David, Jacques-Louis

French painter

Introduction

born Aug. 30, 1748, Paris

died Dec. 29, 1825, Brussels

the most celebrated French artist of his day and a principal exponent of the late 18th-century Neoclassical reaction against the Rococo style.

the most celebrated French artist of his day and a principal exponent of the late 18th-century Neoclassical reaction against the Rococo style. David won wide acclaim with his huge canvases on classical themes (e.g., Oath of the Horatii, 1784). When the French Revolution began in 1789, he served briefly as its artistic director and painted its leaders and martyrs (The Death of Marat, 1793) in a style that is more realistic than classical. Later he was appointed painter to Napoleon. Although primarily a painter of historical events, David was also a great portraitist (e.g., Portrait of Mme Récamier, 1800).

David won wide acclaim with his huge canvases on classical themes (e.g., Oath of the Horatii, 1784). When the French Revolution began in 1789, he served briefly as its artistic director and painted its leaders and martyrs (The Death of Marat, 1793) in a style that is more realistic than classical. Later he was appointed painter to Napoleon. Although primarily a painter of historical events, David was also a great portraitist (e.g., Portrait of Mme Récamier, 1800).Formative years

David was born in the year when new excavations at the ash-buried ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum were beginning to encourage a stylistic return to antiquity (without being, as was long supposed, a principal cause of that return). His father, a small but prosperous dealer in textiles, was killed in a duel in 1757, and the boy was subsequently raised, reportedly not very tenderly, by two uncles. After classical literary studies and a course in drawing, he was placed in the studio of Joseph-Marie Vien, a history painter who catered to the growing Greco-Roman taste without quite abandoning the light sentiment and the eroticism that had been fashionable earlier in the century. At age 18, the obviously gifted budding artist was enrolled in the school of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. After four failures in the official competitions and years of discouragement that included an attempt at suicide (by the stoic method of avoiding food), he finally obtained, in 1774, the Prix de Rome, a government scholarship that not only provided a stay in Italy but practically guaranteed lucrative commissions in France. His prize-winning work, Antiochus and Stratonice, reveals that at this point he could still be influenced slightly by the Rococo charm of the painter François Boucher (Boucher, François), who had been a family friend.

In Italy there were many influences, including those of the dark-toned 17th-century Bolognese school, the serenely classical Nicolas Poussin (Poussin, Nicolas), and the dramatically realistic Caravaggio. David absorbed all three, with an evident preference for the strong light and shade of the followers of Caravaggio. For a while he seemed determined to fulfill a prediction he had made on leaving France: “The art of antiquity will not seduce me, for it lacks liveliness . . . .” But he became interested in the Neoclassical doctrines that had been developed in Rome by, among others, the German painter Anton Raphael Mengs (Mengs, Anton Raphael) and the art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann (Winckelmann, Johann). In the company of Quatremère de Quincy, a young French sculptor who was a strong partisan of the return to antiquity, he visited the ruins of Herculaneum, the Doric temples at Paestum, and the Pompeian collections at Naples. In front of the ancient vases and columns, he felt, he said later, that he had just been “operated on for cataract of the eye.”

Rise to fame: 1780–94

Back in Paris in 1780, he completed and successfully exhibited Belisarius Asking Alms, in which he combined a nobly sentimental approach to antiquity with a pictorial technique reminiscent of Poussin. In 1782 he married the spirited Marguerite Pécoul, whose father was a wealthy building contractor and the superintendent of construction at the Louvre—a position that carried considerable influence. From this date David prospered rapidly.

The pathos and painterly skill of Andromache Mourning Hector brought him election to the Académie Royale in 1784; and that same year, accompanied this time by his wife and studio assistants, he returned to Rome with a commission to complete a painting that appears to have been originally inspired by a Paris performance of Pierre Corneille (Corneille, Pierre)'s Horace. The result, finally not based on any of the incidents in the play, was the Oath of the Horatii. The subject is the solemn moment, charged with stoicism and simple courage, when the three Horatii brothers face their father and offer their lives to assure victory for Rome in the war with Alba; the pictorial treatment—firm contours, bare cubic space, sober colour, frieze-like composition, and clear lighting—is as austerely non-Rococo as the subject. Exhibited first in David's studio in Rome and then, following his return to France, in the official Paris Salon of 1785, the picture created a sensation; it was regarded as a manifesto for an artistic revival (the term Neoclassicism was not yet in use) that would cure Europe of the lingering addiction to dainty curves and boudoir themes. Eventually, it came to be regarded, although such was almost certainly not the first intention, as a manifesto for an end to the corruption of an effete aristocracy and for a return to the stern, patriotic morals attributed to republican Rome.

The pathos and painterly skill of Andromache Mourning Hector brought him election to the Académie Royale in 1784; and that same year, accompanied this time by his wife and studio assistants, he returned to Rome with a commission to complete a painting that appears to have been originally inspired by a Paris performance of Pierre Corneille (Corneille, Pierre)'s Horace. The result, finally not based on any of the incidents in the play, was the Oath of the Horatii. The subject is the solemn moment, charged with stoicism and simple courage, when the three Horatii brothers face their father and offer their lives to assure victory for Rome in the war with Alba; the pictorial treatment—firm contours, bare cubic space, sober colour, frieze-like composition, and clear lighting—is as austerely non-Rococo as the subject. Exhibited first in David's studio in Rome and then, following his return to France, in the official Paris Salon of 1785, the picture created a sensation; it was regarded as a manifesto for an artistic revival (the term Neoclassicism was not yet in use) that would cure Europe of the lingering addiction to dainty curves and boudoir themes. Eventually, it came to be regarded, although such was almost certainly not the first intention, as a manifesto for an end to the corruption of an effete aristocracy and for a return to the stern, patriotic morals attributed to republican Rome.David became a culture hero; he was even referred to in some quarters as a messiah. He added to his fame by producing in 1787 the morally uplifting Death of Socrates, in 1788 the less uplifting but archaeologically interesting Paris and Helen, and in 1789 another lesson in self-sacrifice, The Lictors Bringing to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons. By the time the Brutus was on view, the French Revolution had begun, and this picture of the patriotic Roman consul who condemned his traitorous sons to death had an unanticipated political significance. It also had, through its presumably accurate reconstitution of the details of everyday Roman life, an effect that was perhaps equally unexpected, for with it David began the long and extensive influence he was to have on French fashions. Up-to-date homes began to display imitations of his Roman furniture; men cut their hair short in the Roman style; and women adopted the dresses and the coiffures of Brutus' daughters. Later on, even the flimsy Sabine dress, which left the breasts exposed, was adopted by the ultramodern.

In the early years of the Revolution, David was a member of the extremist Jacobin group led by Robespierre (Robespierre, Maximilien de), and he became an energetic example of the politically committed artist. He was elected to the National Convention in 1792, in time to vote for the execution of Louis XVI. By 1793, as a member of the art commission, he was virtually the art dictator of France and was nicknamed “the Robespierre of the brush.” He preached moral and aesthetic sermons to the Convention:

The artist must be a philosopher. Socrates the skilled sculptor, Jean-Jacques 【Rousseau】 the good musician, and the immortal Poussin, tracing on the canvas the sublime lessons of philosophy, are so many proofs that an artistic genius should have no other guide except the torch of reason.

Guided supposedly by the torch of reason and perhaps also by bitter memories of his many unsuccessful attempts to win the Prix de Rome, he succeeded in abolishing the Académie Royale and with it much of the old regime's system for training artists and providing them with patronage. The Académie was replaced briefly by a body called the Commune des Arts, then by a group called the Popular and Republican Society of the Arts, and then, finally, in 1795, after David was out of power, by the beginning of the system—a combination of the Institut de France and the École des Beaux-Arts—that dominated French artistic life during most of the 19th century.

As an artist during these years of his dictatorship, David was frequently busy with revolutionary propaganda. He had commemorative medals struck, set up obelisks in the provinces, and staged national festivals and the grandiose funerals the new government gave its martyrs. Some of his projects for paintings at this time were never completely carried out: one of these is the unfinished Joseph Bara, which is a tribute to a drummer boy shot by the royalists, and another is the sketched Oath of the Tennis Court, which was to commemorate the moment in 1789 when the Third Estate (the commoners) swore not to disband until a new constitution had been adopted. The Death of Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau, painted to honour a murdered deputy and regarded by David as one of his best pictures, was eventually destroyed. The result of all this is that the artist's Jacobin inspiration is represented principally by The Death of Marat, painted in 1793 shortly after the murder of the revolutionary leader by Charlotte Corday (Corday, Charlotte). This “pietà of the Revolution,” as it has been called, is generally considered David's masterpiece and an example of how, under the pressure of genuine emotion, Neoclassicism could turn into tragic Realism.

As an artist during these years of his dictatorship, David was frequently busy with revolutionary propaganda. He had commemorative medals struck, set up obelisks in the provinces, and staged national festivals and the grandiose funerals the new government gave its martyrs. Some of his projects for paintings at this time were never completely carried out: one of these is the unfinished Joseph Bara, which is a tribute to a drummer boy shot by the royalists, and another is the sketched Oath of the Tennis Court, which was to commemorate the moment in 1789 when the Third Estate (the commoners) swore not to disband until a new constitution had been adopted. The Death of Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau, painted to honour a murdered deputy and regarded by David as one of his best pictures, was eventually destroyed. The result of all this is that the artist's Jacobin inspiration is represented principally by The Death of Marat, painted in 1793 shortly after the murder of the revolutionary leader by Charlotte Corday (Corday, Charlotte). This “pietà of the Revolution,” as it has been called, is generally considered David's masterpiece and an example of how, under the pressure of genuine emotion, Neoclassicism could turn into tragic Realism.Later years: 1794–1825

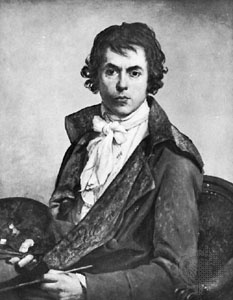

In 1794, after his friend Robespierre had been sent to the guillotine, David was arrested. At his trial he is said to have defended himself badly, mumbling that in the future he intended to attach himself “to principles and not to men.” He was imprisoned twice, for four months in 1794 and for two more the next year, apparently most of the time in the not uncomfortable Palais du Luxembourg in Paris. He was consoled by being allowed to paint and also by the fact that his wife, who had divorced him two years earlier for having voted for the death of the King, now loyally returned in his hour of trouble and remarried him, on this occasion for good. During his first period in prison, he painted from his window his only landscape, the View of the Luxembourg Gardens. While he was held temporarily in another Paris building, he did an unfinished self-portrait. At 46 he appears as a boyish young man with romantically disheveled hair, brown eyes, and a generally aggressive, if worried, look; a cheek tumour from which he suffered all of his adult life and which is said to have impeded his speech gives his face a slight twist.

Even during his imprisonment, he had retained three studios in the Louvre, and, after the amnesty of 1795, he devoted to teaching the same energy he had been devoting to revolutionary politics. Eventually, in the interval between his painting of Oath of the Horatii and Napoleon's defeat at the Battle of Waterloo, he was responsible for the training and indoctrination of hundreds of young painters from all over Europe, among them such future masters as François Gérard (Gérard, François, Baron), Antoine-Jean Gros (Gros, Antoine-Jean, Baron), and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (Ingres, J.-A.-D). The indoctrination began with the premise that the basis of art was the contour, and so it can be held partly responsible for the excessive emphasis on drawing that characterized European academic painting in the 19th century. But David himself, as his works show, was not always hostile to rich chromatic effects; as late as 1860 he could be called, by no less a colourist than Eugène Delacroix (Delacroix, Eugène), “the father of the whole modern school.”

Neoclassicism was presumably inclined to scorn portraiture, because a contemporary sitter would normally lack both the universality and the nudity of an ancient statue. David, however, had done portraits, remarkable for their psychological individuality and their look of solid flesh, since the beginning of his career: in 1782–83 his sitter had been Alphonse Leroy, a Paris medical professor; in 1784 Mme Pécoul, his mother-in-law; in 1788 the chemist Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier, with Mme Lavoisier. In 1795 the freed artist portrayed his pretty, elegant sister-in-law, Mme Sériziat, and her dandyish husband. In 1800 he produced his famous period piece, Portrait of Mme Récamier, which he left unfinished because the sitter, then at the start of her career as a reigning Paris beauty, proved unreliable about hours for posing.

Neoclassicism was presumably inclined to scorn portraiture, because a contemporary sitter would normally lack both the universality and the nudity of an ancient statue. David, however, had done portraits, remarkable for their psychological individuality and their look of solid flesh, since the beginning of his career: in 1782–83 his sitter had been Alphonse Leroy, a Paris medical professor; in 1784 Mme Pécoul, his mother-in-law; in 1788 the chemist Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier, with Mme Lavoisier. In 1795 the freed artist portrayed his pretty, elegant sister-in-law, Mme Sériziat, and her dandyish husband. In 1800 he produced his famous period piece, Portrait of Mme Récamier, which he left unfinished because the sitter, then at the start of her career as a reigning Paris beauty, proved unreliable about hours for posing.But David was not a man for the life of a mere teacher and portraitist. In 1799 he made a spectacular reentry into public notice with a new giant canvas, The Intervention of the Sabine Women. The picture, often mistakenly referred to as The Rape of the Sabines, represents the moment, a few years after the legendary abduction, when the women, now contented wives and mothers, halt a battle between their Roman husbands and the Sabine men who have come on an unwanted rescue mission; in the middle of the melee stands the lovely Sabine woman Hersilia, appealing with one arm toward the Roman Romulus and the other toward the bearded Sabine Tatius. The artist had said that his aim was to move away from the allegedly crude Roman manner of the Oath of the Horatii into a more graceful Greek manner, and he did win enthusiastic applause for the elegance of his figures. He also won some approval for his supposed intention to preach conciliation after 10 years of bloodletting in France. But he attracted perhaps the most attention with the nakedness of his ancient warriors; having ceased to be the Robespierre of the brush, he now became, in a popular jingle, “the Raphael of the sansculottes (sansculotte)” (i.e., the Raphael of the radical Republicans).

Napoleon (Napoleon I) admired The Intervention of the Sabine Women and saw possibilities for self-aggrandizement in the talent displayed. Soon David, without acquiring political office, was again a government painter, first under the Consulate and then, after 1804, under the Empire. He was not, however, the only prominent Frenchman to move from the Jacobin left to the Bonapartist right, and he had evidently always been a worshiper of historical heroes. His most important Napoleonic work is the huge Coronation of Napoleon in Notre-Dame (1805–07), sometimes called Napoleon Crowning the Empress Josephine; in it Neoclassicism gives way to a style that combines the official portraiture of the old French monarchy with overtones—and occasional straight imitation—of the masters of the Italian Renaissance. This picture was followed in 1810 by the large Napoleon Distributing the Eagles and in 1812 by The Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries, a sharply perceptive portrait notwithstanding its conspicuously propagandistic intention.

Napoleon (Napoleon I) admired The Intervention of the Sabine Women and saw possibilities for self-aggrandizement in the talent displayed. Soon David, without acquiring political office, was again a government painter, first under the Consulate and then, after 1804, under the Empire. He was not, however, the only prominent Frenchman to move from the Jacobin left to the Bonapartist right, and he had evidently always been a worshiper of historical heroes. His most important Napoleonic work is the huge Coronation of Napoleon in Notre-Dame (1805–07), sometimes called Napoleon Crowning the Empress Josephine; in it Neoclassicism gives way to a style that combines the official portraiture of the old French monarchy with overtones—and occasional straight imitation—of the masters of the Italian Renaissance. This picture was followed in 1810 by the large Napoleon Distributing the Eagles and in 1812 by The Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries, a sharply perceptive portrait notwithstanding its conspicuously propagandistic intention.After the fall of Napoleon in 1815, David was exiled to Brussels. Cut off from the excitement and stimulus of the great events he had lived through, he lost much of his old energy. Toward the end of his life, he executed, probably with considerable help from a Belgian pupil, François-Joseph Navez, one more remarkably convincing portrait: The Three Women of Ghent.

Additional Reading

E.J. Delécluze, Louis David, son école et son temps (1855, reprinted 1983), is a primary source of information by one of the artist's pupils. Biographies include David Lloyd Dowd, Pageant-Master of the Republic: Jacques-Louis David and the French Revolution (1948, reissued 1969); Simon Lee, David (1999); and Antonio Pinelli, David (2004). General histories of style containing perceptive analyses of David's work are Walter Friedlaender, David to Delacroix (1952, reissued 1980; originally published in German, 1930); Robert Rosenblum, Transformations in Late Eighteenth Century Art (1967); Hugh Honour, Neo-Classicism (1968, reissued 1991); and Anita Brookner, Jacques-Louis David (1980). Philippe Bordes, Jacques-Louis David: Empire to Exile (2005), is an exhibition catalogue.

- Alain de Lille

- Alain-Fournier

- Alain Grandbois

- Alain Locke

- Alain-René Lesage

- Alain Resnais

- Alain Robbe-Grillet

- Alajuela

- al- Akhṭal

- Alakol, Lake

- Alalakh

- Alameda

- Alamein, El-

- Alamo

- Alamogordo

- Alamosa

- Alamán, Lucas

- al- Amīn

- Alan Baker

- Alanbrooke, Alan Francis Brooke, 1st Viscount, Baron Alanbrooke of Brookeborough

- Alan B. Shepard, Jr.

- Alan Dugan

- Alan Fisher

- Alan García

- Alan Garner