri (Peri, Jacopo) of Dafne by the Renaissance pastoral poet Ottavio Rinuccini. It was staged at the Palazzo Corsi in Florence during the pre-Lenten Carnival of 1597–98. The text, divided into a prologue and six scenes, was published in 1600 and therefore survives, but Peri's music (the prologue and one aria excepted) does not. The earliest surviving opera is also Peri's: a setting of Rinuccini's pastoral Euridice, likewise in a prologue and six scenes, which was performed at the Palazzo Pitti in Florence on Oct. 6, 1600.

Monteverdi (Monteverdi, Claudio)

Within 10 years of the premiere of Peri's Dafne at Florence, Mantua heard an opera that is a masterpiece and has been staged frequently in modern times. This was La favola d'Orfeo (“The Fable of Orpheus”), a setting by Claudio Monteverdi (Monteverdi, Claudio) of a poetic text by Alessandro Striggio the Younger. The opera was presented during the carnival of 1607 (the libretto was published then, the score in 1609 and again in 1615). In Orfeo, the accompanying instruments come into their own as a dramatic element: the score contains more than two dozen instrumental pieces. It not only introduces, as a preluding toccata, the idea of the operatic overture but also achieves some sectional unity by repeating brief instrumental numbers (ritornellos). More important, Monteverdi uses recitative expressively and gives it an organizational function by repetitions and developments in predetermined patterns.

Monteverdi continued to compose operas for more than 35 years; meanwhile, the new manner of musicodramatic entertainment spread to other Italian cities. Rome probably first heard an opera as early as 1606, Bologna before 1610. Continuing to employ librettos based on Italian interpretations of Greek and Roman myth, legend, and pseudohistory, writers and composers rapidly swelled the number of operas heard. At Venice in 1643, the 76-year-old Monteverdi created his masterpiece L'incoronazione di Poppea (“The Coronation of Poppea”). Gian Francesco Busenello's superior libretto carried a new note of realism into opera, particularly in the development of human character, and Monteverdi translated it brilliantly into music. Throughout that first period of operatic history, the importance given by composers to emotional drama, to instrumental music, and to structural stability increased along with the capabilities (and pretensions) of singers and the magnificence and complexity of stage settings, stage machinery, and costuming.

Venetian opera

The inauguration early in 1637 of the first opera house open to the general public, the Tron family's Teatro di San Cassiano at Venice, was another decisive factor in establishing opera. That action removed opera from the exclusive hands of royalty and nobility and placed it within reach of all but the poorest sectors of the Italian urban population.

A pupil of Monteverdi, Pier Francesco Caletti-Bruni, known as Francesco Cavalli (Cavalli, Francesco), became the most popular opera composer of his era by furnishing the opera houses of Venice with some 40 operas between 1639 and 1669. Cavalli reacted to the librettos he used with dramatic force and directness. The most renowned of his operas was Giasone (1649; “Jason”), whose libretto by Giacinto Andrea Cocignini included farcical episodes. His chief Venetian rival and successor was Pietro Antonio Cesti (Cesti, Pietro Antonio), about a dozen of whose operas have survived. Some notion of the extravagance to which imitation of Louis XIV's spectacles at Versailles had driven the production of opera elsewhere can be gained from descriptions of the Cesti opera Il pomo d'oro (1667; “The Golden Apple”), composed for the wedding of Emperor Leopold I and Margarita Teresa of Spain in Vienna. Constructed in a prologue and five acts (the third and fifth of which have been lost), with 48 characters, it contained 66 scenes requiring 24 stage settings making use of complex stage machinery. Ballets occurred in every act, and a grand triple ballet brought the opera to its conclusion. Il pomo d'oro provided numerous purely instrumental introductions and interludes, gave relatively little importance to the chorus, skipped rapidly over the essential storytelling recitative, and concentrated on expressive arias and duets.

Venetian opera continued to flourish in the works of such talented theatrical composers as Cavalli, Giovanni Legrenzi, Pietro Andrea Ziani, and Antonio Sartorio. In some details, these Venetian operas reflected the pressures exerted by the tastes and wishes of the paying audiences for which they were designed. Not so lavish with choral interpolations as their Roman contemporaries, the Venetian composers used complex, strong librettos calling for large casts and special lavishness in staging. They also began to develop the melodic profiles that have come to be thought of as particularly Italian. Furthermore, they all but separated the solo aria from the surrounding recitative. They also frequently prefaced and followed solos with purely instrumental music, so continuing the orchestra's elevation from a purely accompanying role. After the middle of the 17th century, the Venetian operatic style began to decline. Among the later Venetian operatic composers of talent and fame were Antonio Lotti, Carlo Francesco Pollaroli, Antonio Vivaldi (Vivaldi, Antonio), and Baldassare Galuppi (Galuppi, Baldassare), whose name became associated with opera buffa.

Development of operatic styles in other Italian cities

Several Italian cities soon developed recognizable operatic styles. At Rome, for example, a group of composers tended toward unified structure, gave ensemble and choral song expanded roles, and increased the difference between the solo (aria) and the Florentine type of continuous recitative by allowing arias to interrupt dramatic progress in order to express or comment upon emotional moods. These 17th-century Roman composers, including Stefano Landi, Domenico Mazzocchi, Luigi Rossi, and Michelangelo Rossi, also used comic episodes to lighten prevailingly tragic stories (as did the Venetians). They concentrated attention productively on instrumental overtures and on overturelike pieces preceding acts or sections of acts. Two Roman composers—Domenico Mazzocchi's brother Virgilio and Marco Marazzoli—often are cited as having created the first completely comic opera, Chi soffre speri (1639; “He Who Suffers, Hopes”). Its libretto was written by Giulio Cardinal Rospigliosi, who was to be elevated to the papacy in 1667 as Clement IX. The invited guests at its first performance, in the Palazzo Barberini, included English poet John Milton and Giulio Mazarini, the future Cardinal Mazarin, statesman to Louis XIV.

In the 18th century the centre of Italian opera shifted to Naples. With some exceptions, the earliest unmistakably Neapolitan operas changed their focus back from the music to the words. Two of its instigators were dramatic poets: Apostolo Zeno, born a Venetian, and the Roman Pietro Trapassi, known as Metastasio (Metastasio, Pietro)—perhaps the greatest of the 18th-century librettists. Continuing the custom of basing librettos on Greco-Roman legend and pseudohistory (but dispensing almost entirely with classical mythology), Zeno and Metastasio wrote texts of formal beauty and linguistic clarity, preferring solemn, usually tragic subjects ( opera seria) in three acts to comic episodes and characters. The aria came to dominate, and the use of chorus declined.

The term Neapolitan opera also came to indicate harmonically naïve, melodious lighter operas in the gallant tone of the Rococo style; the rich development of the bel canto styles (where beautiful singing per se was predominant), signifying supreme vocal agility and smoothness that was supplied first by castrati (castrato), men who had been castrated before puberty in order to preserve the high ranges of their boyish voices; and the appearance of the centone or pasticcio (pastiche), a libretto set to a score made up of music borrowed either from scores (then uncopyrighted or otherwise legally protected) of several composers or from several operas by a single composer. The role of the orchestra diminished. But perhaps the most discussed feature that particularly designated Neapolitan opera was the aria da capo, an aria in three sections, the third part repeating the first. The form had appeared in northern Italy early in the 17th century but was employed with comparative infrequency there. Some Neapolitan operas, however, consisted of 20 or more da capo arias separated by a minimum of story-advancing recitative (narrative passages in which the vocal line proceeds in speechlike rhythm and simple melody).

A masterly operatic composer of the transitional style who bridged the era between the Baroque and the pre-Classical Neapolitan style was Alessandro Scarlatti (Scarlatti, Alessandro). In his many operas Scarlatti triumphed, by the strength of musical imagination, over librettos that were intended to provide vehicles for phenomenally trained singers and therefore reduced attention to the drama. Notable among Scarlatti's immediate successors were such composers as Nicola Antonio Porpora, Leonardo Vinci (Vinci, Leonardo), and Leonardo Leo (Leo, Leonardo).

In 1720 the Venetian composer-poet-statesman Benedetto Marcello (Marcello, Benedetto) published a mordant satire on the increasingly rigid and undramatic conventions that had taken hold of opera seria: Il teatro alla moda, o sia metodo sicuro e facile per ben comporre ed eseguire opere italiane in musica (“The Theater à la Mode, or The Secure and Easy Method of Composing and Performing Italian Operas”). The distress that it and other criticisms brought resulted in an improved genre, still in effect opera seria but showing attempts at reform of its mannerisms. Representative composers within the short “reform” movement were the mid-18th-century composers Niccolò Jommelli (Jommelli, Niccolò) and Tommaso Traetta. A more intellectually rigorous reformation was undertaken consciously by Christoph Willibald Gluck (Gluck, Christoph Willibald) in collaboration with the librettist Ranieri Calzabigi (Calzabigi, Ranieri), beginning with Orfeo ed Euridice (1762).

comic opera

Comic opera meanwhile had expanded from its shadowy existence within and between the acts of opera seria. From the early, tentative efforts of several 17th-century Roman and Florentine composers, it had moved into a bustling, rude, independent vitality of its own, often in the form of satirical opera buffa (Italian: “comic opera”), generally shaped in two acts rather than the usual three of opera seria. Expelled from the precincts of opera seria by the librettos of Zeno and Metastasio, the comic spirit had taken refuge in such an expanded intermezzo as La serva padrona (1733; The Maid Mistress), by Giovanni Battista Pergolesi (Pergolesi, Giovanni Battista). When it matured, the style borrowed back some of the more serious emotional qualities of opera seria, often including “serious” roles interspersed among the comic ones. This led to a hybrid nature in many operas, including two works using librettos derived from the plays of Pierre de Beaumarchais (Beaumarchais, Pierre-Augustin Caron de)—Il barbiere di Siviglia (1782; The Barber of Seville), by Giovanni Paisiello (Paisiello, Giovanni), and Mozart's Le nozze di Figaro (1786; The Marriage of Figaro)—as well as Il matrimonio segreto (1792; The Secret Marriage), by Domenico Cimarosa (Cimarosa, Domenico).

One of the determining characteristics of this mixed style was the elaboration of ensemble numbers concluding acts. These operas dispensed almost entirely with the magnificent display and grandeur of staging increasingly required of opera seria. Perhaps the major drawback of the mixed style was that the best serious librettists did not write texts for opera buffa.

Early opera in France

Opera was imported into France from Italy well before 1650, but it long failed to take firm hold there with royal and other audiences, at first having to compete on unequal terms with the spoken drama (often with musical interludes) and the ballet. The Pomone (1671) of Robert Cambert (Cambert, Robert), to a pastoral libretto by Pierre Perrin, is commonly called the first French opera. Its premiere almost certainly inaugurated the Académie Royale de Musique (now the Paris Académie de Musique or Paris Opéra) on March 3, 1671. Only fragments of the music of Pomone still exist.

Jean-Baptiste Lully (Lully, Jean-Baptiste) made opera a French art. This talented and shrewd composer borrowed freely from both the spoken French drama and the court ballet. Though himself an Italian, he played down the extended, formalized Italian aria in favour of shorter, more instantly captivating “airs.” He formed recitative after the declamatory manner of the Comédie-Française theatre company and also evolved the “French overture” (a stately slow introduction followed by a quick fugal section), as distinct from the “Italian overture” (a three-part structure, fast-slow-fast). His operas and those of his imitators and followers assigned great importance to dancing, choruses, instrumental interludes, and a dazzlingly complex stage setting. Lully became the virtual dictator of music in France partly because of the strengths of his literary collaborators—first the dramatist Molière in comédie-ballet and then the fine librettist Philippe Quinault.

The pervasive Lullyan style, altered surprisingly little except in the direction of still more imposing grandeur, attained its culmination in the magnificent operas of Jean-Philippe Rameau (Rameau, Jean-Philippe), especially in his Hippolyte et Aricie (1733; libretto by Simon-Joseph de Pellegrin), Les Indes galantes (1735; “The Courtly Indies,” libretto by Louis Fuzelier), and, particularly, Castor et Pollux (1737; libretto by Pierre-Joseph-Justin Bernard), which was performed at the Paris Opéra 254 times in 48 years. Except for the special instance of Les Indes galantes, which was billed as a ballet-héroïque, Rameau's chief operas were each divided into a prologue and five acts, a pattern that many later French composers favoured. Rameau, like virtually every other French opera composer, set the language to music with such probity and clarity that it can be understood properly when sung. His operatic works are regarded widely as the apogee of 18th-century French opera.

Early opera in Germany and Austria

Although Heinrich Schütz (Schütz, Heinrich) composed Dafne, the first known opera with a German text, and heard it played at Torgau on April 23, 1627, the active history of opera in Germany began with the Italian composers residing there. A remarkable Venetian composer-diplomatist-ecclesiastic, the Abbé Agostino Steffani (Steffani, Agostino), carried much of his native city's early operatic manner to Munich, Hanover, and other German centres. He began his operatic production with Marco Aurelio (first performed in Munich, 1681) and continued thereafter to compose operas for 28 years. In his use of both Italian and French procedures, particularly in handling overture and recitative, Steffani evolved a sort of international Italian style that clearly influenced other “transplanted” composers.

For the next 100 years the influence of Italian opera was so pervasive that even native German composers adopted the Italian operatic style and used texts in Italian.

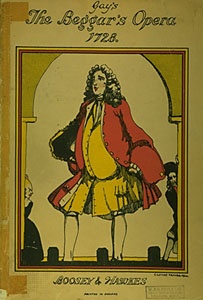

The German word Singspiel was originally used for all sorts of opera. The earliest known entertainments so designated were composed by a pupil of Heinrich Schütz, Johann Theile. One of them, Adam und Eva, inaugurated the Hamburg Opera in 1678. During the mid-18th century, the term singspiel came to be reserved for what the English called “ ballad opera,” the French opéra comique (opéra-comique): light, usually comic operas that incorporated spoken dialogue. The comic singspiel of the 18th century was born with The Devil to Pay (London, 1731) and its sequel, The Merry Cobbler (London, 1735), English ballad operas with texts by Charles Coffey. These had pasticcio (assembled) scores capitalizing, not very successfully, on the great popularity of The Beggar's Opera (1728), which had a text by John Gay (Gay, John) and a pasticcio score brought together by John Christopher Pepusch (Pepusch, John Christopher). The Coffey texts having been translated into German, scores were composed to them by J.C. Standfuss as Der Teufel ist los (first performed 1752) and Der lustige Schuster (first performed 1759); they later were restaged as arranged by Johann Adam Hiller (Hiller, Johann Adam), who also composed several other singspiels and brought to culmination what came to be known as the Leipzig School. Both Berlin and Vienna inevitably took up the singspiel, and the form held the interest of major composers well into the 19th century.

The German word Singspiel was originally used for all sorts of opera. The earliest known entertainments so designated were composed by a pupil of Heinrich Schütz, Johann Theile. One of them, Adam und Eva, inaugurated the Hamburg Opera in 1678. During the mid-18th century, the term singspiel came to be reserved for what the English called “ ballad opera,” the French opéra comique (opéra-comique): light, usually comic operas that incorporated spoken dialogue. The comic singspiel of the 18th century was born with The Devil to Pay (London, 1731) and its sequel, The Merry Cobbler (London, 1735), English ballad operas with texts by Charles Coffey. These had pasticcio (assembled) scores capitalizing, not very successfully, on the great popularity of The Beggar's Opera (1728), which had a text by John Gay (Gay, John) and a pasticcio score brought together by John Christopher Pepusch (Pepusch, John Christopher). The Coffey texts having been translated into German, scores were composed to them by J.C. Standfuss as Der Teufel ist los (first performed 1752) and Der lustige Schuster (first performed 1759); they later were restaged as arranged by Johann Adam Hiller (Hiller, Johann Adam), who also composed several other singspiels and brought to culmination what came to be known as the Leipzig School. Both Berlin and Vienna inevitably took up the singspiel, and the form held the interest of major composers well into the 19th century.The most important opere serie composed in Germany during the early 18th century were created for the Hamburg Opera, at which both Reinhard Keiser (Keiser, Reinhard) and, for a brief interval, the young George Frideric Handel (Handel, George Frideric) worked. Keiser composed more than 125 operas, mostly to German texts. Of Handel's large operatic output, only two works with Italian texts—Almira and Nero (both 1705, the second now lost)—were staged during his Hamburg stay. Keiser doggedly tried to attract the widest possible public. His operas often succeeded in charming audiences, but most of them have vanished; those that survive demonstrate a skillful exploitation of the orchestra, particularly in the telling use of solo instruments in the accompaniment of arias.

Handel went from Italy to England in 1710. In London, with the opera Rinaldo (1711), he began 30 years of stubborn dedication to the traditions of Neapolitan opera seria. He created a dozen or more of the most inspired operas of the first half of the century, including Giulio Cesare (1724; “Julius Caesar”), Rodelinda (1725), Orlando (1733), and Alcina (1735). Handel transcended the formal style of opera seria by his melodic inspiration, harmonic daring, and varied characterization.

German by birth, but almost wholly Italianate by disposition, Johann Adolph Hasse (Hasse, Johann Adolph) successfully carried on the Metastasian traditions of opera seria in a large number of operas set to Italian texts. The Italian contours of his best melodies, supported by adventurousness in harmonic placement and in instrumentation, did almost as much as Handel's operas to prolong the glory of the Italian tradition.

From the “reform” to grand opera

The “reform”

Christoph Willibald Gluck (Gluck, Christoph Willibald) has become an ambivalent figure in the evolution of opera: he has been loosely and often incorrectly categorized, and both praised and condemned, for mistaken reasons. His operas that he composed to Italian texts up to about 1756 were conventional settings of Metastasian librettos. After settling in Vienna in 1750, though not abandoning the composition of traditional opere serie in Italian, Gluck began to react to the French operatic styles popular there. At first he merely added a few new numbers to one-act opéras comiques taken to Vienna from Paris, which he arranged and conducted for the court at Schönbrunn and Laxenburg. Then he began to compose similar operas in French.

Thanks to the enthusiasm of the superintendent of the imperial Vienna theatres, Conte Giacomo Durazzo, Gluck had been absorbing the example of the outstanding French dancer-choreographer Jean-Georges Noverre (Noverre, Jean-Georges). Seminal in Noverre's call for reform was the insistence that a ballet not be left as a simple collection of unconnected episodes but be shaped into a mimed dance drama. Gluck then composed the ballet Don Juan (1761), the earliest of his scores to place him among the great composers. In the same year, a very talented poet-librettist-adventurer, Ranieri Calzabigi (Calzabigi, Ranieri), reached Vienna from Paris. Falling in with the anti-Metastasian intellectuals spearheaded by Durazzo, Calzabigi thereafter brought his acquaintance with Rameau's stately operas to the writing of three librettos for Gluck, for whose signature he also drew up the renowned dedication of the publication of the Calzabigi-Gluck Alceste in 1769. That dedication—a manifesto, really—is the central document of “operatic reform,” summing up one side of the unending debate between supporters of the primacy of the opera libretto and supporters of the primacy of the music. The Alceste dedication emphasized that superfluous, florid da capo arias were to be dispensed with; simplicity of expression and emotional truth were to take their place.

Although some of the most accomplished composers of opera certainly would not have agreed that, as Calzabigi-Gluck stated, the “true office” of music is “serving poetry,” and though a strict obedience to all the precepts of the Alceste dedication would have impoverished much of the richest operatic music (Gluck himself did not follow them rigorously), the pronouncement unquestionably summoned opera back temporarily to its function as musicotheatrical drama. The most significant results of the attitudes it expressed were the magnificent Calzabigi-Gluck operas first staged in Vienna: Orfeo ed Euridice (1762), Alceste (1767), and Paride ed Elena (1770; “Paris and Helen”). The two earliest of these became even more stately and Rameau-like when Gluck reconstituted them to French librettos for Parisian audiences.

Gluck was at the height of his achievement in Iphigénie en Aulide (1774; “Iphigenia in Aulis,” libretto adapted from Racine's tragedy by Bailli du Roullet) and in his masterpiece Iphigénie en Tauride (1779; “Iphigenia in Tauris,” libretto adapted from Euripides by Nicholas-François Guillard). Gluck's extraordinary power at his best derives from a lean sparseness of means—particularly of harmonic density, with the result that the smallest shifts arrive with great power—and the ability to make the most of the dramatic strengths of the often excellent librettos he used.

Gluck had some immediate followers and imitators, notably Antonio Salieri (Salieri, Antonio), who gave lessons to Ludwig van Beethoven, Franz Schubert, and Franz Liszt and was friendly with both Joseph Haydn and Gioachino Rossini. Another, belated, Gluckian was Gluck's onetime “rival” in a Parisian polemic “war,” Niccolò Piccinni (Piccinni, Niccolò), whose greatest work was Didon (1783; libretto by Jean-François Marmontel (Marmontel, Jean-François)). Finally, there was Antonio Sacchini, remembered chiefly for his Oedipe à Colone (1786; “Oedipus at Colonus,” libretto by Nicolas-François Guillard). On the highest level, however, the Gluckian “reform” produced only his own masterpieces, although it led indirectly to certain of the operas of Gaspare Spontini (Spontini, Gaspare), particularly La Vestale (first performed 1807; “The Vestal Virgin”), and Luigi Cherubini (Cherubini, Luigi), particularly Médée (1797; “Medea”). In part, Gluck also influenced the vast achievement of Hector Berlioz (Berlioz, Hector) in Les Troyens (1856–58; “The Trojans”).

Opera in England

Just as immediate acceptance of opera had been made difficult in France by the entrenched ballet and the 17th-century drama of Jean Racine (Racine, Jean) and Pierre Corneille (Corneille, Pierre), so it was delayed in England by the court masque, an aristocratic 16th- and 17th-century entertainment derived largely from ballet. Most often dealing with allegorical and mythical subjects, the masque mixed poetic text, instrumental and vocal music, dancing, and acting. The most familiar masque is Comus (text by John Milton (Milton, John) and music by Henry Lawes (Lawes, Henry)), which was staged at Ludlow Castle in 1634. Many other embryonic operas were produced in the middle decades of the 17th century, often being more like plays with incidental music. The first English opera was Dido and Aeneas (1689), by Henry Purcell (Purcell, Henry). This musical masterpiece, with libretto by a future poet laureate, Nahum Tate (Tate, Nahum), contains one of the earliest operatic arias to remain in the repertoire: Dido's lament, "When I Am Laid in Earth." In this opera, Purcell succeeded in writing a real, albeit brief, music drama, breaking down the formal barriers between recitative and song.

England, however, was not ready for opera. Although later Purcell works, including King Arthur (1691), The Fairy Queen (1692), and The Indian Queen (1695), have been called operas, they were actually suites of incidental music for plays. No other comparable composer in England turned his attention to opera, and soon the rage for Italian opera (particularly when the singers included a good castrato) effectively barred that road to English composers. The arrival of Handel (Handel, George Frideric) from Italy in 1710 decided the direction of opera in London for many decades. Beginning in 1711 with Rinaldo (libretto by Giacomo Rossi, indirectly derived from Tasso's epic Gerusalemme liberata) and continuing intermittently until Deidamia (libretto by Paolo Rolli) in 1741, Handel provided English audiences with his own remarkable brand of opera seria, acting as both composer and, most often, impresario. The greatest composer of opera in his age, Handel eventually outlasted his popularity in London's opera houses and turned to the creation of a magnificent series of oratorios set to English texts. His operatic reign was challenged at its height only by a faction that set up the gifted Modenese composer Giovanni Bononcini (Bononcini, Giovanni) in an unequal battle against him. Handel's operas all but vanished from the repertoire in the 19th century, but they were increasingly revived after the 1920s and had become a staple of opera companies and music conservatories by the end of the 20th century.

An event that contributed to the defeat of Handel as an opera impresario was the London production in 1728 of The Beggar's Opera. That bawdy, rollicking satire in English became phenomenally popular and spawned a family of imitations that finally accustomed audiences in London and elsewhere in the British Isles to hearing a staged play sung in the vernacular.

Viennese masters

Italian opera buffa strongly attracted Viennese audiences, and Austrian composers were naturally influenced by it. Perhaps the most interesting of the Vienna-born composers of 18th-century comic opera was Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf (Ditters von Dittersdorf, Carl), whose Italianate Doktor und Apotheker (1786; “Doctor and Druggist,” libretto by Gottlieb Stephanie), though successful and lively, was overshadowed by the contemporary works of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

Joseph Haydn (Haydn, Joseph) composed about 20 musicodramatic scores: a singspiel, five short operas for marionettes, and several Italianate opere buffe and opere serie for private performance in the Eisenstadt palace theatre of his employer-patrons, the Esterhazy princes. Several of Haydn's operas have had modern revivals, including Il mondo della luna (1777; “The World of the Moon,” libretto by Carlo Goldoni (Goldoni, Carlo)), L'isola disabitata (1779; “The Deserted Island,” libretto by Metastasio), and La fedeltà premiata (1780; “Faithfulness Rewarded,” libretto by Giovanni Battista Lorenzi).

Vienna was to be one of the centres of the operatic career of Mozart (Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus), one of the greatest masters of opera. Mozart began to write theatrical music when only 10 years old and brought out the first of his important operas at Munich in 1781, when he was only 25. This was Idomeneo. Its libretto, by Giambattista Varesco, is an imitation of Metastasio's style. But Mozart rose above the conventional operatic patterns and filled them with richly expressive music so that the result is scarcely recognizable as an opera seria. As a work of musical art, Idomeneo ranks as the supreme Italian opera seria of the late 18th century.

Vienna was to be one of the centres of the operatic career of Mozart (Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus), one of the greatest masters of opera. Mozart began to write theatrical music when only 10 years old and brought out the first of his important operas at Munich in 1781, when he was only 25. This was Idomeneo. Its libretto, by Giambattista Varesco, is an imitation of Metastasio's style. But Mozart rose above the conventional operatic patterns and filled them with richly expressive music so that the result is scarcely recognizable as an opera seria. As a work of musical art, Idomeneo ranks as the supreme Italian opera seria of the late 18th century.One year after Idomeneo, Mozart wrote a masterly, charming singspiel to a German text: Die Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Seraglio, libretto by Christoph Friedrich Bretzner as edited by Gottlieb Stephanie). A sentimental farce full of immediately attractive music and graced with a fine part for a comic bass (Osmin), Die Entführung also contains in "Martern aller Arten" (“Torments of all Kinds”) a soprano aria so extensive in plan and difficult to sing that it has challenged the foremost sopranos of every era. The opera has been called the greatest of all truly comic singspiels, and it is notable for the seriousness with which it treats the relationship between its two principal characters and for its noble aspirations.

Mozart's next completed full-scale opera is one of the treasures of Western civilization, the greatest of all seriocomic operas, Le nozze di Figaro (1786; The Marriage of Figaro). In addition to its purely musical beauty, this work shows Mozart to be a creator of individual characters of almost Shakespearean calibre; he goes far beyond the opportunities offered by his able librettist and creates, by musical means, believable, rounded human beings, often employed in ensembles as well as in solos and in elaborately constructed finales.

Mozart's next opera, written for Prague, was Don Giovanni (1787; libretto by Da Ponte, based on earlier Don Juan librettos and other writings related to plays by Tirso de Molina, Thomas Corneille (Corneille, Thomas), and others). Writers in the 19th century tended to regard Don Giovanni as the greatest opera ever composed, in part because musical elements in it foretold operatic Romanticism. Yet aspects of Da Ponte's libretto disturbed some 20th-century critics—particularly the grim, though justifiable, ending of what up to then has been a comedy, followed by the then-conventional postlude, during which the singers step out of character to underline the story's moral. Musically, Don Giovanni shares many of the virtues of Le nozze di Figaro, in beauty, in characterization, and in dramatic power.

In his last collaboration with Da Ponte, Mozart created another opera buffa, Così fan tutte (1790; “All Women Are like That”). This is an opera of flawless workmanship reconciled with the dramatic claims of a seemingly artificial and cynical libretto, which in fact exposes human foibles. Although it was not a success at first, it came to be judged as one of Mozart's greatest stage works.

In 1791, returning to the singspiel in German, Mozart composed Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute; libretto by Emanuel Schikaneder), an allegorical and Masonic opera with a seemingly nonsensical but in fact elaborately significant libretto in strong contrast with Così fan tutte's cynicism about women. Here Mozart created some of the most radiantly beautiful music ever composed, assigning it lavishly to both the serious and the comic, both the admirable and the vicious characters.

Like Die Zauberflöte, Beethoven (Beethoven, Ludwig van)'s Fidelio (1805, revised 1806 and 1814) rose above the limitations of the singspiel pattern, becoming something bigger and grander. The libretto has never satisfied anyone entirely, and some of the vocal lines seem more suitable for instruments than voices. Yet the grandeur of much of the Fidelio music and the admirability of the central character (Leonore, who—taking a great risk—disguises herself as a young man, Fidelio, in order to rescue her husband from political incarceration in a dungeon) irradiates the opera throughout. Its theme of the triumph of the human spirit over oppression has helped secure Fidelio's place among the world's most beloved operas.

France, 1752–1825

In the early 1750s political changes and intense intellectual discussion led to a polemic “war”—the guerre (or querelle) des bouffons (“war 【quarrel】 of the buffoons”). This was a mainly literary confrontation of the solemn past of opera seria and tragédie lyrique with the farce and sentiment of opera buffa, though many of the writers saw it in nationalistic terms. It had a happy outcome: the subsequent composition by both French composers and resident foreigners of excellent examples of opéra comique (opéra-comique), which became a French version of the English ballad opera, the German singspiel, and the Italian opera buffa.

In 1752, the year of the first battles of the guerre des bouffons, Jean-Jacques Rousseau (Rousseau, Jean-Jacques) staged at Fontainebleau his one-act comic opera Le Devin du village (“The Village Soothsayer”). The libretto was his own. In the score he brought together, in the pasticcio manner, melodies reflecting the very popular romances and vaudevilles being heard at the Paris fairs. It pleased battlers on both sides of the operatic war, being very French in manner and sentiment but Italian in being through-composed (continuously set) and employing recitative. Rousseau hoped to establish this combination as a standard for French comic opera, but his plan was not immediately successful. In 1755, however, a Naples-trained Italian, Egidio Duni, settled in Paris and began to compose (or perhaps, at first, merely to assemble) opéras comiques. French and Belgian composers gladly adapted the new variety of opéra comique (not always with comic subject matter) and soon established its reign in the Paris and provincial theatres; nearly all of these composers created other sorts of musicodramatic works as well. Among them, several names stand out, together with the finest or most renowned of their operas. One of the most interesting of these opéra comique composers was François-André Danican, called Philidor (Philidor, François-André), also a famous chess player, who wrote about 20 opéras comiques.

More sentimental—in fact, tending toward the tenderly tearful—was Pierre Alexandre Monsigny, never thoroughly trained in music but able to create winning melodies and to exploit for dramatic purpose the timbres of individual instruments. Probably the finest of the 18th-century composers of opéra comique was a Belgian, André Grétry (Grétry, André-Ernest-Modeste), who most happily balanced the French and Italian styles. He was a very original and extremely productive composer over a 30-year period spanning the French Revolution.

Étienne-Nicolas Méhul (Méhul, Étienne-Nicolas), who used opéra comique conventions including spoken dialogue, also had a career spanning the Revolution. Influenced by Gluck, Méhul had composed numerous works in many genres when, in 1807, he produced his masterpiece, Joseph, which is a rarity among operas in several ways: its libretto, by Alexandre Duval, is derived from the Bible, a source of drama usually reserved for the oratorio; it has no female characters; and it mixes the most solemn classicism with the sentiment of the popular romances.

Early in the 19th century, French opéra comique achieved a new equilibrium in the best works of François-Adrien Boieldieu (Boieldieu, François-Adrien). He won truly astonishing—and, to several composers (Berlioz included), maddening—popularity with La Dame blanche (1825; “The White Lady,” libretto by Eugène Scribe (Scribe, Eugène), based upon Sir Walter Scott (Scott, Sir Walter, 1st Baronet)'s novels Guy Mannering 【1815】 and The Monastery 【1820】). There were 1,669 performances of this work at the Opéra-Comique in Paris between 1825 and 1926.

Le Pré aux clercs (1832; “The Field of Honour,” libretto by François de Planard), the most accomplished opera of Louis-Joseph-Ferdinand Hérold (Hérold, Ferdinand), all but equaled the popularity of La Dame blanche; it had received 1,600 performances at the Paris Opéra-Comique by 1939. Hérold's other outstanding success was Zampa (1831; libretto by Anne-Honoré Mélesville), which became vastly popular in Germany. An extraordinarily prolix composer, Hérold never succeeded in working out a dependable, unified manner of his own. Opéra comique after Boieldieu became more Italianized, reflecting very largely Gioachino Rossini (Rossini, Gioachino)'s influence.

Italy in the first half of the 19th century

The splendid musical achievements of the classical Viennese style during the late 18th and early 19th centuries threatened to leave Italy, opera's native home, out of the operatic mainstream. Two accidents—one the voluntary expatriation to northern Italy of a German, Simon Mayr (Mayr, Simon), and the other the unpredictable eruption of a genius, Gioachino Rossini—saved the day for Italian opera in Italy and outside it.

Mayr, known in Italy as Giovanni Simone Mayr, composed nearly 70 operas in Italian between his first (1794) and his last (1815). He appears to have been influenced deeply by Mozart; he demonstrated a keen dramatic sense, a sophisticated grasp of the conventions of opera seria, and a varied use of the orchestra (particularly of solo woodwinds and French horns). Many of his operas were for a long time extremely popular throughout Italy, and his immediate influence was beneficial, particularly on the practice of his most famous pupil, Gaetano Donizetti (Donizetti, Gaetano), and on Saverio Mercadante (Mercadante, Saverio).

The operas of Nicola Zingarelli (Zingarelli, Nicola Antonio) and of Ferdinando Paer (Paer, Ferdinando) were transitional, between Classical and grand opera in mode and manner. Zingarelli's conventional opere buffe displayed a genuine humour and some liveliness of musical imagination; his most enduringly performed work, however, was an opera seria, Giulietta e Romeo (1796; “Juliet and Romeo,” libretto by Giuseppe Maria Foppa). He is now remembered chiefly as a teacher of Vincenzo Bellini (Bellini, Vincenzo). Paer, who composed more than 40 operas, worked mostly in Vienna, Dresden, and Paris; his musical style changed with his surroundings.

The production at Venice in 1810 of the first performed opera of Rossini (Rossini, Gioachino), La cambiale di matrimonio (“The Bill of Marriage”; libretto by Gaetano Rossi), announced a new operatic genius. Into the genteel, often charming atmosphere of lingering 18th-century operatic manners, Rossini brought genuine originality marked by rude wit and humour and an entire willingness to sacrifice all “rules” of musical and operatic decorum. Both his opere buffe and his opere serie soon became so popular throughout Italy and then throughout the Western world that they all but blotted out his unfortunate contemporaries—Donizetti and Bellini excepted.

Rossini's dazzling career marked the zenith of the bel canto style, a singer-dominated manner of composition (and at times improvisation) that played to audiences' delight in vocal agility, smoothness of voice, and long, florid phrasing. From the period of Rossini's greatest Italian triumphs (he had a second career in Paris), and of Donizetti and Bellini, come the names of legendary voices such as Isabella Colbran (Rossini's first wife), Giuditta Pasta (Pasta, Giuditta), Maria Malibran (Malibran, Maria), Giovanni Battista Rubini (Rubini, Giovanni Battista), and Luigi Lablache (Lablache, Luigi). For appearances by these singers, composers altered their scores; when they sang, they interpolated extraneous arias that displayed their prowess. Rossini tried to insist that his operas be sung as he himself composed or revised them, but it was a losing battle. The polished artistry and extreme technical training and technique of such singers, as well as their extraordinarily wide ranges, have left performance of the bel canto operas an enduring challenge for singers.

Rossini's most famous opera is Il barbiere di Siviglia (1816; The Barber of Seville, based on the libretto by Cesare Sterbini after the 18th-century play by Beaumarchais), the most nearly flawless of all opere buffe. Several others among his comedies rank only a little lower in musical invention, genuine comic brio, and opportunities for trained singers of vocal display and for farcical characterization: L'Italiana in Algeri (1813; “The Italian Girl in Algiers,” libretto by Angelo Anelli), Il Turco in Italia (1814; “The Turk in Italy,” libretto by Felice Romani), and La cenerentola (1817; Cinderella, libretto by Jacopo Ferretti). Rossini prefaced several of these operas with swift, witty overtures that have held a place in the repertoire of symphony orchestras.

His first serious work was Otello (1816; libretto by Francesco di Salsa). But it was only in his Parisian pieces, such as Semiramide (1823; libretto by Gaetano Rossi), Le Siège de Corinthe (1826; libretto by Alexandre Soumet and Luigi Balocchi), and Guillaume Tell (1829; William Tell, libretto by Étienne de Jouy and Hippolyte Bis), his last opera, that his talent for works on a bigger scale found its full flowering. Some of these later operas owe their revival in the middle of the 20th century to the appearance of a few singers able to project meaningfully their difficult vocal lines.

Gaetano Donizetti (Donizetti, Gaetano) first composed a series of well-made, largely undistinguished operas but gradually developed dramatic strength, more memorable melody, and a forceful deployment of the orchestra for theatrical drama. In 1830, the year after Rossini's farewell to operatic composition, Donizetti produced at Milan Anna Bolena (“Anne Boleyn”), with a libretto by Felice Romani, who worked with many opera composers of the time. It immediately placed him with Bellini as an inevitable successor to Rossini. What became clear only in retrospect was that it also showed him to be the most important immediate predecessor of Giuseppe Verdi (Verdi, Giuseppe). Donizetti clung to the long, legato (smoothly flowing) melodies and the ornamented vocal lines of bel canto, but he also unmistakably foreshadowed Verdi's dramatic vigour and many of the younger man's compositional methods. Several apparently unconscious borrowings from Donizetti have been noted by students of Verdi's operas.

Like Rossini, Donizetti moved freely back and forth between serious and comic subjects. He composed about 70 stage works in 25 years. After the success of Anna Bolena, he composed, with speed and facility that remain astonishing, numerous operas of enduring quality. They include the sentimental comedy L'elisir d'amore (1832; “The Elixir of Love,” libretto by Felice Romani); the popular Lucia di Lammermoor (1835; libretto by Salvatore Cammarano, derived from Sir Walter Scott (Scott, Sir Walter, 1st Baronet)'s The Bride of Lammermoor, 1819), an opera that reflects Donizetti's acquaintance with the music of Bellini; the delightful opéra comique La Fille du régiment (1840; The Daughter of the Regiment, libretto by Jules-Henri Vernoy de Saint-Georges and Jean-François-Alfred Bayard); the grand opera La Favorite (1840; libretto by Alphonse Royer, Gustave Vaëz, and perhaps Scribe); and—judged by many to be Donizetti's masterwork—the ever fresh and vivid opera buffa Don Pasquale (1843; libretto by Giacomo Ruffini and Donizetti).

Like Rossini, Donizetti moved freely back and forth between serious and comic subjects. He composed about 70 stage works in 25 years. After the success of Anna Bolena, he composed, with speed and facility that remain astonishing, numerous operas of enduring quality. They include the sentimental comedy L'elisir d'amore (1832; “The Elixir of Love,” libretto by Felice Romani); the popular Lucia di Lammermoor (1835; libretto by Salvatore Cammarano, derived from Sir Walter Scott (Scott, Sir Walter, 1st Baronet)'s The Bride of Lammermoor, 1819), an opera that reflects Donizetti's acquaintance with the music of Bellini; the delightful opéra comique La Fille du régiment (1840; The Daughter of the Regiment, libretto by Jules-Henri Vernoy de Saint-Georges and Jean-François-Alfred Bayard); the grand opera La Favorite (1840; libretto by Alphonse Royer, Gustave Vaëz, and perhaps Scribe); and—judged by many to be Donizetti's masterwork—the ever fresh and vivid opera buffa Don Pasquale (1843; libretto by Giacomo Ruffini and Donizetti).Altogether different from either Rossini or Donizetti was Vincenzo Bellini (Bellini, Vincenzo). His operas have come to seem the natural habitat of bel canto, of the unchallenged supremacy of vocal melody in amazingly long-breathed and highly decorated lines. Only his first student opera contains even a trace of humour. He and his librettists filled their collaborations with intensely amorous and other subjective emotion, ethical confrontations, and usually tragic involvements. Bellini cultivated with meticulous care his unrivaled gift for convincingly melancholy melody, especially in arias and duets; he gave much less attention to ensembles, choruses, and the expressive potentialities of the orchestra.

Beginning in 1827 with Il pirata (“The Pirate,” libretto by Felice Romani, who thereafter supplied all of Bellini's librettos except that for I puritani), Bellini made his presence felt throughout Italy and then gradually throughout Europe and the Americas. In 1831 two of Bellini's enduring masterworks were produced: the pastoral opera semiseria La sonnambula (The Sleepwalker) and the heroic tragedy Norma. In the last year of his life, he won another triumph with an opera very loosely connected with Cromwellian times in England, I puritani (1835; “The Puritans,” libretto by conte Carlo Pepoli).

Unlike Rossini and Donizetti, Bellini exercised little or no influence upon the style of his successors. With these three men, both the late period of bel canto and the second period of opera buffa drew to a close. After the onset of Donizetti's crippling illness in 1847, the Italian opera houses in Italy, Paris, London, and elsewhere could look to Giuseppe Verdi.

Grand opera and beyond

French grand opera

Nineteenth-century Paris was to foster and witness the birth of “grand opera,” an international style of large-scale operatic spectacle employing historical or pseudohistorical librettos and filling the stage with elaborate scenery and costumes, ballets, and phalanxes of supernumeraries. Dispensing almost entirely with the delicacies of bel canto, it vastly enlarged both the orchestra itself and its role in the dramatic happenings. Grand opera naturally had roots in the past, particularly in the Venetian “machine operas” of the 17th century, as well as in the stately scores of Rameau and Gluck. But the immediate drive toward this new style of opera was instituted in Paris by Italian expatriates: Luigi Cherubini (Cherubini, Luigi), who spent the last 54 years of his life in France, and Gaspare Spontini (Spontini, Gaspare), whose most impressive operas were designed for Paris.

Cherubini was a greatly learned composer in almost all musical forms who won the admiration of Beethoven. His two most imposing operas were the ambitious Médée (1797; libretto by François-Benoît Hoffman) and a comédie lyrique, Les Deux Journées (1800; “The Two Days,” libretto by Jean-Nicolas Bouilly), which became very popular in Germany under the title Der Wasserträger (“The Water Carrier”). Spontini, in his French operas, ranged far beyond Cherubini and his other contemporaries in his demands for complex staging. Daniel-François-Esprit Auber (Auber, Daniel-François-Esprit) brought out La Muette de Portici (1828; “The Mute Girl of Portici,” also known as Masaniello, libretto by Scribe). The popularity of La Muette was phenomenal in both France and Germany. This opera remains unique in that its title character neither sings nor speaks, the role being performed by a mime. Eighteen months after the premiere of Auber's opera, the appearance of Rossini's Guillaume Tell showed that master of opera buffa and bel canto responding to the new genre. Auber's later operas include several charming comedies, among them Fra Diavolo (1830; libretto by Scribe).

The official birth of grand opera occurred in 1831, with the first French opera of another Parisian expatriate, German composer Giacomo Meyerbeer (Meyerbeer, Giacomo): Robert le diable. The popularity of this work caused a sort of frenzy (by August 1893 it had been sung 751 times at the Paris Opéra). Using an expanded, powerful orchestra, with much emphasis placed on individual instrumental colours, requiring almost every kind of singing, and filling huge stages with dazzling pageantry, four of his operas held their leading positions even through the Wagnerian revolution and into the early 20th century. Besides Robert le diable, they were Les Huguenots (1836), Le Prophète (1849), and the posthumously staged L'Africaine (1864). Scribe (Scribe, Eugène), the primary author of all of these, was the most phenomenally productive librettist of his time, writing (with the help of various collaborators) a huge number of librettos for many composers, including Auber, Boieldieu, Cherubini, Donizetti, Gounod, Halévy, Meyerbeer, Rossini, and Verdi. He was, in fact, a major force in the evolution of French grand opera.

Imitators of Meyerbeer's successes naturally sprang up immediately. Later, numerous composers who were totally unlike him stylistically—including Berlioz, Wagner, and Verdi—were influenced unwittingly by his practices. The first of the imitators was Fromental Halévy (Halévy, Fromental), whose works included at least one grand opera that could almost be mistaken for Meyerbeer's: La Juive (1835; “The Jewess,” libretto by Scribe). After the times of Meyerbeer and Halévy, grand opera began to respond to new musical and intellectual currents, evolving into a variety of mixed forms.

Like most of Berlioz (Berlioz, Hector)'s other compositions, his three operas stand apart from the mainstream of music history. When first staged at the Paris Opéra in the shadow of Robert le diable and La Dame blanche, his first opera, Benvenuto Cellini (1838; libretto by Léon de Wailly and Auguste Barbier), was a complete failure. The lighthearted Béatrice et Bénédict (his own libretto, based upon Shakespeare's Much Ado About Nothing) finally was given its premiere at Baden-Baden in 1862 by Franz Liszt. Berlioz's masterpiece, Les Troyens (his own libretto), is based on Virgil's Aeneid and divided into La Prise de Troie (“The Capture of Troy”), two acts, and Les Troyens à Carthage (“The Trojans at Carthage”), three acts. It was not performed complete during his lifetime; he heard only the second part as staged in Paris in 1863. Les Troyens is a great, noble, idiosyncratic work close in seriousness and scope to Wagner (Wagner, Richard)'s works. Berlioz's operas, like his other music, are distinguished by the individual arch of his melody, his revolutionary orchestration, and the dramatic thrust of the whole.

Even more popular than Auber as a purveyor of light operatic comedy was Jacques Offenbach (Offenbach, Jacques), a German émigré to Paris who supplied the Second Empire and the early years of the Third Republic with a long series of very tuneful, witty, and satiric works of deliberate frivolity. Remembered among them are Orphée aux enfers (1858; “Orpheus in the Underworld,” libretto by Hector Crémieux and Ludovic Halévy (Halévy, Ludovic)), La Belle Hélène (1864; “Beautiful Helen,” libretto by Henri Meilhac and Halévy), and La Vie Parisienne (1866; “Parisian Life,” libretto by Meilhac and Halévy). Left incomplete at Offenbach's death in 1880 was his major serious opera, Les Contes d'Hoffmann (The Tales of Hoffmann; libretto by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré, after their play of the same name based on tales by the German Romantic writer E.T.A. Hoffmann (Hoffmann, E.T.A.)). Recitatives replacing the original dialogue were provided by Ernst Guiraud, and the opera was staged posthumously in 1881. This fantasy involving supernatural interventions rapidly became a worldwide favourite.

German Romantic (Romanticism) opera

Romanticism—part philosophical, part literary, and part aesthetic—made one of its first appearances in opera in three works composed between 1821 and 1826 by Carl Maria von Weber (Weber, Carl Maria von). Beginning with his masterpiece, Der Freischütz (1821; “The Freeshooter,” libretto by Friedrich Kind), Weber successfully challenged the outdated “dictatorship” of Spontini at Berlin. For the Italian's stiff grandeur he substituted, in singspiel form, tender sentiment, grisly horrors, hearty choruses, moral nicety, and music of extraordinary instrumental and vocal allure. Der Freischütz illustrates the German Romantic writers' love for dark forests, the echoes of hunters' horns, the threatening supernatural, and the frustrations of pure young love. Its popularity in Germany and elsewhere was enormous.

Weber smarted under the anti-Romantic criticism of Der Freischütz as a mere singspiel (a work with spoken dialogue) rather than a musically continuous opera. His next major composition, Euryanthe (1823; libretto by Helmina von Chézy), contained no spoken dialogue. Almost since its premiere, writers have attacked the remarkable silliness (on paper) of its libretto, but most of them have never witnessed the work in performance and therefore cannot judge how the libretto works onstage with Weber's fine score. His last opera, Oberon, or The Elf King's Oath (1826; libretto, in English, by James Robinson Planché), was a return to the singspiel form. Like Euryanthe, it has not held the stage, and again the libretto has been blamed. The overtures to all three of these operas, however, remained in the symphonic repertoire.

Louis Spohr (Spohr, Louis), a violinist, conductor, and composer of instrumental music, sounds pallidly Romantic if compared with Weber, but certain of his harmonic innovations inspired Wagner, of whose early operas he was a defender. Heinrich August Marschner (Marschner, Heinrich August), more Romantic by nature than Spohr, borrowed sufficiently from Weber's style to serve as one bridge to Wagner. He displayed talent as orchestrator and melodist, and he applied his gifts to intensely Romantic and equally Teutonic librettos. The finest of his now-unheard operas is Hans Heiling (1833; libretto by Eduard Devrient (Devrient, Eduard)).

The other German-language composers of opera active during this period were less important. Albert Lortzing (Lortzing, Albert) composed several operas that have been likened to genre painting. He traveled in the direction of operetta in his popular sentimental comedies, set to his own librettos, such as Zar und Zimmermann (1837; “Tsar and Carpenter”) and Der Waffenschmied (1846; “The Armourer”). The same direction was taken by Friedrich, Freiherr von Flotow (Flotow, Friedrich, Freiherr von), whose operetta-like Martha (1847; libretto by Friedrich Wilhelm Reise) remained in the repertoire. This trend toward operetta as a less-intense variety of Romanticism continued in Die lustigen Weiber von Windsor (1849; libretto by Salomon Hermann Mosenthal, based on Shakespeare's Merry Wives of Windsor), the major success of Otto Nicolai (Nicolai, Otto), and in the extremely popular works of Franz von Suppé (Suppé, Franz von). It culminated in operetta on the highest level of musical accomplishment in the masterworks of Johann Strauss the Younger (Strauss, Johann, The Younger). Many of Strauss's operettas are known now only by their overtures and waltzes, but one of them, Die Fledermaus (1874; “The Bat,” libretto by Carl Haffner and Richard Genée), has never left the stage for long. Only the finest opéras comiques and opéras bouffes of Auber and Jacques Offenbach match Strauss's elegance, wit, humour, musical invention, and scrupulous workmanship.

Verdi (Verdi, Giuseppe)

When in 1839 an opera called Oberto, conte di San Bonifacio (libretto by Antonio Piazza, revised by Bartolomeo Merelli and Temistocle Solera) was staged at the leading Italian opera house, the Teatro alla Scala (La Scala) at Milan, its first audiences received it reasonably well. Rossini had not offered a new opera for 10 years, Bellini was dead, and Donizetti was composing for Paris, so the debut of a new talent was welcome. Those early audiences, however, could not know that Oberto had opened the active career of the greatest of all later Italian composers of opera, Giuseppe Verdi (Verdi, Giuseppe). His third opera, Nabucodonosor, known as Nabucco (1842; libretto by Solera), displayed the emergence of a musical dramatist of enormous vigour and rich melodic invention.

Verdi long suffered from his inability to obtain librettos worthy of his special talents, but each of the six operas that he wrote between Nabucco and Macbeth (1847) includes scenes and numbers of great power and immediately winning, memorable melody. Even Macbeth (libretto by Francesco Maria Piave, revised in 1865 by Verdi to a libretto in French), although it is marked both dramatically and musically by passages of astonishing vitality, has structural weaknesses. (For further discussion of Verdi's Macbeth and other operas based on Shakespeare's plays, see Sidebar: Shakespeare and Opera.)

Of his five operas written between 1847 and 1851, the most noteworthy is Luisa Miller (1849; libretto by Salvatore Cammarano). During this period Verdi was on the way to becoming a public symbol of the Risorgimento, the Italian movement of rebellion against foreign domination and toward political unification, both because of the patriotic emphasis in several of his librettos and because of his staunchly liberal public character (he was eventually to become a true national hero).

Beginning in 1851, Verdi produced three of his greatest works, having found librettos that fired his imagination. The first of them was Rigoletto (libretto by Piave), in which his abundant creation of melody was at the service of his gift for musical characterization. Less than two years later came Il trovatore (1853; “The Troubadour,” libretto by Cammarano), perhaps unmatched among Verdi's operas for its profusion of strong and memorable melodies. Very soon thereafter, La traviata (1853; libretto by Piave, after fils (Dumas, Alexandre, fils)'s La Dame aux camélias, “Lady of the Camellias”) had its first performance. Although the opera was at first a failure, it later came to be accepted as a masterpiece. It also established a composer's right to set librettos dealing with contemporary life. By comparison with Il trovatore, with its thunderous melodrama, La traviata seems an intimate, quiet, almost chamber-music opera. The musical portrait of Violetta, the tubercular courtesan heroine, is extraordinary for its depiction of the effects of love and sorrow on her character.

Verdi composed steadily over the following years, and nearly all of his works have remained in the repertoire. In 1867, for Paris, to a libretto in French, he wrote Don Carlos (libretto by François-Joseph Méry and Camille du Locle, revised by Verdi in 1884 to an Italian translation and again in 1887). This long opera, particularly its fourth act, is majestic and subtle, its various musical confrontations—many of them duets—displaying a depth of characterization hitherto unknown in Italian or French opera.

By 1869 Verdi's fame had become so international that the khedive of Egypt invited him to compose an opera for Cairo to mark the opening of the new Cairo Opera House (and possibly the opening of the Suez Canal). In fact, the canal began to operate in 1869, but the opera received its premiere at Cairo only in 1871. This was Aida (libretto by Antonio Ghislanzoni, based on a scenario by Auguste Mariette (Mariette, Auguste), the French Egyptologist, and Camille du Locle, with the collaboration of Verdi). The masterly libretto and its four well-delineated principal characters evoked from Verdi a Meyerbeerian opera of such unfailing melodic, orchestral, and dramatic richness that many have called Aida his finest work. For pageantry, combined as it is with harmonic, melodic, and instrumental skills and convincing, if generalized, characterization, it remains unrivaled.

By 1869 Verdi's fame had become so international that the khedive of Egypt invited him to compose an opera for Cairo to mark the opening of the new Cairo Opera House (and possibly the opening of the Suez Canal). In fact, the canal began to operate in 1869, but the opera received its premiere at Cairo only in 1871. This was Aida (libretto by Antonio Ghislanzoni, based on a scenario by Auguste Mariette (Mariette, Auguste), the French Egyptologist, and Camille du Locle, with the collaboration of Verdi). The masterly libretto and its four well-delineated principal characters evoked from Verdi a Meyerbeerian opera of such unfailing melodic, orchestral, and dramatic richness that many have called Aida his finest work. For pageantry, combined as it is with harmonic, melodic, and instrumental skills and convincing, if generalized, characterization, it remains unrivaled.In 1869 the public and the writers on opera assumed that Verdi would continue to produce a new opera every few years. But 16 elapsed before the premiere of his next opera, Otello (1887; libretto by Arrigo Boito (Boito, Arrigo)). Verdi's varied, intensely dynamic, compressed, and tragic score was the result not only of his ripened genius but also of nearly 50 years of operatic practice. Many critics consider it the finest tragic opera ever composed.

In the following six years, rumours grew that the aged Verdi not only was composing still another opera but that it was to be a comedy. The comic masterpiece Falstaff (libretto by Boito, derived largely from Shakespeare's Merry Wives of Windsor and Henry IV) was performed in 1893. An opera buffa with serious overtones, Falstaff always has been praised by critics and enthusiasts, but it has never become a true popular favourite.

Arrigo Boito (Boito, Arrigo) not only wrote the librettos of Verdi's last two operas but was himself a composer, as well as a poet, polemicist, and man of letters. He completed only one opera, Mefistofele (1868; his own libretto, derived from Goethe (Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von)'s Faust). It was at first a failure but eventually became more popular.

Wagner (Wagner, Richard) and his successors

Richard Wagner is a unique composer in the history of both opera and music in general. A larger-than-life figure with a powerful, tenacious, and at times stubbornly confused intellect, he wrote both the music and the librettos of his operas. He began his career, except for a youthful attempt, with two grand operas mixing the influences of Meyerbeer, Marschner, and Weber: Das Liebesverbot (1836; “The Ban on Love”) and Rienzi (1842). In 1843, with Der fliegende Holländer (The Flying Dutchman), he began to develop what was to become an extremely personal, powerful manner of operatic construction. Turning to mythic legend for his subjects and with an unacknowledged debt to the operas of Weber and Marschner, while dispensing with the trappings of grand opera, he composed an intensely German, Romantic opera. In it he instituted the use of brief melodic and other motifs as materials for evolving a more or less continuous web of music in which the separate numbers of earlier opera appeared only when the libretto demanded them. Already, at age 30, he was giving harmony, in very unclassical guise, a central constructive role in the creation of both drama and characterization.

Patiently and challengingly elaborating a vast, interlocked system of theories in many published books and essays, Wagner continued the ripening of his style in two large, transitional operas, Tannhäuser (1845) and Lohengrin (1850). Tannhäuser again displays some grand-opera characteristics (particularly in the revision of it that Wagner prepared for the 1861 Paris performance); Lohengrin, the last of Wagner's serious operas peopled by human beings of recognizable dimensions, has been called the Romantic opera par excellence.

The earliest example of what Wagner called music drama (a term he preferred to opera) was the monumental Tristan und Isolde (1857–59; first performed 1865), the libretto of which illustrates his obsession with the idea of man's redemption through woman's love. Tristan und Isolde advances harmonic language. The score is woven in a harmonic idiom so advanced chromatically that it speeded the destruction of orthodox concepts of harmony. Tristan requires singers possessed of powerful voices capable of penetrating a vastly enlarged orchestra. It came to be regarded as the greatest German opera of the late 19th century, and its influence upon compositional methods and techniques continued into the 20th century.