space exploration

Introduction

the investigation, by means of manned and unmanned spacecraft, of the reaches of the universe beyond Earth's atmosphere and the use of the information so gained to increase knowledge of the cosmos and benefit humanity.

the investigation, by means of manned and unmanned spacecraft, of the reaches of the universe beyond Earth's atmosphere and the use of the information so gained to increase knowledge of the cosmos and benefit humanity. Humans have always looked at the heavens and wondered about the nature of the objects seen in the night sky. With the development of rockets and the advances in electronics and other technologies in the 20th century, it became possible to send machines and animals and then people above Earth's atmosphere into outer space. Well before technology made these achievements possible, however, space exploration had already captured the minds of many people, not only aircraft pilots and scientists but also writers and artists. The strong hold that space travel has always had on the imagination may well explain why professional astronauts and laypeople alike consent at their great peril, in the words of Tom Wolfe (Wolfe, Tom) in the The Right Stuff (1979), to sit “on top of an enormous Roman candle, such as a Redstone, Atlas, Titan or Saturn rocket, and wait for someone to light the fuse.” It perhaps also explains why space exploration has been a common and enduring theme in literature and art. As centuries of speculative fiction in books and more recently in films make clear, “one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind” was taken by the human spirit many times and in many ways before Neil Armstrong (Armstrong, Neil) stamped humankind's first footprint on the Moon.

Humans have always looked at the heavens and wondered about the nature of the objects seen in the night sky. With the development of rockets and the advances in electronics and other technologies in the 20th century, it became possible to send machines and animals and then people above Earth's atmosphere into outer space. Well before technology made these achievements possible, however, space exploration had already captured the minds of many people, not only aircraft pilots and scientists but also writers and artists. The strong hold that space travel has always had on the imagination may well explain why professional astronauts and laypeople alike consent at their great peril, in the words of Tom Wolfe (Wolfe, Tom) in the The Right Stuff (1979), to sit “on top of an enormous Roman candle, such as a Redstone, Atlas, Titan or Saturn rocket, and wait for someone to light the fuse.” It perhaps also explains why space exploration has been a common and enduring theme in literature and art. As centuries of speculative fiction in books and more recently in films make clear, “one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind” was taken by the human spirit many times and in many ways before Neil Armstrong (Armstrong, Neil) stamped humankind's first footprint on the Moon.Achieving spaceflight enabled humans to begin to explore the solar system and the rest of the universe, to understand the many objects and phenomena that are better observed from a space perspective, and to use for human benefit the resources and attributes of the space environment. All of these activities—discovery, scientific understanding, and the application of that understanding to serve human purposes—are elements of space exploration. (For a general discussion of spacecraft, launch considerations, flight trajectories, and navigation, docking, and recovery procedures, see spaceflight.)

Overview of recent space achievements

Motivations for space activity

Although the possibility of exploring space has long excited people in many walks of life, for most of the latter 20th century only national governments could afford the very high costs of launching people and machines into space. This reality meant that space exploration had to serve very broad interests, and it indeed has done so in a variety of ways. Government space programs have increased knowledge, served as indicators of national prestige and power, enhanced national security and military strength, and provided significant benefits to the general public. In areas where the private sector could profit from activities in space, most notably the use of satellites as telecommunication relays, commercial space activity has flourished without government funding.

In the years after World War II, governments assumed a leading role in the support of research that increased fundamental knowledge about nature, a role that earlier had been played by universities, private foundations, and other nongovernmental supporters. This change came for two reasons. First, the need for complex equipment to carry out many scientific experiments and for the large teams of researchers to use that equipment led to costs that only governments could afford. Second, governments were willing to take on this responsibility because of the belief that fundamental research would produce new knowledge essential to the health, security, and quality of life of their citizens. Thus, when scientists sought government support for early space experiments, it was forthcoming. Since the start of space efforts in the United States, the Soviet Union, and Europe, national governments have given high priority to the support of science done in and from space. From modest beginnings, space exploration has expanded under government support to include multibillion-dollar exploratory missions in the solar system and to major space-based astronomical observatories such as the Hubble Space Telescope.

Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev (Khrushchev, Nikita Sergeyevich) in 1957 used the fact that his country had been first to launch a satellite as evidence of the technological power of the Soviet Union and of the superiority of communism. He repeated these claims after Yury Gagarin (Gagarin, Yury Alekseyevich)'s orbital flight in 1961. Although U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower (Eisenhower, Dwight D.) had decided not to compete for prestige with the Soviet Union in a space race, his successor, John F. Kennedy (Kennedy, John F.), had a different view. On April 20, 1961, in the aftermath of the Gagarin flight, he asked his advisers to identify a “space program which promises dramatic results in which we could win.” The response came in a May 8, 1961, memorandum recommending that the United States commit to sending people to the Moon, because “dramatic achievements in space…symbolize the technological power and organizing capacity of a nation” and because the ensuing prestige would be “part of the battle along the fluid front of the cold war.” From 1961 until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, competition between the United States and the Soviet Union was a major influence on the pace and content of their space programs. Other countries also viewed having a successful space program as an important indicator of national strength.

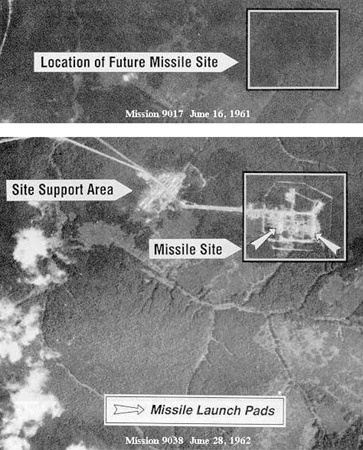

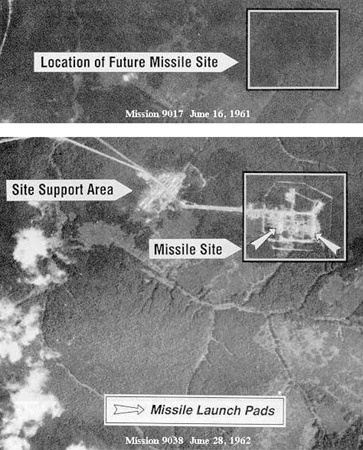

Even before the first satellite was launched, U.S. leaders recognized that the ability to observe military activities around the world from space would be an asset to national security. Following on the success of its photoreconnaissance satellites, which began operation in 1960, the United States built increasingly complex observation and electronic-intercept intelligence satellites. The Soviet Union also quickly developed an array of intelligence satellites, and later a few other countries instituted their own satellite observation programs. Intelligence-gathering satellites have been used to verify arms-control agreements, provide warnings of military threats, and identify targets during military operations, among other uses.

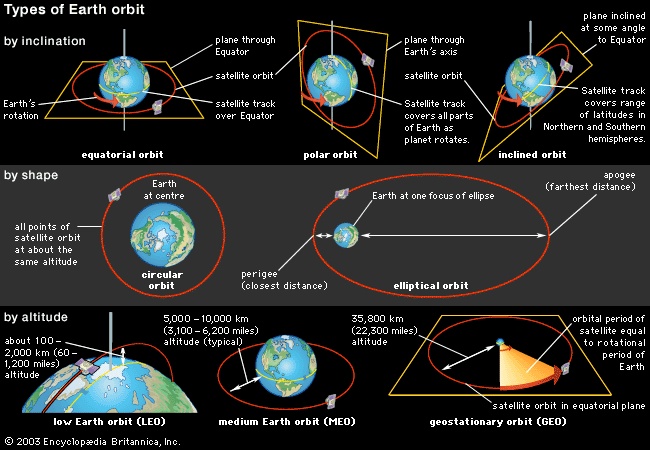

Even before the first satellite was launched, U.S. leaders recognized that the ability to observe military activities around the world from space would be an asset to national security. Following on the success of its photoreconnaissance satellites, which began operation in 1960, the United States built increasingly complex observation and electronic-intercept intelligence satellites. The Soviet Union also quickly developed an array of intelligence satellites, and later a few other countries instituted their own satellite observation programs. Intelligence-gathering satellites have been used to verify arms-control agreements, provide warnings of military threats, and identify targets during military operations, among other uses.In addition to providing security benefits, satellites offered military forces the potential for improved communications, weather observation, navigation, and position location. This led to significant government funding for military space programs in the United States and the Soviet Union. Although the advantages and disadvantages of stationing force-delivery weapons in space have been debated, as of the early 21st century, such weapons have not been deployed, nor have space-based antisatellite systems—that is, systems that can attack or interfere with orbiting satellites. The stationing of weapons of mass destruction in orbit or on celestial bodies is prohibited by international law.

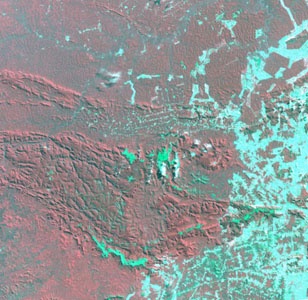

Governments realized early on that the ability to observe Earth from space could provide significant benefits to the general public apart from security and military uses. The first application to be pursued was the development of satellites for assisting in weather forecasting. A second application involved remote observation of land and sea surfaces to gather imagery and other data of value in crop forecasting, resource management, environmental monitoring, and other applications. The U.S. and Soviet governments also developed their own satellite-based global positioning system (GPS)s, originally for military purposes, that could pinpoint a user's exact location, help in navigating from one point to another, and provide very precise time signals. These satellites quickly found numerous civilian uses in such areas as personal navigation, surveying and cartography, geology, air traffic control, and the operation of information-transfer networks. They illustrate a reality that has remained constant for the past half century—as space capabilities are developed, they often can be used for both military and civilian purposes.

Governments realized early on that the ability to observe Earth from space could provide significant benefits to the general public apart from security and military uses. The first application to be pursued was the development of satellites for assisting in weather forecasting. A second application involved remote observation of land and sea surfaces to gather imagery and other data of value in crop forecasting, resource management, environmental monitoring, and other applications. The U.S. and Soviet governments also developed their own satellite-based global positioning system (GPS)s, originally for military purposes, that could pinpoint a user's exact location, help in navigating from one point to another, and provide very precise time signals. These satellites quickly found numerous civilian uses in such areas as personal navigation, surveying and cartography, geology, air traffic control, and the operation of information-transfer networks. They illustrate a reality that has remained constant for the past half century—as space capabilities are developed, they often can be used for both military and civilian purposes.Another space application that began under government sponsorship but quickly moved into the private sector is the relay of voice, video, and data via orbiting satellites. Satellite telecommunications has developed into a multibillion-dollar business and is the one clearly successful area of commercial space activity. A related commercial space business is the provision of launches for private and government satellites. In 2004 a privately financed venture sent a piloted spacecraft to the lower edge of space for brief suborbital flights. Although technically a much less challenging achievement than carrying humans into orbit, its success was seen as an important step toward opening up space to commercial travel and eventually to tourism. Suggestions have been made that in the future other areas of space activity, including remote sensing and the capture of solar energy to provide electric power on Earth, could become successful businesses.

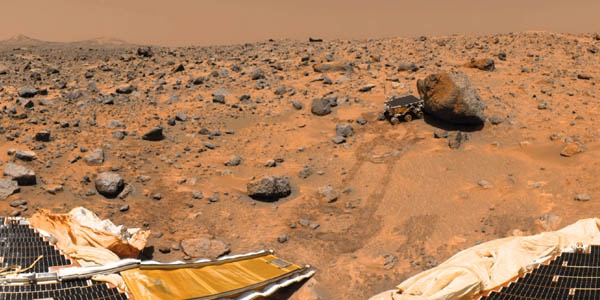

Most space activities have been pursued because they serve some utilitarian purpose, whether increasing knowledge or making a profit. Nevertheless, there remains a powerful underlying sense that it is important for humans to explore space for its own sake, “to see what is there.” Although the only voyages that humans have made away from the near vicinity of Earth—the Apollo flights to the Moon—were motivated by Cold War competition, there have been recurrent calls for humans to return to the Moon, travel to Mars, and visit other locations in the solar system and beyond. Until humans resume such journeys of exploration, robotic spacecraft will continue to serve in their stead to explore the solar system and probe the mysteries of the universe.

Major milestones

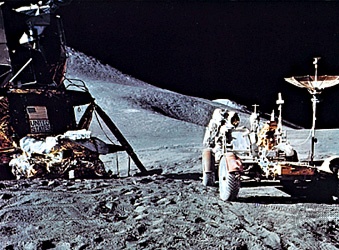

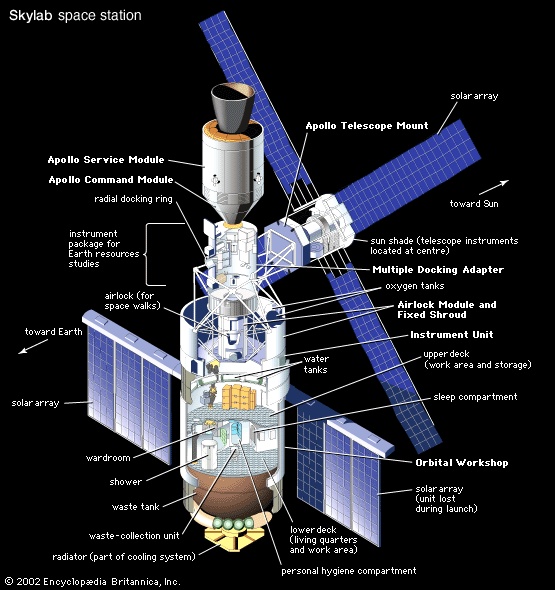

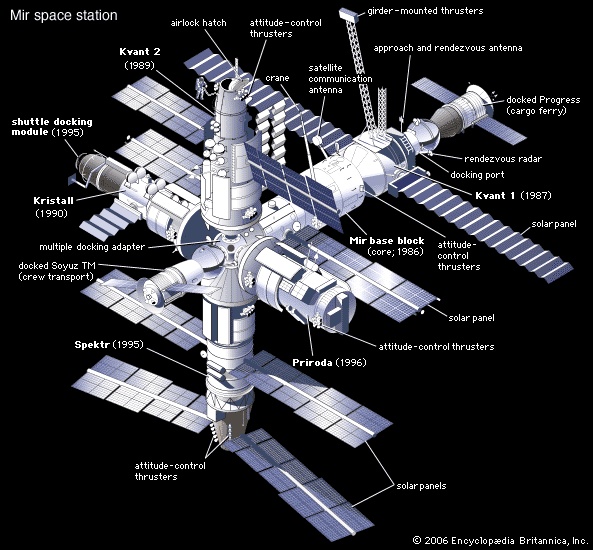

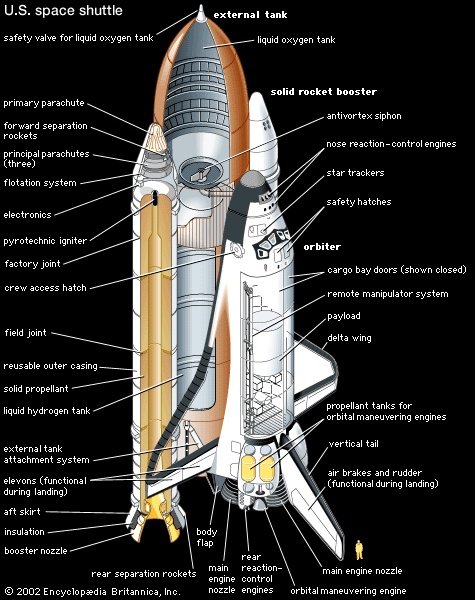

The first artificial Earth satellite, Sputnik 1, was launched by the Soviet Union on October 4, 1957. The first human to go into space, Yury Gagarin (Gagarin, Yury Alekseyevich), was launched, again by the Soviet Union, for a one-orbit journey around Earth on April 12, 1961. Within 10 years of that first human flight, American astronauts walked on the surface of the Moon. Apollo (Apollo program) 11 crew members Neil Armstrong (Armstrong, Neil) and Edwin (“Buzz”) Aldrin (Aldrin, Edwin Eugene, Jr.) made the first lunar landing on July 20, 1969. A total of 12 Americans on six separate Apollo missions set foot on the Moon between July 1969 and December 1972. Since then, no humans have left Earth orbit, but several hundred men and women have spent as many as 438 consecutive days in space. Starting in the early 1970s, a series of Soviet (Russian from December 1991) space stations (space station), the U.S. Skylab station, and numerous space shuttle flights have provided Earth-orbiting bases for varying periods of human occupancy and activity. With the development of the International Space Station (ISS) in the 1990s, the intent has been to have humans living and working in space on a permanent basis. The first ISS crew took up long-duration residence on November 2, 2000.

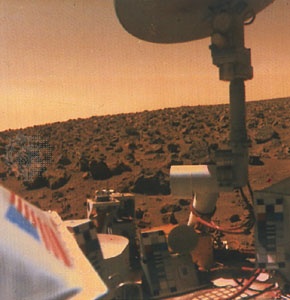

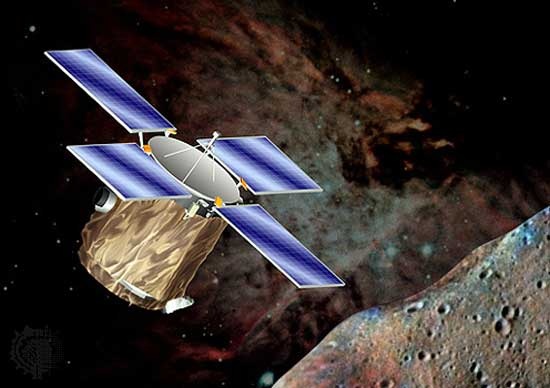

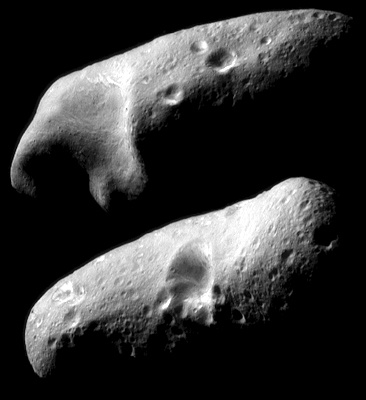

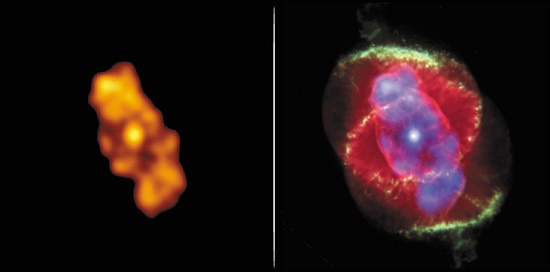

The first artificial Earth satellite, Sputnik 1, was launched by the Soviet Union on October 4, 1957. The first human to go into space, Yury Gagarin (Gagarin, Yury Alekseyevich), was launched, again by the Soviet Union, for a one-orbit journey around Earth on April 12, 1961. Within 10 years of that first human flight, American astronauts walked on the surface of the Moon. Apollo (Apollo program) 11 crew members Neil Armstrong (Armstrong, Neil) and Edwin (“Buzz”) Aldrin (Aldrin, Edwin Eugene, Jr.) made the first lunar landing on July 20, 1969. A total of 12 Americans on six separate Apollo missions set foot on the Moon between July 1969 and December 1972. Since then, no humans have left Earth orbit, but several hundred men and women have spent as many as 438 consecutive days in space. Starting in the early 1970s, a series of Soviet (Russian from December 1991) space stations (space station), the U.S. Skylab station, and numerous space shuttle flights have provided Earth-orbiting bases for varying periods of human occupancy and activity. With the development of the International Space Station (ISS) in the 1990s, the intent has been to have humans living and working in space on a permanent basis. The first ISS crew took up long-duration residence on November 2, 2000. Since 1957 Earth-orbiting satellites and robotic spacecraft journeying away from Earth have gathered valuable data about the Sun, Earth, other bodies in the solar system, and the universe beyond. Robotic spacecraft have landed on the Moon, Venus, Mars, and the asteroid Eros, have visited the vicinity of all the major planets, and have flown by the nuclei of comets, including Halley's Comet, traveling in the inner solar system. Scientists have used space-derived data to deepen human understanding of the origin and evolution of galaxies, stars, planets, and other cosmological phenomena.

Since 1957 Earth-orbiting satellites and robotic spacecraft journeying away from Earth have gathered valuable data about the Sun, Earth, other bodies in the solar system, and the universe beyond. Robotic spacecraft have landed on the Moon, Venus, Mars, and the asteroid Eros, have visited the vicinity of all the major planets, and have flown by the nuclei of comets, including Halley's Comet, traveling in the inner solar system. Scientists have used space-derived data to deepen human understanding of the origin and evolution of galaxies, stars, planets, and other cosmological phenomena. Significant milestones in space explorationOrbiting satellites also have provided, and continue to provide, important services to the everyday life of many people on Earth. Meteorologic satellites deliver information on short- and long-term weather patterns and their underlying causes. Other Earth-observation satellites remotely sense land and ocean areas, gathering data that improve management of Earth's resources. Telecommunications satellites allow essentially instantaneous transfer of voice, images, and data on a global basis. Satellites operated by the United States and Russia give precision navigation, positioning, and timing information that has become essential to many terrestrial users. Earth-observation satellites have also become extremely useful to the military authorities of several countries as complements to their land, sea, and air forces. (For a list of significant milestones in space exploration, see the table (Significant milestones in space exploration).)

As the many benefits of space activity have become evident, other countries have joined the Soviet Union and the United States in developing their own space programs. They include a number of western European countries operating both individually and, after 1975, cooperatively through the European Space Agency, as well as China, Japan, Canada, India, Israel, and Brazil. By the start of the 21st century, more than 30 countries had space agencies or other government bodies with substantial space activities.

History of space exploration

Prelude to spaceflight

Precursors in fiction and fact

Since ancient times, people around the world have studied the heavens and used their observations and explanations of astronomical phenomena for both religious and practical purposes. Some dreamed of leaving Earth to explore other worlds. For example, the French satirist Cyrano de Bergerac (Cyrano de Bergerac, Savinien) in the 17th century wrote Histoire comique des états et empires de la lune (1656) and Histoire comique des états et empires du soleil (1662; together in English as A Voyage to the Moon: With Some Account of the Solar World, 1754), describing fictional journeys to the Moon and the Sun. Two centuries later, the French author Jules Verne (Verne, Jules) and the English novelist and historian H.G. Wells (Wells, H.G.) infused their stories with descriptions of outer space and of spaceflight that were consistent with the best understanding of the time. Verne's De la Terre à la Lune (1865; From the Earth to the Moon) and Wells's The War of the Worlds (1898) and The First Men in the Moon (1901) used sound scientific principles to describe space travel and encounters with alien beings.

In order to translate these fictional images of space travel into reality, it was necessary to devise some practical means of countering the influence of Earth's gravity. By the beginning of the 20th century, the centuries-old technology of rockets had advanced to the point at which it was reasonable to consider their use to accelerate objects to a velocity sufficient to enter orbit around Earth or even to escape Earth's gravity and travel away from the planet.

Tsiolkovsky (Tsiolkovsky, Konstantin Eduardovich)

The first person to study in detail the use of rockets (rocket) for spaceflight was the Russian schoolteacher and mathematician Konstantin Tsiolkovsky (Tsiolkovsky, Konstantin Eduardovich). In 1903 his article “Exploration of Cosmic Space by Means of Reaction Devices” laid out many of the principles of spaceflight. Up to his death in 1935, Tsiolkovsky continued to publish sophisticated studies on the theoretical aspects of spaceflight. He never complemented his writings with practical experiments in rocketry, but his work greatly influenced later space and rocket research in the Soviet Union and Europe.

Goddard (Goddard, Robert Hutchings)

In the United States, Robert Hutchings Goddard (Goddard, Robert Hutchings) became interested in space exploration after reading works such as The War of the Worlds. Even as a young man, he dedicated himself to working on spaceflight. In his 1904 high-school graduation speech, he stated that “it is difficult to say what is impossible, for the dream of yesterday is the hope of today and the reality of tomorrow.” Goddard received his first two patents for rocket technology in 1914, and, with funding from the Smithsonian Institution, he published a theoretical treatise, A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes, in 1919. Goddard's claim that rockets could be used to send objects as far as the Moon was widely ridiculed in the public press, including The New York Times (which published a retraction on July 17, 1969, the day after the launch of the first manned mission to the Moon). Thereafter, the already shy Goddard conducted much of his work in secret, preferring to patent rather than publish his results. This approach limited his influence on the development of American rocketry, although early rocket developers in Germany took notice of his work.

In the 1920s, as a professor of physics at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, Goddard began to experiment with liquid-fueled rockets. His first rocket, launched in Auburn, Massachusetts, on March 16, 1926, rose 12.5 metres (41 feet) and traveled 56 metres (184 feet) from its launching place. The noisy character of his experiments made it difficult for Goddard to continue work in Massachusetts. With support from aviator Charles A. Lindbergh (Lindbergh, Charles A.) and financial assistance from the philanthropic Daniel Guggenheim (Guggenheim, Meyer) Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics, he moved to Roswell, New Mexico, where from 1930 to 1941 he built engines and launched rockets of increasing complexity.

Oberth (Oberth, Hermann)

The third widely recognized pioneer of rocketry (rocket), Hermann Oberth (Oberth, Hermann), was by birth a Romanian but by nationality a German. Reading Verne's From the Earth to the Moon as a youth inspired him to study the requirements for interplanetary travel. Oberth's 1922 doctoral dissertation on rocket-powered flight was rejected by the University of Heidelberg for being too speculative, but it became the basis for his classic 1923 book Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen (“The Rocket into Interplanetary Space”). The work explained the mathematical theory of rocketry, applied the theory to rocket design, and discussed the possibility of constructing space stations and of traveling to other planets.

In 1929 Oberth published a second influential book, Wege Zur Raumschiffahrt (Ways to Spaceflight). His works led to the creation of a number of rocket clubs in Germany as enthusiasts tried to turn Oberth's ideas into practical devices. The most important of these groups historically was the Verein für Raumschiffahrt (VfR; “Society for Spaceship Travel”), which had as a member the young Wernher von Braun (Braun, Wernher von). Although his work was crucial in stimulating the development of rocketry in Germany, Oberth himself had only a limited role in that development. Alone among the rocket pioneers, Oberth lived to see his ideas become reality: he was Braun's guest at the July 16, 1969, launch of Apollo 11.

Other space pioneers

Although Tsiolkovsky, Goddard, and Oberth are recognized as the most influential of the first-generation space pioneers, others made contributions in the early decades of the 20th century. For example, the Frenchman Robert Esnault-Pelterie (Esnault-Pelterie, Robert) began work on the theoretical aspects of spaceflight as early as 1907 and subsequently published several major books on the topic. He, like Tsiolkovsky in the Soviet Union and Oberth in Germany, was an effective publicist regarding the potential of space exploration. In Austria, Eugen Sänger (Sänger, Eugen) worked on rocket engines and in the late 1920s proposed developing a “rocket plane” that could reach a speed exceeding 10,000 km (more than 6,000 miles) per hour and an altitude of more than 65 km (40 miles). Interested in Sänger's work, Nazi Germany in 1936 invited him to continue his investigations in that country.

Early rocket development

Germany

It was space exploration that motivated the members of the German VfR to build their rockets, but in the early 1930s their work came to the attention of the German military. In 1932 Wernher von Braun (Braun, Wernher von), at age 20, became chief engineer of a rocket-development team for the German army. After Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933, Braun was named the civilian head of that team, under the military command of Walter Robert Dornberger (Dornberger, Walter Robert). To give Braun's engineers the needed space and secrecy for their work, the German government erected a development and test centre at Peenemünde on the coast of the Baltic Sea. There they developed, among other devices, the V-2 (V-2 missile) (originally designated the A-4) ballistic missile. First launched successfully in 1942, the V-2 was used on targets in Europe beginning in September 1944. Although built as a weapon of war, the V-2 later served as the predecessor of many of the rockets used in the early space programs of the United States and the Soviet Union. As World War II neared its end in early 1945, Braun and many of his associates chose to surrender to the United States, where they believed they would likely receive support for their rocket research and space exploration plans. Later in the year, they were taken to the United States, as were their engineering plans and the parts needed to construct a number of V-2s. The German rocket team played a central role in the early development of space launchers for the United States.

It was space exploration that motivated the members of the German VfR to build their rockets, but in the early 1930s their work came to the attention of the German military. In 1932 Wernher von Braun (Braun, Wernher von), at age 20, became chief engineer of a rocket-development team for the German army. After Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933, Braun was named the civilian head of that team, under the military command of Walter Robert Dornberger (Dornberger, Walter Robert). To give Braun's engineers the needed space and secrecy for their work, the German government erected a development and test centre at Peenemünde on the coast of the Baltic Sea. There they developed, among other devices, the V-2 (V-2 missile) (originally designated the A-4) ballistic missile. First launched successfully in 1942, the V-2 was used on targets in Europe beginning in September 1944. Although built as a weapon of war, the V-2 later served as the predecessor of many of the rockets used in the early space programs of the United States and the Soviet Union. As World War II neared its end in early 1945, Braun and many of his associates chose to surrender to the United States, where they believed they would likely receive support for their rocket research and space exploration plans. Later in the year, they were taken to the United States, as were their engineering plans and the parts needed to construct a number of V-2s. The German rocket team played a central role in the early development of space launchers for the United States. United States

In 1936, as Braun was developing rockets for the German military, several young American engineers led by graduate student Frank Malina began working on rocketry at the Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory of the California Institute of Technology (GALCIT). Malina's group was supported by the eminent aerodynamicist Theodore von Kármán (Kármán, Theodore von), GALCIT's director, and it included Chinese engineer Qian Xuesen (Ch'ien Hsüeh-sen), who in the 1950s returned home to become one of the pioneers of rocketry in China. In 1943 Malina and his associates began calling their group the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), a name that was formally adopted the following year. JPL soon became a centre for missile research and development for the U.S. Army. Following World War II, those weapons were adapted for use in early U.S. space experiments. After 1958, when it became part of the newly established National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), JPL adapted itself to being the leading U.S. centre for solar system exploration.

Soviet Union (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics)

In the U.S.S.R., the government took an interest in rockets as early as 1921 with the founding of a military facility devoted to rocket research. Over the next decade, that centre was expanded and renamed the Gas Dynamics Laboratory. There in the early 1930s, Valentin Glushko (Glushko, Valentin Petrovich) carried out pioneering work on rocket engines. Meanwhile, other rocket enthusiasts in the Soviet Union organized into societies that by 1931 had consolidated into an organization known as GIRD (the abbreviation in Russian for “Group for the Study of Reactive Motion”), with branches in Moscow and Leningrad. Emerging as leaders of the Moscow branch were the aeronautical engineer Sergey Korolyov (Korolyov, Sergey Pavlovich), who had become interested in spaceflight at a young age, and the early space visionary Fridrikh Tsander. Korolyov and a colleague, Mikhail Tikhonravov, on August 17, 1933, launched the first Soviet liquid-fueled rocket. Later that year, the Moscow and Leningrad branches of GIRD were combined with the Gas Dynamics Laboratory to form the military-controlled Rocket Propulsion Research Institute (RNII), which five years later became Scientific-Research Institute 3 (NII-3). In its early years, the organization did not work directly on space technology, but ultimately it played a central role in Soviet rocket development.

Korolyov was arrested in 1937 as part of the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin's great purges (Stalin, Joseph) of intellectuals and was sent to a Siberian prison. After Stalin recognized the imprudence of removing the best technical people from the Soviet war effort, Korolyov was transferred to a prison-based design bureau, where he spent most of World War II working on weapons, although not on large rockets. By the end of the war, Stalin had become interested in ballistic missiles, and he sent a team, which included Korolyov, on visits to Germany to investigate the V-2 program. A number of German engineers were relocated to the Soviet Union in the aftermath of the war, but they did not play a central role in postwar Soviet rocket development; most returned to Germany in the early 1950s.

Preparing for spaceflight

Between 1946 and 1951, the U.S. Army (United States Army, The) conducted test firings of captured German V-2 rockets at White Sands, New Mexico. These sounding-rocket flights reached high altitudes (120–200 km 【75–125 miles】) before falling back to Earth. Although the primary purpose of the tests was to advance rocket technology, the army invited American scientists interested in high-altitude research to put experiments aboard the V-2s. An Upper Atmosphere Research Panel, chaired by the physicist James Van Allen (Van Allen, James A.), was formed to coordinate the scientific use of these rocket launchings. The panel had a central role in the early years of American space science, which focused on experiments on solar and stellar ultraviolet radiation, the aurora, and the nature of the upper atmosphere. As the supply of V-2s dwindled, other U.S.-built sounding rockets such as the WAC Corporal, Aerobee, and Viking were put into use. In other countries, particularly the Soviet Union, rocket-based upper-atmosphere research also took place after World War II.

Between 1946 and 1951, the U.S. Army (United States Army, The) conducted test firings of captured German V-2 rockets at White Sands, New Mexico. These sounding-rocket flights reached high altitudes (120–200 km 【75–125 miles】) before falling back to Earth. Although the primary purpose of the tests was to advance rocket technology, the army invited American scientists interested in high-altitude research to put experiments aboard the V-2s. An Upper Atmosphere Research Panel, chaired by the physicist James Van Allen (Van Allen, James A.), was formed to coordinate the scientific use of these rocket launchings. The panel had a central role in the early years of American space science, which focused on experiments on solar and stellar ultraviolet radiation, the aurora, and the nature of the upper atmosphere. As the supply of V-2s dwindled, other U.S.-built sounding rockets such as the WAC Corporal, Aerobee, and Viking were put into use. In other countries, particularly the Soviet Union, rocket-based upper-atmosphere research also took place after World War II.In the early 1950s, scientists began planning a coordinated international investigation of Earth, to be called the International Geophysical Year (IGY), that would be held in 1957–58 under the auspices of the International Council of Scientific Unions. By this time, progress in rocket development had advanced such that orbiting of an artificial satellite around Earth by 1957 seemed feasible. At the urging of American scientists, IGY planners in 1954 called for scientifically instrumented satellites to be launched as part of IGY activities. Soon thereafter, the governments of the Soviet Union and the United States each announced plans to do so.

In the years following World War II, the United States and the U.S.S.R. became political and military competitors in what soon was being called the Cold War. Because the Soviet Union was a closed society, U.S. leaders gave high priority to developing technology that could help gather intelligence on military preparations within the Soviet borders. As orbiting satellites neared realization, the idea of equipping such satellites with cameras and flying them over Soviet territory became more attractive to U.S. planners, and the U.S. Air Force began work on a reconnaissance satellite project. Still unresolved, however, was the question of whether it would violate national sovereignty to fly over a country's territory in orbit, above most of the atmosphere. One reason the U.S. government had committed itself to the IGY satellite program was that it wanted to establish the principle that outer space was not subject to claims of territorial sovereignty and thus that an orbiting satellite could pass freely over any point on Earth. Such overflights were essential if reconnaissance satellites were to have intelligence value.

As scientific and military planners contemplated initial space projects and engineers worked on developing the needed launch vehicles, the idea that humans would soon begin the exploration of space entered popular imagination. In Europe, since the 1930s, the British Interplanetary Society had been actively promoting the idea that human space travel was soon to happen. American movies such as The Day the Earth Stood Still (1950), Destination Moon (1950), and When Worlds Collide (1951) contained vivid images of such journeys. Reports were widespread of sightings of unidentified flying objects (unidentified flying object) (UFOs), which were thought by some to be spacecraft from alien worlds.

As scientific and military planners contemplated initial space projects and engineers worked on developing the needed launch vehicles, the idea that humans would soon begin the exploration of space entered popular imagination. In Europe, since the 1930s, the British Interplanetary Society had been actively promoting the idea that human space travel was soon to happen. American movies such as The Day the Earth Stood Still (1950), Destination Moon (1950), and When Worlds Collide (1951) contained vivid images of such journeys. Reports were widespread of sightings of unidentified flying objects (unidentified flying object) (UFOs), which were thought by some to be spacecraft from alien worlds.Authors such as Isaac Asimov (Asimov, Isaac), Robert A. Heinlein (Heinlein, Robert A), and Arthur C. Clarke (Clarke, Sir Arthur C.) both discussed the reality of space technology in popular writings and constructed believable science-fiction stories based on its use. A central figure in popularization efforts within the United States was Braun (Braun, Wernher von). A charismatic spokesman for the idea of space travel, Braun, in a series of talks, books, magazine articles, and television appearances during the 1950s, reached millions of people with his ideas for establishing orbiting space stations and human travel to the Moon and Mars. The efforts of Braun and other popularizers helped create a receptive climate for initial government proposals to undertake space activities and, particularly, to put humans in space.

From Sputnik to Apollo

The first satellites

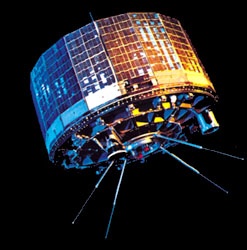

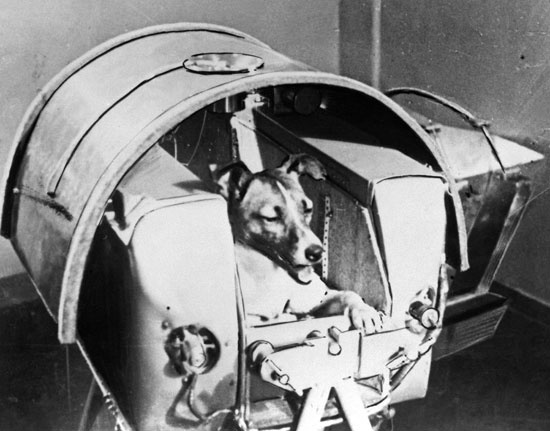

Although Soviet plans to orbit a satellite during the IGY had been discussed extensively in technical circles, the October 4, 1957, launch of Sputnik 1 came as a surprise, and even a shock, to most people. Prior to the launch, skepticism had been widespread about the U.S.S.R.'s technical capabilities to develop both a sophisticated scientific satellite and a rocket powerful enough to put it into orbit. Under Korolyov's direction, however, the Soviet Union had been building an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), with engines designed by Glushko, that was capable of delivering a heavy nuclear warhead to American targets. That ICBM, called the R-7 or Semyorka (“Number 7”), was first successfully tested on August 21, 1957, which cleared the way for its use to launch a satellite. Fearing that development of the elaborate scientific satellite intended as the Soviet IGY contribution would keep the U.S.S.R. from being the first into space, Korolyov and his associates, particularly Tikhonravov, designed a much simpler 83.6-kg (184-pound) sphere carrying only two radio transmitters and four antennas. After the success of the R-7 in August, that satellite was rushed into production and became Sputnik 1. A second, larger satellite carrying scientific instruments and the dog Laika, the first living creature in orbit, was launched November 3. The even larger, instrumented spacecraft originally intended to be the first Soviet satellite went into orbit in May 1958 as Sputnik 3. (For additional information on Korolyov's contribution to the Soviet space program, see Energia.)

Although Soviet plans to orbit a satellite during the IGY had been discussed extensively in technical circles, the October 4, 1957, launch of Sputnik 1 came as a surprise, and even a shock, to most people. Prior to the launch, skepticism had been widespread about the U.S.S.R.'s technical capabilities to develop both a sophisticated scientific satellite and a rocket powerful enough to put it into orbit. Under Korolyov's direction, however, the Soviet Union had been building an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), with engines designed by Glushko, that was capable of delivering a heavy nuclear warhead to American targets. That ICBM, called the R-7 or Semyorka (“Number 7”), was first successfully tested on August 21, 1957, which cleared the way for its use to launch a satellite. Fearing that development of the elaborate scientific satellite intended as the Soviet IGY contribution would keep the U.S.S.R. from being the first into space, Korolyov and his associates, particularly Tikhonravov, designed a much simpler 83.6-kg (184-pound) sphere carrying only two radio transmitters and four antennas. After the success of the R-7 in August, that satellite was rushed into production and became Sputnik 1. A second, larger satellite carrying scientific instruments and the dog Laika, the first living creature in orbit, was launched November 3. The even larger, instrumented spacecraft originally intended to be the first Soviet satellite went into orbit in May 1958 as Sputnik 3. (For additional information on Korolyov's contribution to the Soviet space program, see Energia.)After President Eisenhower (Eisenhower, Dwight D.), in May 1955, had committed the United States to an IGY satellite, the army, navy, and air force competed for the assignment. (No civilian organization existed that was capable of developing the launch vehicle needed.) The mission was assigned to the Naval Research Laboratory, rather than to the army's Redstone Arsenal, where Braun worked, so that the work would not interfere with Redstone's higher-priority development of ballistic missiles. The navy project, called Vanguard, would use a new launch vehicle based on modified Viking and Aerobee sounding rockets to orbit a small scientific satellite. Vanguard made slow progress over the subsequent two years, but, after Sputnik's success, the White House pressed to have the satellite launched as quickly as possible. On December 6, 1957, the Vanguard rocket rose only slightly off its launch pad before exploding and sending the satellite not into orbit but onto a Florida beach.

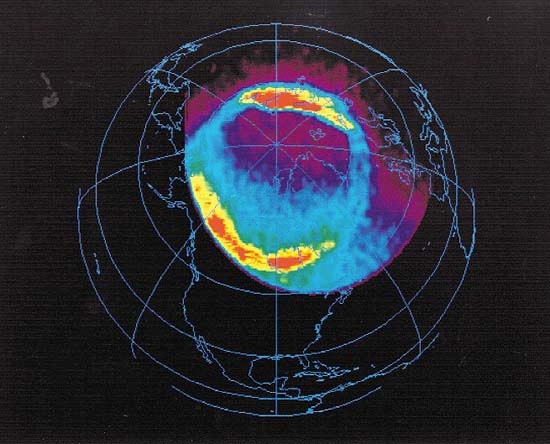

Braun and his army superiors had not agreed with the decision to assign the satellite mission to the navy. After the launches of the first two Sputniks, they secured permission to attempt their own satellite launch. In anticipation of such a situation, they had kept in touch with JPL and Van Allen and so were able to prepare a satellite quickly. On January 31, 1958, Braun's Jupiter-C launch vehicle, a modified Redstone ballistic missile, carried into orbit Explorer 1, the first U.S. satellite. Designed at JPL, Explorer 1 carried Van Allen's experiment to measure cosmic rays (cosmic ray). The results from this experiment and similar ones aboard other U.S. and Soviet satellites launched that same year revealed that Earth was surrounded by two zones of radiation, now known as the Van Allen radiation belts (Van Allen radiation belt), comprising energetic particles trapped by Earth's magnetic field.

Braun and his army superiors had not agreed with the decision to assign the satellite mission to the navy. After the launches of the first two Sputniks, they secured permission to attempt their own satellite launch. In anticipation of such a situation, they had kept in touch with JPL and Van Allen and so were able to prepare a satellite quickly. On January 31, 1958, Braun's Jupiter-C launch vehicle, a modified Redstone ballistic missile, carried into orbit Explorer 1, the first U.S. satellite. Designed at JPL, Explorer 1 carried Van Allen's experiment to measure cosmic rays (cosmic ray). The results from this experiment and similar ones aboard other U.S. and Soviet satellites launched that same year revealed that Earth was surrounded by two zones of radiation, now known as the Van Allen radiation belts (Van Allen radiation belt), comprising energetic particles trapped by Earth's magnetic field.Initial satellite launches were scientific in character, but U.S. government interest in reconnaissance satellites persisted. In February 1958, President Eisenhower authorized the development, under conditions of great secrecy, of such a spacecraft. The project, which came to be called Corona, would take pictures over the Soviet Union and return them to Earth by dropping the exposed film in a capsule that would be snatched out of the air as it parachuted back from space. After 12 failures, the first successful Corona mission took place on August 18, 1960; the returned film contained images of many previously unknown Soviet airfields and missile sites.

Development of space organizations

United States

As part of its response to the first Sputnik launches, the United States government debated how best to organize itself for its space activities. At the time, the military services, particularly the air force and the army, hoped that they would have a leading role in space. As an alternative to this rivalry between the services, President Eisenhower in February 1958 created the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and assigned it responsibility for all U.S. space projects. Soon afterward, he decided to separate civilian from military space efforts and proposed the creation of a National Aeronautics and Space Administration to manage the civilian segment. After approval by Congress, NASA began operation on October 1, 1958. DARPA was not successful in establishing itself as a military space agency. By 1960, after the army had been obliged to relinquish control of JPL and Braun's rocket team to NASA management, the air force had emerged as the leading military service for space.

Eisenhower also decided to create a separate organization to manage the secret reconnaissance satellite program. This effort resulted in the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), jointly directed by the Department of Defense and the Central Intelligence Agency. The very existence of this organization was kept secret until 1992. The NRO operated the initial Corona program until 1972. It continued to manage the development of successor photointelligence satellite systems of increasing technological sophistication and also developed radar-surveillance and electronic-signals-collection satellites. All were operated under conditions of the highest secrecy.

After it received its mandate to send Americans to the Moon, NASA grew into a large organization. From its headquarters in Washington, D.C., it operated 10 field centres established throughout the United States to carry out research and technology development and to manage the various universities and industrial contractors involved in the U.S. civilian space program. At the peak of the Apollo program, NASA had 34,000 employees; by the end of the 20th century, this labour force had shrunk to 19,000, but NASA remained by far the largest space agency in the world.

The air force had no separate organization for space until 1982, when the U.S. Air Force (United States Air Force, The) Space Command was created to manage its military space operations, which involved the use of satellites for meteorology, communication, navigation, and early warning of missile attack. The other U.S. military services soon created similar organizations to administer their smaller space activities. In 1985 these organizations were brought under a unified U.S. Space Command, dominated by the air force, which was responsible for 85 percent of military space activities. Research and development efforts related to military space programs were managed by various government laboratories and carried out primarily by American industry.

Soviet Union

In contrast to the United States, the Soviet Union had no separate, publicly acknowledged space agency. For 35 years after Sputnik, various design bureaus—state-controlled organizations that actually conceived and developed aircraft and space systems—had great influence within the Soviet system. (For information on the history of specific Soviet aerospace design bureaus, see Energia, MiG, Sukhoy, and Tupolev.) Rivalry between those bureaus and their heads, who were known as chief designers, was a constant reality and posed an obstacle to a coherent Soviet space program. Space policy decisions were made by the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party as well as the Soviet government's Council of Ministers. After 1965 the government's Ministry of General Machine Building was assigned responsibility for managing all Soviet space and missile programs; the Ministry of Defense was also quite influential in shaping space efforts. A separate military branch, the Strategic Missile Forces, was in charge of space launchers and strategic missiles. Various institutes of the Soviet Academy of Sciences, particularly the Institute for Space Research (IKI), proposed and managed scientific missions.

Only after the dissolution of the U.S.S.R did Russia create a civilian organization for space activities. Formed in February 1992, the Russian Space Agency acted as a central focus for the country's space policy and programs. Although it began as a small organization that dealt with international contacts and the setting of space policies, it quickly took on increasing responsibility for the management of nonmilitary space activities and, as an added charge, aviation efforts. It later was renamed the Russian Aviation and Space Agency.

Europe

In 1961, within four years of the launch of the first U.S. and Soviet satellites, the government of France created the French Space Agency (CNES), which grew to become the largest national organization of its kind in Europe. Gradually other European countries formed government or government-sponsored organizations for space, among them the German Aerospace Center (DLR), the British National Space Centre (BNSC), and the Italian Space Agency (ASI). Still others included space as part of their science or technology ministries.

In 1964 a European Space Research Organisation (ESRO), created at the initiative of European scientists to pool government resources in support of space science, began operations. Ten western European countries and Australia joined the organization. In the same year, a parallel European Launcher Development Organisation (ELDO), which had seven European member states, was established to develop a space launch vehicle for Europe. Whereas ESRO was successful in mounting a series of science missions, many in collaboration with NASA, ELDO failed in attempts to design and launch a European rocket. In 1975 a new European Space Agency (ESA) was formed from ESRO and ELDO to carry out both of their tasks. At the beginning of the 21st century, ESA had 15 member states—Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Norway, The Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. Canada also participated in some ESA projects. With a budget that made it the world's second largest civilian space agency, ESA carried out a comprehensive program in space science, applications, and infrastructure development. In particular, the Ariane series of expendable launch vehicles was developed under ESA auspices, with France taking the leading role. These launchers proved to be extremely reliable, and they gave Europe independent access to space and a leading position in the commercial space launch industry.

Japan

In Japan the University of Tokyo created an Institute of Space and Astronautical Science (ISAS) in 1964. This small group undertook the development of scientific spacecraft and the vehicles needed to launch them, and it launched Japan's first satellite, Ōsumi, in 1970. In 1981 oversight of ISAS was transferred to the Japanese Ministry of Education. In 1969 the Japanese government founded a National Space Development Agency (NASDA), which subsequently undertook a comprehensive program of space technology and satellite development and built a large launch vehicle, called the H-II, for those satellites. In 2001 both ISAS and NASDA came under the control of the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

China

China's space program evolved largely in secret, under the joint control of the Chinese military and the Commission on Science, Technology, and Industry for the National Defense. After the communist takeover of 1949, Qian Xuesen, who had worked at GALCIT in the 1940s and helped found JPL, returned to China, where he became the guiding figure in the development of Chinese missiles and launch vehicles, both originally derived from a Soviet ICBM. China developed a family of Long March boosters, which are used domestically and serve as competitors in the international commercial space launch market. Its space development has concentrated on applications such as communications satellites and Earth-observation satellites for civilian and military use. In 1998 an independent Chinese Aerospace Corporation was established to oversee most Chinese space-equipment manufacturers.

China initiated its own human spaceflight program in 1992. The spacecraft, called Shenzhou, that it developed for the effort was modeled on Russia's time-tested Soyuz design (see the section Soyuz (space exploration) below), but it relied heavily on Chinese-developed technologies and manufacturing. Following four years of unmanned spacecraft tests, China launched its first indigenous astronaut, an air force pilot, into orbit on October 15, 2003. In so doing, it became the third country—after the former Soviet Union and the United States—to achieve human spaceflight.

International participation

A number of international organizations are involved in space activities. The United Nations General Assembly established a Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space in 1959 to discuss scientific, technical, and legal issues related to international space activities; 61 countries were members of the committee in 2001. The committee has provided the forum for the development of five treaties and a number of declarations of principles related to space activities. The most important of them is the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which sets forth the general legal principles governing the uses of space. Other parts of the UN system, most notably the International Telecommunications Union (International Telecommunication Union) (ITU), are engaged in space-related concerns. The ITU is responsible for allocation of radio frequencies and orbital locations for various satellites providing public and commercial services.

At the initiative of the United States, an International Telecommunications Satellite Consortium ( Intelsat) was founded in 1964 to develop and operate a global system of communications satellites. By 1969 the organization had established a system of satellites with global coverage; in the late 1980s it provided services to more than 200 countries and territories. Intelsat membership grew to 144 countries before a decision was made in 1999 to change the ownership of the organization from national governments to the private sector. A similar consortium, the International Maritime Satellite Organization (Inmarsat), was established as an intergovernmental organization in 1979 to supply maritime and other mobile communications services via satellite; it also was later transformed into a privately owned entity. In addition, a number of regional organizations have been created to operate communication and meteorologic satellites.

Involvement of industry

Building the systems and components needed to carry out both government and commercial space programs has required the participation of private industry, and a number of firms have grown to have substantial space involvement. Often these firms have also been major suppliers of aviation and defense products, a reflection of the common technological foundation for what has become known as the aerospace industry. Other private firms have specialized in providing space-based services in such areas as telecommunications and Earth observation.

The first human spaceflights

During the 1950s, space planners in both the Soviet Union and the United States anticipated the launching of a human being into orbit as soon as the required launch vehicle and spacecraft could be developed and tested. Much of the initial thinking focused on some form of piloted space plane, which, after being launched atop a rocket, could maneuver in orbit and then return to Earth, gliding to a horizontal landing.

In the United States, the air force developed a rocket-powered experimental aircraft, the X-15, which, after being dropped from an in-flight B-52 bomber, could reach altitudes as high as 108 km (67 miles), the edge of outer space. Nevertheless, the X-15 could not achieve the velocity and altitude needed for orbital flight. That was the mission of Dyna-Soar, another air force project. Dyna-Soar was to be a piloted reusable delta-winged vehicle that would be launched into orbit by a modified Titan (Titan rocket) ICBM and could carry out either bombing or reconnaissance missions over the Soviet Union or intercept a Soviet satellite in orbit. Although a full-scale vehicle was built and six people were chosen to train as Dyna-Soar crew, the project was canceled in 1963.

In the United States, the air force developed a rocket-powered experimental aircraft, the X-15, which, after being dropped from an in-flight B-52 bomber, could reach altitudes as high as 108 km (67 miles), the edge of outer space. Nevertheless, the X-15 could not achieve the velocity and altitude needed for orbital flight. That was the mission of Dyna-Soar, another air force project. Dyna-Soar was to be a piloted reusable delta-winged vehicle that would be launched into orbit by a modified Titan (Titan rocket) ICBM and could carry out either bombing or reconnaissance missions over the Soviet Union or intercept a Soviet satellite in orbit. Although a full-scale vehicle was built and six people were chosen to train as Dyna-Soar crew, the project was canceled in 1963.Rather than base their human spaceflight programs on space planes, the Soviet Union and the United States, in their desire to put people into space as quickly as possible, opted for a less technically demanding ballistic approach. A person would ride in a capsulelike spacecraft atop a rocket to achieve orbit. At the end of the flight, another rocket (called a retro-rocket) would slow down the spacecraft enough for it to fall back to Earth on a ballistic trajectory. To accomplish this feat, the spacecraft would have to survive the intense heat caused by reentering the atmosphere at a high speed and then carry its passenger safely back to Earth's surface.

Vostok

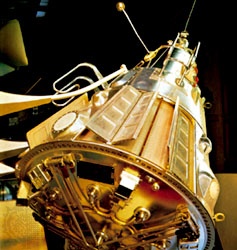

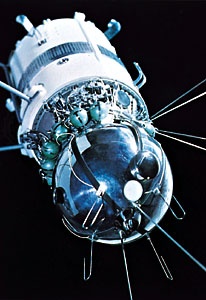

Soon after the success of the first Sputniks, Korolyov (Korolyov, Sergey Pavlovich) and his associate Tikhonravov began work on the design of an orbital spacecraft that could be used for two purposes. One was to conduct photoreconnaissance missions and then return the exposed film to Earth. The other was to serve as a vehicle for the first human spaceflight missions, in which a human being would replace the reconnaissance camera. The spacecraft was known as Object K, but it was called Vostok when it was used to carry a human into space. Vostok had two sections—a spherical capsule in which the person would ride and a conical module that contained the instruments needed for its flight. The spacecraft was large for the time, weighing 4.73 metric tons. The crew capsule was completely covered by a thermal coating to protect it during reentry. Vostok was designed so that the human aboard need not touch any control from launch to touchdown; he would be essentially just a passenger. Nor would he land with the spacecraft. Rather, he would be ejected from it at an altitude of 7 km (4.3 miles) and parachute to dry land, while the spacecraft landed nearby with its own parachutes.

Soon after the success of the first Sputniks, Korolyov (Korolyov, Sergey Pavlovich) and his associate Tikhonravov began work on the design of an orbital spacecraft that could be used for two purposes. One was to conduct photoreconnaissance missions and then return the exposed film to Earth. The other was to serve as a vehicle for the first human spaceflight missions, in which a human being would replace the reconnaissance camera. The spacecraft was known as Object K, but it was called Vostok when it was used to carry a human into space. Vostok had two sections—a spherical capsule in which the person would ride and a conical module that contained the instruments needed for its flight. The spacecraft was large for the time, weighing 4.73 metric tons. The crew capsule was completely covered by a thermal coating to protect it during reentry. Vostok was designed so that the human aboard need not touch any control from launch to touchdown; he would be essentially just a passenger. Nor would he land with the spacecraft. Rather, he would be ejected from it at an altitude of 7 km (4.3 miles) and parachute to dry land, while the spacecraft landed nearby with its own parachutes.After a series of five test flights carrying dogs and human dummies, the first person lifted into space in Vostok 1 atop a modified R-7 rocket on April 12, 1961, from the Soviet launch site at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. The passenger, Yury Gagarin (Gagarin, Yury Alekseyevich), who was by that time being called a cosmonaut, was a 27-year-old Russian test pilot. After firing of the retro-rocket 78 minutes into the mission, the crew capsule separated from the instrument module—although not without problems—and Gagarin parachuted to a soft landing 108 minutes after his launch. He had reported during the mission “I feel fine” and showed no ill effects from his one-orbit trip around the globe.

There were five additional one-person Vostok missions. In August 1961, Gherman Titov (Titov, Gherman Stepanovich) at age 25 (still the youngest person ever to fly in space) completed 17 orbits of Earth in Vostok 2. He became ill with space sickness (the equivalent of motion sickness on Earth) during the flight, an incident that caused a one-year delay in Vostok flights while Soviet physicians investigated the possibility that humans could not survive for extended times in the space environment. In August 1962, two Vostoks, 3 and 4, were orbited at the same time and came within 6.5 km (4 miles) of one another. This dual mission was repeated in June 1963; aboard the Vostok 6 spacecraft was Valentina Tereshkova (Tereshkova, Valentina), the first woman to fly in space.

Mercury

The initial U.S. effort to launch a human into space was known as Project Mercury (Mercury). It was carried out by NASA, which had been given that responsibility over air force objections. NASA engineers, led by Robert Gilruth and Maxime Faget (Faget, Max), designed a small cone-shaped capsule for the mission. Compared with the nearly five-metric-ton Vostok, it weighed 1.94 metric tons. Unlike the Soviet approach, in which a cosmonaut was orbited on the first human spaceflight, NASA planned several suborbital test flights in which an astronaut would be in space for only a few minutes of his 15-minute up-and-down ride. Only after the Mercury equipment was checked and the effects of suborbital flight on the human body were measured would the United States commit to an orbital flight attempt. The Mercury capsule would parachute with its passenger all the way back to Earth's surface, to land in the ocean and be recovered by navy ships. Also in contrast to Vostok, the Mercury capsule was designed to allow the astronaut to control some aspects of its flight while in space.

The United States used chimpanzees (chimpanzee), rather than dogs, as test subjects prior to human flights. In what was intended to be the final test flight before a human launch, the chimpanzee Ham rode a suborbital trajectory on January 31, 1961, using a Redstone rocket developed by Braun's team. Because the flight had experienced minor problems, Braun insisted on one more test flight with an unoccupied dummy spacecraft. If instead, as originally scheduled, that March 1961 flight had carried an astronaut, the United States would have been first with a human in space, although not in orbit. Alan B. Shepard, Jr. (Shepard, Alan B., Jr.), made the first manned Mercury flight atop a Redstone rocket on May 5, 1961. A second suborbital Mercury mission, carrying Virgil I. Grissom (Grissom, Virgil I.), followed in July.

The United States used chimpanzees (chimpanzee), rather than dogs, as test subjects prior to human flights. In what was intended to be the final test flight before a human launch, the chimpanzee Ham rode a suborbital trajectory on January 31, 1961, using a Redstone rocket developed by Braun's team. Because the flight had experienced minor problems, Braun insisted on one more test flight with an unoccupied dummy spacecraft. If instead, as originally scheduled, that March 1961 flight had carried an astronaut, the United States would have been first with a human in space, although not in orbit. Alan B. Shepard, Jr. (Shepard, Alan B., Jr.), made the first manned Mercury flight atop a Redstone rocket on May 5, 1961. A second suborbital Mercury mission, carrying Virgil I. Grissom (Grissom, Virgil I.), followed in July. John H. Glenn, Jr. (Glenn, John H., Jr.), became the first American astronaut to orbit Earth in his three-orbit mission on February 20, 1962. His Mercury spacecraft was launched by a modified air force Atlas (Atlas rocket) ICBM. Three more one-man Mercury orbital flights, carrying astronauts M. Scott Carpenter (Carpenter, M. Scott), Walter M. Schirra, Jr. (Schirra, Walter M., Jr.), and L. Gordon Cooper, Jr. (Cooper, L. Gordon, Jr.), were conducted, the last being a 22-orbit mission in May 1963.

John H. Glenn, Jr. (Glenn, John H., Jr.), became the first American astronaut to orbit Earth in his three-orbit mission on February 20, 1962. His Mercury spacecraft was launched by a modified air force Atlas (Atlas rocket) ICBM. Three more one-man Mercury orbital flights, carrying astronauts M. Scott Carpenter (Carpenter, M. Scott), Walter M. Schirra, Jr. (Schirra, Walter M., Jr.), and L. Gordon Cooper, Jr. (Cooper, L. Gordon, Jr.), were conducted, the last being a 22-orbit mission in May 1963. Gemini and Voskhod

In 1961 President Kennedy announced that the United States would send people to the Moon “before this decade is out.” In order to test many of the techniques that would be needed to carry out a lunar mission, particularly rendezvousing and docking two objects in space, the United States in late 1961 decided to develop a two-person spacecraft called Gemini. The Gemini spacecraft was much more complex than the rudimentary Mercury capsule and, at 3.81 metric tons, was twice as heavy. Another converted air force ICBM, a Titan (Titan rocket) II, was used to launch the Gemini spacecraft.

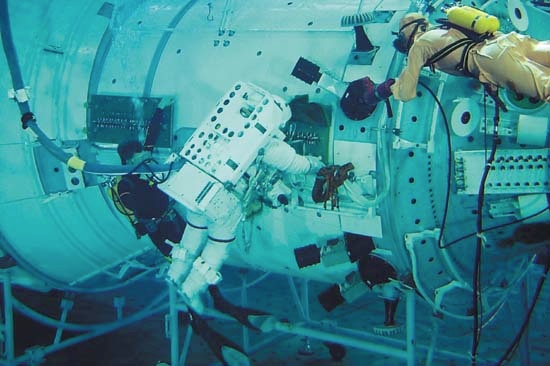

The first manned Gemini mission lifted into space in March 1965; nine more missions followed, the last in November 1966. On the second mission in June 1965, Edward H. White II (White, Edward H., II) became the first American astronaut to operate outside a spacecraft. His 20-minute space walk—also known as extravehicular activity (EVA)—was without incident. Although problems developed on many of the Gemini flights, the program demonstrated that people could live and work in space for as long as 14 days, more than the time needed for a round trip to the Moon. It also showed that astronauts could carry out rendezvous in space and could make useful observations of Earth, both visually and photographically.

As plans in the United States for multiple-astronaut missions became known, the Soviet Union worked to maintain its lead in the space race by modifying the Vostok spacecraft so that it could carry as many as three persons. Korolyov could accomplish this only by having the crew fly without wearing spacesuits. The redesigned spacecraft was known as Voskhod. There were two Voskhod missions, one with three people aboard in October 1964 and another with a two-man crew in March 1965. On the second mission, cosmonaut Aleksey Leonov (Leonov, Aleksey Arkhipovich) became the first human to leave an orbiting spacecraft, less than three months before White. His 12-minute EVA was full of problems, and his reentry of the Voskhod spacecraft was particularly difficult.

Soyuz

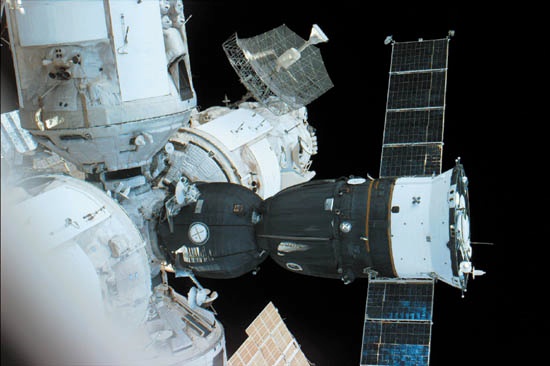

Korolyov and his associates began work in 1962 on a second-generation spacecraft, to be called Soyuz. It was to be a much more complex vehicle than Vostok, holding as many as three people in an orbital crew compartment, with a separate module for crew reentry and a third section containing spacecraft equipment and rocket engines for in-orbit and reentry maneuvers. Soyuz was to be capable not only of flights in Earth orbit but also, in modified versions, of flights around the Moon and even a lunar landing.

Korolyov and his associates began work in 1962 on a second-generation spacecraft, to be called Soyuz. It was to be a much more complex vehicle than Vostok, holding as many as three people in an orbital crew compartment, with a separate module for crew reentry and a third section containing spacecraft equipment and rocket engines for in-orbit and reentry maneuvers. Soyuz was to be capable not only of flights in Earth orbit but also, in modified versions, of flights around the Moon and even a lunar landing.The first launch of Soyuz, with a single cosmonaut, Vladimir Komarov (Komarov, Vladimir Mikhaylovich), aboard, took place on April 23, 1967. Once the spacecraft reached orbit, it suffered a number of problems, which prompted ground controllers to bring Komarov back to Earth as soon as possible. After reentry, however, the spacecraft's main parachute did not fully deploy, and the Soyuz hit the ground at high speed. Komarov became the first person to perish during a spaceflight, and the accident dealt a major blow to Soviet hopes of orbiting or landing on the Moon before the United States.

After the problems with the Soyuz design were diagnosed and remedied, various models of the spacecraft served as the means of access to space for the Soviet, and then Russian, program of human spaceflight for more than 30 years. At the start of the 21st century, a version of Soyuz was used as the crew rescue vehicle—the lifeboat—for the early phase of construction and occupancy of the International Space Station.

The race to the Moon

The American commitment

In the immediate aftermath of Gagarin's orbital flight, President Kennedy was advised by his vice president, Lyndon B. Johnson, of Braun's belief that the Soviet Union, using Korolyov's existing R-7 launcher, could well succeed in sending a multiperson spacecraft into Earth orbit and perhaps even around the Moon before the United States. The first competition that the United States had a good chance of winning would be that of a manned lunar landing, because it would require each country to develop a new, more powerful rocket. On those technical grounds and because a lunar landing would be a very visible demonstration of American strength, Kennedy announced on May 25, 1961, that the United States would commit itself to a lunar landing before 1970. At that time, only one American human spaceflight, Shepard's 15-minute suborbital journey, had been made.

In response to Kennedy's decision, the United States carried out a warlike, but peaceful, mobilization of financial and human resources. NASA's budget was increased almost 500 percent in three years, and at its peak the lunar landing program involved more than 34,000 NASA employees and 375,000 employees of industrial and university contractors.

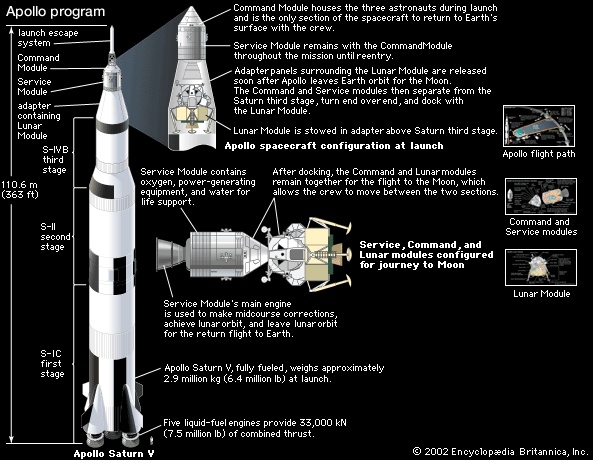

By the end of 1962, the basic elements of what was called Project Apollo (Apollo program) were in place. The launch vehicle would be a powerful Saturn V rocket, 110.6 metres (363 feet) tall and power-driven by five huge engines generating a total of 33,000 kilonewtons (7.5 million pounds) of lifting power at takeoff—100 times the takeoff thrust of the Redstone rocket that had launched Shepard. After an intense debate, NASA chose a spacecraft configuration for Apollo that could be sent up in one launch, rather than a larger spacecraft that would need to be assembled in a series of rendezvous in Earth orbit. The Apollo spacecraft would have three sections. A Command Module would house the three-person crew on liftoff and landing and during the trip to and from the Moon. A Service Module would carry various equipment and the rocket engine needed to guide the spacecraft into lunar orbit and then send it back to Earth. A Lunar Module, comprising a descent stage and an ascent stage, would carry two people from lunar orbit to the Moon's surface and back to the Command Module. The ability of the Lunar Module's ascent stage to rendezvous and dock in lunar orbit with the Command Module after takeoff from the Moon was critical to the success of the mission. NASA also created a large new launch facility on Merritt Island, near Cape Canaveral (Canaveral, Cape), Florida, as the Apollo spaceport.

By the end of 1962, the basic elements of what was called Project Apollo (Apollo program) were in place. The launch vehicle would be a powerful Saturn V rocket, 110.6 metres (363 feet) tall and power-driven by five huge engines generating a total of 33,000 kilonewtons (7.5 million pounds) of lifting power at takeoff—100 times the takeoff thrust of the Redstone rocket that had launched Shepard. After an intense debate, NASA chose a spacecraft configuration for Apollo that could be sent up in one launch, rather than a larger spacecraft that would need to be assembled in a series of rendezvous in Earth orbit. The Apollo spacecraft would have three sections. A Command Module would house the three-person crew on liftoff and landing and during the trip to and from the Moon. A Service Module would carry various equipment and the rocket engine needed to guide the spacecraft into lunar orbit and then send it back to Earth. A Lunar Module, comprising a descent stage and an ascent stage, would carry two people from lunar orbit to the Moon's surface and back to the Command Module. The ability of the Lunar Module's ascent stage to rendezvous and dock in lunar orbit with the Command Module after takeoff from the Moon was critical to the success of the mission. NASA also created a large new launch facility on Merritt Island, near Cape Canaveral (Canaveral, Cape), Florida, as the Apollo spaceport.The Soviet response

While committing the United States to winning the Moon race, President Kennedy also made several attempts in the early 1960s to convince the Soviet leadership that a cooperative lunar landing program between their two countries would be a better alternative. No positive reply from the Soviet Union was forthcoming, however. In fact, between 1961 and 1963, there was still vigorous debate within the Soviet Union over the wisdom of undertaking a lunar program, and no final decision had been made on the question.

Meanwhile, the separate design bureaus headed by Korolyov and his rival Vladimir Chelomey (Chelomey, Vladimir Nikolayevich) competed fiercely for a lunar mission assignment, either a flight around the Moon or an actual landing. Finally, in August 1964, Korolyov received the lunar landing assignment, and soon afterward Chelomey was given responsibility for planning a circumlunar flight to be carried out before the 50th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution, which would take place in October 1967. In 1965 Soviet leaders decided to combine the efforts of the two rivals for the circumlunar mission, using a version of Korolyov's Soyuz spacecraft and a new rocket, the UR-500 (also called the Proton), designed by Chelomey.

The rocket that Korolyov designed for the lunar landing effort was called the N1. Like the Saturn V, it was huge, standing 112.8 metres (370 feet) tall and having a planned takeoff thrust of 44,500 kilonewtons (10 million pounds). Instead of a few large rocket engines in its first stage, however, the N1 had 30 smaller engines. These were developed by Nikolay Kuznetsov, an aircraft-engine chief designer who had little experience with rocket engines, rather than the more capable Glushko. Korolyov and Glushko, already personal adversaries for many years, had disagreed on the proper fuel for the N1, and they finally decided that they could no longer work together. Consequently, Korolyov turned to Kuznetsov, who chose the small-engine approach.

Indecision, inefficiencies, inadequate budgets, and personal and organizational rivalries in the Soviet system thus posed major obstacles to success in the race to the Moon. To these was added the unexpected death of Korolyov, age 59, during surgery on January 14, 1966. This was a serious setback to the Soviet space program. Korolyov had been a charismatic leader and organizer. His successor, Vasily Mishin, attempted to maintain the program's momentum, but he was not the effective manager or politically sophisticated operator that Korolyov had been.

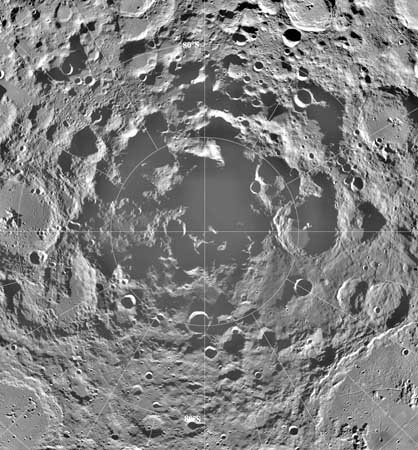

Interim developments

In the United States, Apollo moved forward as a high-priority program. A major setback occurred on January 27, 1967, when astronauts Grissom, White, and Roger Chaffee (Chaffee, Roger B.) were killed after their Apollo 1 Command Module caught fire during a ground test. The first manned Apollo mission, designated Apollo 7 and intended to test the redesigned Command Module, was launched into Earth orbit on October 11, 1968. The launcher used was a Saturn IB, a less-powerful rocket than the Saturn V needed to reach the Moon. The mission's success cleared the way for a bold step—the first launch of a crew atop a Saturn V to the lunar vicinity. On December 21, 1968, the Apollo 8 Command and Service modules were put on a trajectory that sent them into orbit around the Moon on Christmas Eve, December 24. The three astronauts—Frank Borman (Borman, Frank), James A. Lovell, Jr. (Lovell, James A(rthur), Jr.), and William A. Anders (Anders, William A.)—sent back close-up images of the lunar surface, read from the biblical book of Genesis, and brought back vivid colour photographs of a blue planet Earth rising over the desolate lunar landscape. By the end of the mission, it was clear that the first lunar landing was only months away.