Baltic Sea

sea, Europe

Introduction

German Ostsee, Swedish Östersjön, Russian Baltiyskoye More, Finnish Itämeri, Polish Morze Bałtyckie

arm of the North Atlantic Ocean, extending northward from the latitude of southern Denmark almost to the Arctic Circle and separating the Scandinavian Peninsula from the rest of continental Europe. The largest expanse of brackish water in the world, the semienclosed and relatively shallow Baltic Sea is of great interest to scientists, while to historians it represents the economic core of the Hanseatic League, the great medieval trading group of northern European ports. The many names for the sea attest to its strategic position as a meeting place of many countries.

arm of the North Atlantic Ocean, extending northward from the latitude of southern Denmark almost to the Arctic Circle and separating the Scandinavian Peninsula from the rest of continental Europe. The largest expanse of brackish water in the world, the semienclosed and relatively shallow Baltic Sea is of great interest to scientists, while to historians it represents the economic core of the Hanseatic League, the great medieval trading group of northern European ports. The many names for the sea attest to its strategic position as a meeting place of many countries.The Baltic Sea covers about 149,000 square miles (386,000 square km). The catchment area drained by the rivers bringing fresh water into the Baltic is about four times as large as the sea itself. The Baltic proper stretches southwest-northeast on the eastern side of the Scandinavian Peninsula from latitude 54° N to very near the Arctic Circle; its major axis, from eastern Denmark to southern Finland, is a little more than 1,000 miles (1,600 km) long, with an average width of about 120 miles (190 km). The western Baltic extends north through insular Denmark and includes the Kattegat, a strait separating peninsular Denmark ( Jutland, or Jylland) from southwestern Sweden. The Kattegat is bounded on the north by the Skagerrak, a deep inlet of the North Sea that separates southern Norway from northern Jutland.

The large islands of Bornholm (Denmark) and Öland and Gotland (Sweden) lie in the western Baltic, while the Åland Islands (Finnish: Ahvenanmaa), farther north, rise from a narrows between Sweden and Finland and mark the entrance to the arm of the Baltic known as the Gulf of Bothnia (Bothnia, Gulf of). Just to the south of the Åland Islands, the narrow Gulf of Finland (Finland, Gulf of) stretches eastward between Finland to the north, Estonia to the south, and Russia around the eastern end, with St. Petersburg at its head. Proceeding clockwise from the west, the countries bounding the Baltic are Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Russia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Germany.

The large islands of Bornholm (Denmark) and Öland and Gotland (Sweden) lie in the western Baltic, while the Åland Islands (Finnish: Ahvenanmaa), farther north, rise from a narrows between Sweden and Finland and mark the entrance to the arm of the Baltic known as the Gulf of Bothnia (Bothnia, Gulf of). Just to the south of the Åland Islands, the narrow Gulf of Finland (Finland, Gulf of) stretches eastward between Finland to the north, Estonia to the south, and Russia around the eastern end, with St. Petersburg at its head. Proceeding clockwise from the west, the countries bounding the Baltic are Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Russia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Germany.Physical features

Physiography

The Baltic Sea is a shrunken remnant of the water-covered region that emerged as the melting Scandinavian ice sheet retreated toward the Arctic at the end of the Pleistocene Epoch glaciations. Some 14,000 years ago, ice covered all of northern Europe as far south as the present German-Polish coastline; by 7700 BC glacial meltwater had formed the Yoldia Sea, which stretched east from the present Skagerrak across what is now lake-strewn southern Sweden as far as the present Lake Ladoga (Ladoga, Lake), beyond the bend of the Gulf of Finland. A thousand years later, only limited areas of stagnant ice remained in northern Sweden, leaving the freshwater Ancylus Lake stretching from Arctic Sweden and Finland to the present southern Baltic. Later changes, about 4500 BC, led to a breach of the land bridge between the present Baltic and North seas and to fragmentation of the Jutland peninsula by The Sound (Sound, The) (Øresund), the Store Strait (Great Belt) (Storebælt), and the Lille Strait (Little Belt) (Lillebælt). Many of the lowland regions surrounding the sea have been rebounding slowly since the great weight of the glaciers was removed; however, in places such as Stockholm, rising sea levels have slightly exceeded the rate of land uplift. Land uplift and deposition are building up the head of the almost tideless Gulf of Bothnia.

The Baltic Sea is a shrunken remnant of the water-covered region that emerged as the melting Scandinavian ice sheet retreated toward the Arctic at the end of the Pleistocene Epoch glaciations. Some 14,000 years ago, ice covered all of northern Europe as far south as the present German-Polish coastline; by 7700 BC glacial meltwater had formed the Yoldia Sea, which stretched east from the present Skagerrak across what is now lake-strewn southern Sweden as far as the present Lake Ladoga (Ladoga, Lake), beyond the bend of the Gulf of Finland. A thousand years later, only limited areas of stagnant ice remained in northern Sweden, leaving the freshwater Ancylus Lake stretching from Arctic Sweden and Finland to the present southern Baltic. Later changes, about 4500 BC, led to a breach of the land bridge between the present Baltic and North seas and to fragmentation of the Jutland peninsula by The Sound (Sound, The) (Øresund), the Store Strait (Great Belt) (Storebælt), and the Lille Strait (Little Belt) (Lillebælt). Many of the lowland regions surrounding the sea have been rebounding slowly since the great weight of the glaciers was removed; however, in places such as Stockholm, rising sea levels have slightly exceeded the rate of land uplift. Land uplift and deposition are building up the head of the almost tideless Gulf of Bothnia. The shallowest part of the Baltic is the continental shelf, from which rise the islands of the Danish archipelago. There the Lille Strait divides eastern Jutland from the island of Funen (Fyn), which is itself separated from Zealand (Sjælland) by the deeper Store Strait. The narrow channel of The Sound between Denmark and Sweden restricts ships to drafts up to 41 feet (12.5 metres); larger vessels call at Göteborg, Swed., which is the biggest oil port in the Baltic.

The shallowest part of the Baltic is the continental shelf, from which rise the islands of the Danish archipelago. There the Lille Strait divides eastern Jutland from the island of Funen (Fyn), which is itself separated from Zealand (Sjælland) by the deeper Store Strait. The narrow channel of The Sound between Denmark and Sweden restricts ships to drafts up to 41 feet (12.5 metres); larger vessels call at Göteborg, Swed., which is the biggest oil port in the Baltic.The greatest deeps in the Baltic lie off the southeast coast of Sweden between Nyköping and the island of Gotland, where a depth of 1,506 feet (459 metres) is reached in Landsort Deep; between Gotland and Latvia in Gotland Deep (817 feet 【249 metres】); and also in the Gulf of Bothnia in the Åland Sea between Sweden and the Åland Islands. A deepwater channel also extends along most of the Gulf of Finland. The Baltic Sea proper contains a series of basins (e.g., in the Gulf of Gdańsk) divided by shallow shelves.

Climate

Marked seasonality is the principal feature of the Baltic climate. Winters are long and cold, and summers are short and comparatively warm. Mean temperatures (temperature) range from about 14 °F (− 10 °C) over the Gulfs of Bothnia and Finland in midwinter to about 63 °F (17 °C) over southern parts of the Baltic in midsummer. Variability is another facet of the climate. Mild maritime weather from the North Atlantic sometimes extends to the Baltic. At other times, continental influences are predominant, giving periods of severe cold in winter and warm, dry weather in summer. Precipitation varies with weather type, averaging 20 to 24 inches (about 500 to 600 mm) per year. Cloudy weather predominates, and fog is most frequent in spring and early summer. Winds tend to be variable and do not usually reach gale force. Sea breezes commonly occur over coastal regions in summer.

Hydrology

The Baltic Sea is so nearly landlocked (and its outlet so shallow) that its waters are remarkably fresh. Its longest rivers, the Vistula (Vistula River) and the Oder (Oder River), drain regions that have a temperate continental climate; they have low evaporation rates and become swollen by spring snowmelt, thus further reducing the salinity of the Baltic. The highest salinity is recorded in the western Baltic, where it is about 10 parts per thousand at the surface and about 15 parts per thousand near the bottom; the lowest is at the head of the Gulf of Bothnia, where it is less than a third of this amount. The low salinity and the shallow coastal waters cause pack ice to accumulate at the head of the Gulf of Bothnia and off Finland in most winters; sometimes the ice becomes banked up in pressure ridges that are almost 50 feet (15 metres) high. Drift ice forms at and north of the Åland Islands area and also in the inner reaches of the Gulf of Finland, reaching a depth of about 3 feet (1 metre). Navigation between Stockholm and Turku and Helsinki in Finland is possible, except in the most severe winters. Along the Polish and German coasts, ports can be closed by ice for several days a year. In summer the surface waters remain cool, but Arctic temperatures persist at lower depths.

The Baltic, sheltered from the strong North Sea tides, is remarkable for the general absence of tidal currents. Although the great influx of river water and surface runoff, including spring snowmelt, causes an outflow of surface water into the North Sea, a deeper countercurrent of denser salt water flows into the Baltic. Strong northeasterly winds may cause high waves along the southern shores, resulting in coastal flooding; conversely, southwesterly winds have contributed to the formation of sand dunes along the German and Polish coasts and also cause an accumulation of water in the northern Baltic.

Coastal features

The coasts of Sweden and Finland are highly fretted and generally rocky, whereas those of the southern Baltic are flat and rather featureless. Where the crystalline rocks of the ancient rock mass of the Baltic Shield outcrop along the northern coasts, partly obscured by glacial drift and marine deposits, they are often fringed by the low, rocky islands known as a skerry guard. These are most numerous in the Saltsjön (Salt Bay) between Stockholm and the open waters of the Gulf of Bothnia and off the southwest coast of Finland. Off southeastern Sweden the narrow, elongated islands of Öland and Gotland consist of ancient limestone partly covered by sandy drift deposits. The rectangular island of Bornholm off southern Sweden was formed from a detached fragment of granite, and its high cliffs were shaped by faulting and shearing of the rock strata.

The coasts of Sweden and Finland are highly fretted and generally rocky, whereas those of the southern Baltic are flat and rather featureless. Where the crystalline rocks of the ancient rock mass of the Baltic Shield outcrop along the northern coasts, partly obscured by glacial drift and marine deposits, they are often fringed by the low, rocky islands known as a skerry guard. These are most numerous in the Saltsjön (Salt Bay) between Stockholm and the open waters of the Gulf of Bothnia and off the southwest coast of Finland. Off southeastern Sweden the narrow, elongated islands of Öland and Gotland consist of ancient limestone partly covered by sandy drift deposits. The rectangular island of Bornholm off southern Sweden was formed from a detached fragment of granite, and its high cliffs were shaped by faulting and shearing of the rock strata.The coastal features of eastern Denmark are the outcome of Pleistocene glaciation and of subsequent changes in sea level. The east coast of Jutland, north of the Djursland peninsula, is smooth and low-lying. To the south are shallow bays divided by low promontories. In the area around Schleswig, shallow straight-sided fjords (fjord) (Förden) occur, and the Flensborg Fjord (Flensburger Förde) forms part of the boundary between Denmark and Germany. The islands of the Danish archipelago have a broken coastline, with a number of shallow inlets and also bars, notably the Odense bar on the island of Funen. Where terminal moraines (moraine) (deposits marking the farthest extent of glaciers) reach the sea, low promontories are formed. Solid rock seldom outcrops, except for the moderate-sized chalk cliffs along the eastern coast of the island of Møn.

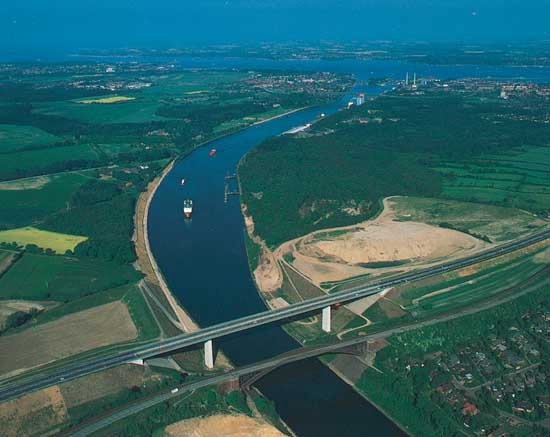

The Baltic coastline of western Germany is one of shallow fjords and bays. Kiel lies at the head of one such inlet, south of the entrance to the Kiel (Baltic–North Sea) Canal (Kiel Canal), which runs through German territorial waters. To the east is the Bay of Lübeck at the head of the Trave River estuary, where Travemünde—a ferry port for Copenhagen and Sweden—combines the functions of a seaport and tourist resort. Farther to the east, the German coast of Mecklenburg–West Pomerania is flat and low-lying. A series of long shingle bars (Nehrungen), capped by moving sand dunes, has been built up there, cutting off the distinctive shallow lagoons (lagoon) (Haffs) from the open sea. Examples are the west-east spit of Darsser-Ort, on the island of Rügen, and the link (near Świnoujście, Pol.) between the islands of Usedom (Germany) and Wolin ( Poland), which isolate Szczeciński Lagoon from the open sea. East of the Polish frontier, the port of Szczecin lies at the mouth of the Oder River. Solid rock outcrops conspicuously only on the island of Rügen, where the remarkably irregular coastline includes chalk cliffs that reach a height of about 400 feet (120 metres).

The Baltic coastline of western Germany is one of shallow fjords and bays. Kiel lies at the head of one such inlet, south of the entrance to the Kiel (Baltic–North Sea) Canal (Kiel Canal), which runs through German territorial waters. To the east is the Bay of Lübeck at the head of the Trave River estuary, where Travemünde—a ferry port for Copenhagen and Sweden—combines the functions of a seaport and tourist resort. Farther to the east, the German coast of Mecklenburg–West Pomerania is flat and low-lying. A series of long shingle bars (Nehrungen), capped by moving sand dunes, has been built up there, cutting off the distinctive shallow lagoons (lagoon) (Haffs) from the open sea. Examples are the west-east spit of Darsser-Ort, on the island of Rügen, and the link (near Świnoujście, Pol.) between the islands of Usedom (Germany) and Wolin ( Poland), which isolate Szczeciński Lagoon from the open sea. East of the Polish frontier, the port of Szczecin lies at the mouth of the Oder River. Solid rock outcrops conspicuously only on the island of Rügen, where the remarkably irregular coastline includes chalk cliffs that reach a height of about 400 feet (120 metres). East of Szczecin the coast of Pomerania (Pomorze) is generally flat and featureless, with sand dunes and spits bounding brackish lagoons. The Vistula River drains into the Baltic through a number of distributaries; the historic city of Gdańsk lies on the most westerly of these, the Motława. To the east, spectacular lagoon and shingle bar features have developed. Sand dunes, covering an elongated shingle spit, almost enclose the brackish Wiślany (Frisches) Lagoon, at the northeastern end of which lies Königsberg, the historic German outpost founded by the Teutonic Knights. Once the chief city and port of East Prussia, it is now the Russian port of Kaliningrad. Northward, the cliff coast is noted for its amber, a fossilized resin that formed a valued item of medieval trade throughout the Baltic and as far afield as Venice, which was reached by the “Amber Route” via Kraków (Pol.) and Vienna. At the northern end of the triangular inlet of the Curonian Lagoon, at the mouth of the Neman River, lies Klaipėda, Lith., the most northeasterly city of Germanic origin in the Baltic. Cutting off the lagoon from the Baltic is another shingle spit (the Curonian Spit), some 60 miles (100 km) long, capped by low fixed dunes and fringed by high moving dunes of white sand.

East of Szczecin the coast of Pomerania (Pomorze) is generally flat and featureless, with sand dunes and spits bounding brackish lagoons. The Vistula River drains into the Baltic through a number of distributaries; the historic city of Gdańsk lies on the most westerly of these, the Motława. To the east, spectacular lagoon and shingle bar features have developed. Sand dunes, covering an elongated shingle spit, almost enclose the brackish Wiślany (Frisches) Lagoon, at the northeastern end of which lies Königsberg, the historic German outpost founded by the Teutonic Knights. Once the chief city and port of East Prussia, it is now the Russian port of Kaliningrad. Northward, the cliff coast is noted for its amber, a fossilized resin that formed a valued item of medieval trade throughout the Baltic and as far afield as Venice, which was reached by the “Amber Route” via Kraków (Pol.) and Vienna. At the northern end of the triangular inlet of the Curonian Lagoon, at the mouth of the Neman River, lies Klaipėda, Lith., the most northeasterly city of Germanic origin in the Baltic. Cutting off the lagoon from the Baltic is another shingle spit (the Curonian Spit), some 60 miles (100 km) long, capped by low fixed dunes and fringed by high moving dunes of white sand.In the eastern Baltic, glacial deposits cover solid rock, and the coast is broken by broad bars, such as those on which the Latvian port of Riga lies. At the head of the Gulf of Finland is the city of St. Petersburg (Saint Petersburg), founded by Peter I (the Great) as Russia's “window on Europe,” with its white buildings in classical style lining the waterfront of the Neva River.

Economic aspects

The Baltic Sea is no longer the major highway of trade (international trade) that it was in the Middle Ages, when it flourished as the main means of communication between the ports (Lübeck, Rostock, Visby, and Gdańsk) of the Hanseatic League. The German Hansa merchants traded mainly in fish, notably salted herring and stockfish (dried cod from Norway and Iceland), and also in softwood timber for shipbuilding, hemp for ropes, flax for sailcloth, and grain. Forest products included honey and furs, notably from Russia and Finland, as well as Stockholm tar and amber, the latter being a semiprecious commodity. Overfishing of herring, the opening up of trade to the Americas and the Caribbean following the European Age of Discovery (mid-15th to mid-16th century), and the increase in the size of sailing ships led to the decline of the Hanseatic League. Copenhagen, however, continued to prosper on the profits from tolls exacted from passing shipping, until tolls were abolished in 1857.

The Baltic Sea is no longer the major highway of trade (international trade) that it was in the Middle Ages, when it flourished as the main means of communication between the ports (Lübeck, Rostock, Visby, and Gdańsk) of the Hanseatic League. The German Hansa merchants traded mainly in fish, notably salted herring and stockfish (dried cod from Norway and Iceland), and also in softwood timber for shipbuilding, hemp for ropes, flax for sailcloth, and grain. Forest products included honey and furs, notably from Russia and Finland, as well as Stockholm tar and amber, the latter being a semiprecious commodity. Overfishing of herring, the opening up of trade to the Americas and the Caribbean following the European Age of Discovery (mid-15th to mid-16th century), and the increase in the size of sailing ships led to the decline of the Hanseatic League. Copenhagen, however, continued to prosper on the profits from tolls exacted from passing shipping, until tolls were abolished in 1857. The construction of the Kiel Canal in the late 19th century and the development of railways and highways in the 20th century began to change the nature of trade and transport across the Baltic Sea. World War II also brought political and economic change to the region, and traditional trading patterns were amended accordingly. In the 21st century the number of ocean vessels sailing around Jutland is only a fraction of that of earlier decades. Instead, there has been an increase in Baltic Sea crossings by large roll-on, roll-off ferries and fast hovercraft, hydrofoils, and catamarans. There are many such linkages, the busiest being between Helsingør, Den., and Helsingborg, Swed.

The construction of the Kiel Canal in the late 19th century and the development of railways and highways in the 20th century began to change the nature of trade and transport across the Baltic Sea. World War II also brought political and economic change to the region, and traditional trading patterns were amended accordingly. In the 21st century the number of ocean vessels sailing around Jutland is only a fraction of that of earlier decades. Instead, there has been an increase in Baltic Sea crossings by large roll-on, roll-off ferries and fast hovercraft, hydrofoils, and catamarans. There are many such linkages, the busiest being between Helsingør, Den., and Helsingborg, Swed. Bulk cargoes of oil and coal still come by all water routes into the Baltic, and many exports of minerals, timber, and wood products move in the opposite direction by sea around Jutland. These traditional exports represent a diminishing value in overall trade. The greatest values are in consumer goods, most of which are carried in containers by integrated land and sea transport to markets and to and from the North Sea ports of Hamburg, Ger., and Rotterdam, Neth. This has led to increased interest in building a bridge between Denmark and Sweden. Shipbuilding has declined in Sweden but has continued in Poland and Finland (especially for ice-strengthened vessels); marine engines are produced in Denmark. Generally, however, light engineering, high-quality furniture production, and motor-vehicle manufacturing have replaced many of these maritime-based industries.

Bulk cargoes of oil and coal still come by all water routes into the Baltic, and many exports of minerals, timber, and wood products move in the opposite direction by sea around Jutland. These traditional exports represent a diminishing value in overall trade. The greatest values are in consumer goods, most of which are carried in containers by integrated land and sea transport to markets and to and from the North Sea ports of Hamburg, Ger., and Rotterdam, Neth. This has led to increased interest in building a bridge between Denmark and Sweden. Shipbuilding has declined in Sweden but has continued in Poland and Finland (especially for ice-strengthened vessels); marine engines are produced in Denmark. Generally, however, light engineering, high-quality furniture production, and motor-vehicle manufacturing have replaced many of these maritime-based industries.Fishing (commercial fishing) in the Baltic is less important than in the past. Most of the catch consists of herring, cod, and sprats followed by smaller quantities of eel, salmon, and shellfish. The Baltic has been divided into national zones for fishing, with the bulk of the catch coming from the southern sector and from the Kattegat. Similarly, the seabed has been divided among the Baltic countries, and exploration for hydrocarbons has taken place especially off the eastern shore.

Study and exploration (European exploration)

The Vikings (Viking) began opening the Baltic to trade in the 8th century AD, and since then the historic events of the region have been related to attempts at controlling the sea. Swedish expansion from the 12th to the 17th century relied on shipbuilding and sea power, and the basis of the Danish empire was its ability to command the straits through the Danish archipelago. The prosperity of the Hanseatic League arose when German Baltic ports provided alternative trade gateways to the Danish straits.

The intensity of the use of the Baltic for seafaring has been matched by equally intensive scientific research. The sea's hydrologic and chemical properties were among the first to be studied systematically. Because of its status as a semienclosed sea—with stratified water columns, low water temperatures, a slow circulation pattern, and much runoff from coastal and river areas with high concentrations of population and industry—the Baltic has been recognized as ecologically vulnerable. The focus of much research has been on monitoring such pollution indicators as oxygen depletion in the deep basins and the concentration of harmful substances in aquatic birdlife. Threats to unique regional flora and fauna have led to cooperation among Baltic countries on environmental protection.

As early as the 1950s, environmental scientists in the Baltic region became aware of environmental degradation resulting from large-scale industrial development and chemical runoffs from agriculture. This awareness led to the 1974 signing by Baltic countries of the Helsinki Convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea Area, an agreement that was put into effect in 1980, revised in 1992, and reimplemented in 2000. The Helsinki Convention was one of the first international attempts to control land-based sources of pollution in a shared marine environment. Although some significant improvements in pollution control have been achieved, particularly in the Scandinavian countries, it is difficult to determine how much these improvements can be attributed to the institutions established under the Helsinki Convention.

Ed.

Additional Reading

Aarno Voipio (ed.), The Baltic Sea (1981), is an informative overview of the area. Boris Winterhalter (ed.), The Baltic Sea (1988), is a set of colloquium papers on the Baltic's geology; and Ole Bagge and Otto Rechlin, Baltic Sea Fishery Resources (1989), is a collection of the proceedings from a symposium. A special issue of Ambio, vol. 9, no. 3–4 (1980), is devoted to the Baltic. Gunnar Alexandersson, The Baltic Straits (1982), discusses The Sound, Kattegat, and Skagerrak. General references include Ing-Marie Gren, R. Kerry Turner, and Fredrik Wulff, Managing a Sea: The Ecological Economics of the Baltic (2000). References on the environmental status and condition of the Baltic that include overviews of deliberations and studies are the Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission, The Third Baltic Sea Pollution Load Compilation (PLC 3) (1998), The Baltic Sea Joint Comprehensive Environment Action Programme: Recommendations for Updating and Strengthening (1998), Third Periodic Assessment of the State of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea, 1989–1993, 2 vol. (1996), and Activities Overview (annual). A dissertation completed at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences characterizes an economic approach to the reduction of nutrient pollution in the Baltic: Katarina Elofsson, Cost Effective Reductions in the Agricultural Load of Nitrogen to the Baltic Sea (1997). A review of the international agreements relating to marine pollution control in the Baltic and other regional seas can be found in James M. Broadus et al., Comparative Assessment of Regional International Programs to Control Land-Based Marine Pollution: The Baltic, North Sea, and Mediterranean (1993). Ed.

- Approximate chemical composition of a typical mammalian cell

- Approximate Composition of Portland Cement, Table

- Approximate energy expenditure for activity levels

- Approximate Strengths of Selected Regular Armed Forces of the Wolrd

- Approximate Strengths of Selected Regular Armed Forces of the World

- Approximate Strengths of Selected Regular Armed Forces of the World 1

- Approximate Strengths of Selected Regular Armed Forces of the World 2

- Apra Harbor

- apraxia

- Aprey faience

- apricot

- Apries

- April

- April Fools' Day

- April Theses

- a priori knowledge

- apse

- apterygote

- Aptheker, Herbert

- Aptian Stage

- aptitude test

- aptronym

- Apuleius, Lucius

- Apure

- Apure River