Hong Kong

administrative region, China

Introduction

Chinese (Pinyin) Xianggang or (Wade-Giles) Hsiang-Kang

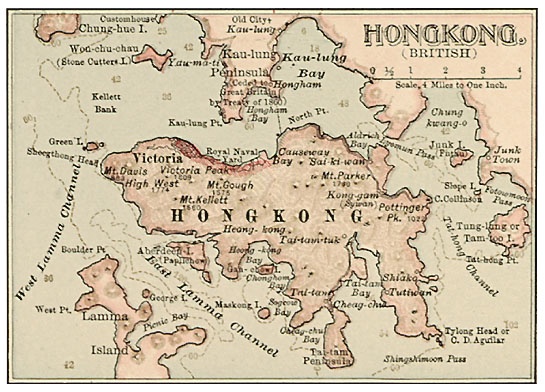

Hong Kong, flag ofspecial administrative region (Pinyin: tebie xingzhengqu; Wade-Giles: t'e-pieh hsing-cheng-ch'ü) of China located to the east of the Pearl River (Xu Jiang) estuary on the south coast of China. The region is bordered by Guangdong province on the north and the South China Sea on the east, south, and west. It consists of Hong Kong Island, originally ceded by China to Great Britain (British Empire) in 1842, the southern part of the Kowloon Peninsula and Stonecutters (Ngong Shuen) Island (now joined to the mainland), ceded in 1860, and the New Territories, which include the mainland area lying largely to the north, together with 230 large and small offshore islands—all of which were leased from China for 99 years from 1898 to 1997. The Chinese-British joint declaration signed on Dec. 19, 1984, paved the way for the entire territory to be returned to China, which occurred July 1, 1997.

Hong Kong, flag ofspecial administrative region (Pinyin: tebie xingzhengqu; Wade-Giles: t'e-pieh hsing-cheng-ch'ü) of China located to the east of the Pearl River (Xu Jiang) estuary on the south coast of China. The region is bordered by Guangdong province on the north and the South China Sea on the east, south, and west. It consists of Hong Kong Island, originally ceded by China to Great Britain (British Empire) in 1842, the southern part of the Kowloon Peninsula and Stonecutters (Ngong Shuen) Island (now joined to the mainland), ceded in 1860, and the New Territories, which include the mainland area lying largely to the north, together with 230 large and small offshore islands—all of which were leased from China for 99 years from 1898 to 1997. The Chinese-British joint declaration signed on Dec. 19, 1984, paved the way for the entire territory to be returned to China, which occurred July 1, 1997. Hong Kong's area has expanded over the years, and it continues to grow as more land is reclaimed from the surrounding sea. Hong Kong Island and its adjacent islets have an area of only about 31 square miles (81 square km), while urban Kowloon, which includes the Kowloon Peninsula south of Boundary Street, and Stonecutters Island measure about 18 square miles (47 square km). The New Territories account for the rest of the area—more than 90 percent of the total. The Victoria urban district located on the barren rocks of the northwestern coast of Hong Kong Island is the place where the British first landed in 1841, and it has since been the centre of administrative and economic activities.

Hong Kong's area has expanded over the years, and it continues to grow as more land is reclaimed from the surrounding sea. Hong Kong Island and its adjacent islets have an area of only about 31 square miles (81 square km), while urban Kowloon, which includes the Kowloon Peninsula south of Boundary Street, and Stonecutters Island measure about 18 square miles (47 square km). The New Territories account for the rest of the area—more than 90 percent of the total. The Victoria urban district located on the barren rocks of the northwestern coast of Hong Kong Island is the place where the British first landed in 1841, and it has since been the centre of administrative and economic activities. Hong Kong developed initially on the basis of its excellent natural harbour (its Chinese name means “fragrant harbour”) and the lucrative China trade, particularly opium dealing. It was the expansion of its territory, however, that provided labour and other resources necessary for sustained commercial growth that led to its becoming one of the world's major trade and financial centres. The community remains limited in space and natural resources, and it faces persistent problems of overcrowding, trade fluctuations, and social and political unrest. Nevertheless, Hong Kong has emerged strong and prosperous, albeit with a changed role, as an entrepôt, a manufacturing and financial centre, and a vital agent in the trade and modernization of China.

Hong Kong developed initially on the basis of its excellent natural harbour (its Chinese name means “fragrant harbour”) and the lucrative China trade, particularly opium dealing. It was the expansion of its territory, however, that provided labour and other resources necessary for sustained commercial growth that led to its becoming one of the world's major trade and financial centres. The community remains limited in space and natural resources, and it faces persistent problems of overcrowding, trade fluctuations, and social and political unrest. Nevertheless, Hong Kong has emerged strong and prosperous, albeit with a changed role, as an entrepôt, a manufacturing and financial centre, and a vital agent in the trade and modernization of China.Physical and human geography (Hong Kong)

The land

Relief

In sharp contrast to the low-lying areas of the Pearl River delta but conforming geologically and structurally to the great South China massif, a well-eroded upland region, Hong Kong has rugged relief and marked variations in topography. Structurally, the area is an anticline, running northeast-southwest, that was formed toward the latter part of the Jurassic Period (about 150 million years ago). Lava poured into this structure and formed volcanic rocks that were later intruded by an extensive granitic dome. The harbour of Hong Kong was formed by the drowning of the denuded centre of the dome. The surrounding hills on the mainland and on Hong Kong Island are partly capped by volcanic rocks, and steep, scarplike concave slopes lead to the inner harbour.

In sharp contrast to the low-lying areas of the Pearl River delta but conforming geologically and structurally to the great South China massif, a well-eroded upland region, Hong Kong has rugged relief and marked variations in topography. Structurally, the area is an anticline, running northeast-southwest, that was formed toward the latter part of the Jurassic Period (about 150 million years ago). Lava poured into this structure and formed volcanic rocks that were later intruded by an extensive granitic dome. The harbour of Hong Kong was formed by the drowning of the denuded centre of the dome. The surrounding hills on the mainland and on Hong Kong Island are partly capped by volcanic rocks, and steep, scarplike concave slopes lead to the inner harbour.The area is a partially submerged, dissected upland terrain that rises abruptly to heights of more than 2,950 feet (900 metres); its backbone is made up of a series of ridges, running northeast to southwest, that tie in closely with the structural trend in South China. This trend is clearly observable from the alignment of Lantau Island and the Tolo Channel. From Mount Tai Mo—at 3,140 feet (957 metres) the highest peak in the territory—the series of ridges extends southwestward to Lantau Island (Lantao Island), where the terrain rises to 3,064 feet on Lantau Peak and 2,851 feet on Sunset Peak. Extending southeastward from Mount Tai Mo, the Kowloon Peak attains an elevation of 1,975 feet, but there is an abrupt drop to about 650 feet at Devil's Peak. Victoria (Hong Kong) Harbour is well protected by mountains on Hong Kong Island that include Victoria Peak in the west, which rises to 1,810 feet, and Mount Parker in the east, which reaches a height of about 1,742 feet.

Lowlands of the Hong Kong region, including floodplains, river valleys, and reclaimed land, occupy less than one-fifth of the land. Extensive lowland regions are found only north of Mount Tai Mo, in the Yuen Long and Sheung Shui plains. The urban area that spans the two sides of the harbour, with continued reclamation, takes up only about one-tenth of the level area.

Drainage

Hong Kong lacks a river system of any scope, the only exception being in the north where the Sham Chun River, which forms the boundary between Guangdong and Hong Kong, flows into Deep Bay after collecting a number of small tributaries. Most of the streams are small, and they generally run perpendicular to the northeast-southwest trend of the terrain. The construction of reservoirs and their catchment systems has reduced the amount of fresh water available downstream.

Soils

In general, Hong Kong's soils are acidic and of low fertility. An exception is the alluvial soils, which are found mainly in the Deep Bay area, where the sediment-laden waters of the Pearl meet saline waters at high tide and slow down to deposit their sediments to form mud flats. Paddy rice farming and, more recently, intensive vegetable cultivation have modified the alluvial soils. Elsewhere, hill soils, classified as red-yellow podzolic and krasnozem, abound. Under forest, these hill soils have a well-developed profile, with rich topsoil, but, when they are exposed, as is mostly the case, they tend to be thin and lacking in nutrients. Under tropical conditions, sheet and gully erosion is extensive and drastic.

Climate

Hong Kong lies at the northern fringe of the tropical zone. Its seasonal changes are well marked, however, with hot, humid summers and cool, dry winters. The climate is largely controlled by the pressure systems over the adjacent great Asian landmass and ocean surface. Thus, monsoonal winds blow from the northeast in winter as a result of the cooling of the landmass and the development of a large thermal anticyclone over Inner Mongolia. Southeast winds develop in summer when the North Pacific Ocean heats up more slowly through solar radiation and becomes a high-pressure area.

The mean January and July temperatures are about 60 °F (16 °C) and 84 °F (29 °C), respectively. The lowest recorded temperature was 32 °F (0 °C) in January 1893, and the highest was 97 °F (36 °C) in August 1900. Frost occasionally occurs on hilltops in winter. The average annual rainfall amounts to about 88 inches (2,220 millimetres), more than half of which falls during the summer months of June, July, and August; only about 10 percent falls from November to March. Tropical cyclones, or typhoons, generally occur between June and October, and, of the 20 to 30 typhoons formed over the western North Pacific and South China Sea each year, an average of five or six may affect Hong Kong. The torrential downpours and strong winds that frequently accompany the typhoons sometimes devastate life and property in Hong Kong and adjacent areas of Guangdong.

Plant and animal life

Hong Kong is noted for the lushness and great diversity of its plant life. The transitional climate between humid subtropical and warm temperate maritime excludes the most sensitive humid tropical genera due to the cool, dry winter conditions, but many tropical as well as temperate-zone families are represented. Most of the land, except for the heavily eroded badlands, is under tropical herbaceous growth, including mangrove and other swamp cover. The most common forest genus today is Pinus, represented by the native South China red pine and the slash pine, introduced from Australia. Some of the oldest areas of woodland are in the feng-shui wood, or “sacred groves,” found in many New Territories villages. These woods consist essentially of native forest trees, some of which are of potential value to the villagers. Centuries of cutting and burning, however, have destroyed much of Hong Kong's original vegetation, leaving only about one-eighth of the land forested. A large portion of Hong Kong's present-day forest cover owes its origin to postwar afforestation programs, which have restored some of the stands of pine, eucalyptus, banyan, casuarina, and palm trees.

Hong Kong's animal life consists of a mixture of mammals adapted to the subtropical environment. Among the few arboreal mammals are two species of nonnative monkeys that flourish in forests of the New Territories, the rhesus macaque and the long-tailed macaque. Tigers are reputed to have once roamed the area, but they are no longer in evidence. The largest remaining carnivores are rare and include the South China red fox, the Chinese leopard cat, the seven-banded civet, and the masked palm civet. Some rat and mouse species typically inhabit scrubland and grassland areas. Birdlife is abundant, and there are numerous species of snakes, lizards, and frogs.

Settlement patterns

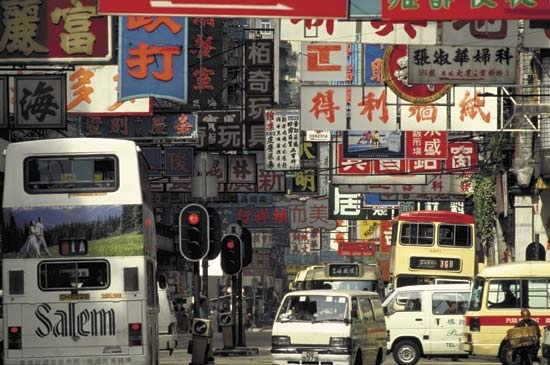

The predominantly urban settlements of Hong Kong are typically distributed linearly, following the irregular coastline and transportation routes. The principal urban areas are established on Hong Kong Island and the Kowloon Peninsula, where more than half of the total population lives. There, most of the population is concentrated around Victoria Harbour, living on the limited flatland that is being continuously extended by reclamation. Many major streets, especially those on the northern shore of Hong Kong Island, as well as the entire industrial district of Kwun Tong and the eastern portion of Tsim Sha Tsui at the tip of the peninsula, have been built on reclaimed land.

The predominantly urban settlements of Hong Kong are typically distributed linearly, following the irregular coastline and transportation routes. The principal urban areas are established on Hong Kong Island and the Kowloon Peninsula, where more than half of the total population lives. There, most of the population is concentrated around Victoria Harbour, living on the limited flatland that is being continuously extended by reclamation. Many major streets, especially those on the northern shore of Hong Kong Island, as well as the entire industrial district of Kwun Tong and the eastern portion of Tsim Sha Tsui at the tip of the peninsula, have been built on reclaimed land.In the New Territories north of the Kowloon hills, rural settlements vary from hamlets to small towns. Most of the villages, compactly built and often walled, follow the alignment of the river systems in the low-lying but fertile alluvial floodplains or the major route corridors. Villages of the Cantonese people are located mainly in the flat alluvial regions, whereas villages of the Hakka people usually are found in narrow valleys or on foothills. The feng-shui grove and pond are characteristic of both the Cantonese and Hakka villages; the grove is generally planted on the upslope, or back side, of a village for shade and protection, and the pond is for fish-farming.

A number of new towns have sprung up in the New Territories as a result of the tremendous increase in population there. Among these are Tsuen Wan, Tuen Mun (Castle Peak before 1973), and Sha Tin, which were established in the 1960s and designed to have populations of between 500,000 and 700,000 each. Others, including Tai Po, Fanling, Yuen Long, and, more recently, Tseung Kwon O (Junk Bay), were designated as new towns in the 1970s, with population goals ranging from about 150,000 to 400,000. Thus, the New Territories, where only one-eighth of the population resided in 1961, accounted for more than half of the total by 2005, and some four-fifths of the New Territories population was concentrated in the new towns.

True to its original character as a fishing port, Hong Kong has a sizable, though rapidly dwindling, marine settlement. The “boat people,” or Tanka as they are locally known, are essentially fisherfolk living on junks and boats, as their ancestors did for centuries before them. They inhabit fishing towns such as Aberdeen, Shau Kei Wan, and Cheung Chau and typhoon shelters in the harbour areas. With the advance of urbanization and the decline of fishing activity, increasing numbers of them are working ashore.

True to its original character as a fishing port, Hong Kong has a sizable, though rapidly dwindling, marine settlement. The “boat people,” or Tanka as they are locally known, are essentially fisherfolk living on junks and boats, as their ancestors did for centuries before them. They inhabit fishing towns such as Aberdeen, Shau Kei Wan, and Cheung Chau and typhoon shelters in the harbour areas. With the advance of urbanization and the decline of fishing activity, increasing numbers of them are working ashore.The people

Ethnic composition (Hong Kong)

The great majority of the population is Chinese by place of origin, the non-Chinese making up only about 2 percent of the total. Non-Chinese groups are split fairly evenly between non-Asians and Asians. British, Americans, Australians, Canadians, and New Zealanders are among the non-Asians, while the Asian minority groups include Japanese, Indians, Pakistanis, and Singaporeans. An overwhelming majority of the Chinese are from Guangdong province and from Hong Kong itself, while less than 10 percent come from other parts of China, notably Fujian, Shanghai, Zhejiang, and Jiangsu, and from Taiwan.

Linguistic composition

Chinese and English are both official languages. Chinese, especially Cantonese (Cantonese language) in the spoken form, is the common language, however, and is almost universally understood. A variety of dialects and other languages are used among the ethnic minorities. Apart from Cantonese, common dialects such as Siyi, Chaochow, Hakka, Hoklo, and Tanka are popularly used within separate native communities of the Guangdong and Hong Kong Chinese. Groups from other parts of China are also likely to use their own native dialects, and, similarly, the non-Chinese are likely to use their own native languages among themselves. The use of Mandarin Chinese (Mandarin language) has risen as Hong Kong has reintegrated with China.

Religions

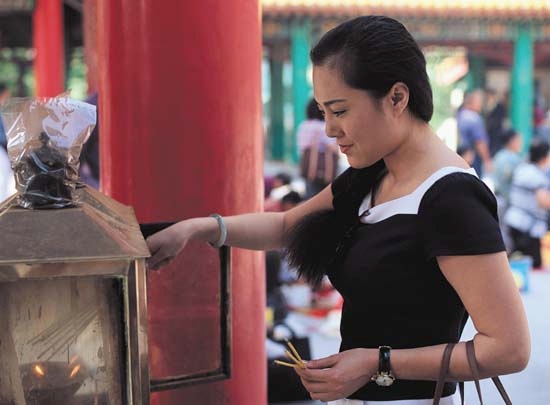

The religious persuasions of the people of Hong Kong are as various as their languages and dialects. Among the Chinese, followers of Buddhism and Daoism far outnumber other groups. The numerous Buddhist and Daoist temples and monasteries, some centuries old, play an important role in the daily life of the average Chinese. Although each temple is generally dedicated to one or two deities, it is not unusual to find images of a number of other gods or goddesses inside. For a fishing and trading port, the most significant deities are those associated with the ocean and the weather, such as Dian Hau, the goddess of heaven and protector of seafarers, who is honoured by temples at virtually every fishing harbour. Other leading deities include Guanyin (Avalokiteshvara), the Buddhist goddess of mercy; Hong Shing, god of the South Seas and a weather prophet; and Wong Daisin, a Daoist saint and deity. Some half-million people are Christians, divided roughly equally between Roman Catholics and Protestants; there are some 50 Protestant denominations and sects such as Anglican, Baptist, Lutheran, and Methodist. There are also small numbers of Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, and Jews.

The religious persuasions of the people of Hong Kong are as various as their languages and dialects. Among the Chinese, followers of Buddhism and Daoism far outnumber other groups. The numerous Buddhist and Daoist temples and monasteries, some centuries old, play an important role in the daily life of the average Chinese. Although each temple is generally dedicated to one or two deities, it is not unusual to find images of a number of other gods or goddesses inside. For a fishing and trading port, the most significant deities are those associated with the ocean and the weather, such as Dian Hau, the goddess of heaven and protector of seafarers, who is honoured by temples at virtually every fishing harbour. Other leading deities include Guanyin (Avalokiteshvara), the Buddhist goddess of mercy; Hong Shing, god of the South Seas and a weather prophet; and Wong Daisin, a Daoist saint and deity. Some half-million people are Christians, divided roughly equally between Roman Catholics and Protestants; there are some 50 Protestant denominations and sects such as Anglican, Baptist, Lutheran, and Methodist. There are also small numbers of Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, and Jews.Demographic trends

As in many large urban centres of the world, Hong Kong's population has increased in the late 20th century. Since the 1950s the average annual rate of growth has fluctuated between about 2 and 4 percent, the variations in some degree based on the sporadic flow of immigrants from China. Immigration has been a chief cause of population increase, but it was slowed through changes in immigration policy in 1980 and 1982, and emigration rose from the late 1980s. Birth rates have steadily declined since the late 1950s, the rate of natural increase falling below 1 percent by the 1980s. Life expectancy, however, has been showing a gradual increase. Since the 1950s, the proportion of the population under 15 has decreased rapidly, while that between 15 and 64 has shown a marked increase and the group over 65 has more than doubled. Hong Kong is one of the world's most densely populated places.

The economy

With its limited natural resources, Hong Kong depends on imports for virtually all of its requirements, including raw materials, food and other consumer goods, capital goods, and fuel. Under its unique status as an international free port, entrepôt trade, mainly with China, flourished until 1951, when a United Nations embargo on trade with China and North Korea drastically curtailed it. This situation, combined with the need to export and with the availability of cheap labour, led to the establishment of competitive light industries and a transformation of the economy in the early 1960s. The market economy and the laissez-faire policy of the British colonial government provided flexibility for further industrialization and the incentive and freedom, from the late 1960s, to attract foreign investment and financial transactions. In succeeding years, with China adopting a more open foreign policy, entrepôt trade rapidly revived, while Hong Kong–China trade surged. Hong Kong developed not only in manufacturing, trade, and shipping but also as a regional financial centre and as an agent in China's pursuit of modernization. The tertiary (services) sector of the economy now makes up some four-fifths of the gross domestic product (GDP).

Resources

Hong Kong is practically devoid of any significant mineral resources. The mining for graphite and lead at Cham (“Needle”) Hill and iron ore at Mount Ma On stopped long ago. The small-scale mining of feldspar, feldspar sand, and kaolin clay ceased by 1990. Hong Kong is similarly poorly endowed in other natural resources: no commercial timber is produced from its sparse forest cover, and there is no hydroelectric potential from the small and short streams. Indeed, even water has been in serious short supply as a consequence of the limited areal extent, the steep terrain, and the lack of catchment areas. In spite of the many reservoirs, which were built mostly before World War II, and several giant projects, such as the water desalinization plant at Castle Peak and the Plover Cove and the High Island reservoirs, which are enclosed sea areas, the bulk of water consumed is piped in from Guangdong province.

Agriculture and fishing

Only 6 percent of Hong Kong's land area is arable, and another 2 percent is under fishponds. Since the 1950s about one-third of the agricultural land has been lost to other uses. The growing season is year-round, however, and several crops a year are possible. Paddy rice cultivation once dominated agricultural land use, but it has practically disappeared, having been surpassed by vegetable and pond fish farming. Other minor uses include the production of fruits, flowers, and crops such as sweet potatoes, taro, yams, and sugarcane.

Marine fishing in the adjacent waters is one of Hong Kong's most important primary activities. Apart from pond fish, a marine fish culture has shown signs of development, notably in the eastern New Territories.

Industry

The rapid development of manufacturing in the 1950s was made possible by immigrant Chinese industrialists, mainly from Shanghai, who brought with them technology and capital. Foreign investments soon began to flow in to tap the huge supply of cheap labour and relatively cheap raw materials available in the surrounding region. Most of the industry has been confined to the urban areas, especially in the densely populated districts of Kowloon. With the development of industrial and other new towns, manufacturing began to disperse into Kwun Tong, Tsuen Wan, Tuen Mun, and others. In 1977 the Hong Kong Industrial Estates Corporation was established to develop and manage industrial estates that would accommodate high-technology industries, first on reclaimed land in Tai Po and later in Yuen Long.

Manufacturing, once the most important sector of the Hong Kong economy, has been overshadowed by the vast service sector; it now constitutes less than one-tenth of the gross domestic product and employs about one-tenth of the labour force. Textile and clothing production is the leading manufacturing activity and contributes about one-third of the value of domestic exports. The electronics industry is the second largest export earner. There are some heavy industries such as shipbuilding and repair and aircraft engineering. Steel rolling, production of machine parts and plastics, and cement manufacturing serve local needs. The tourist industry, which is highly promoted by the government and well catered to by the huge service sector, is another significant part of the economy. The number of tourists exceeded 10 million per year in the mid-1990s.

Finance

Since 1969 Hong Kong has emerged as one of the major financial centres of the Asia-Pacific region, despite the fact that it is without the services of a central bank. The regional government delegates the functions of such an institution to certain government offices and selected commercial banks. In addition to the licensed banks in the region, there are representative offices of foreign banks, including registered deposit-taking companies.

Domestic and international currencies are traded at the Hong Kong foreign-exchange market. The stock market attracts investment from both foreign and domestic sources. Some of its major shares are also traded on the London stock market. A gold bullion market, once the world's largest, is operated by the Chinese Gold and Silver Exchange Society. The lack of exchange controls has contributed to the success of Hong Kong as a financial centre.

Trade

Hong Kong's free-trade policy has made the territory one of the world's great centres of trade. There is no tariff on imports, except for some luxury items, such as perfumes, motor vehicles, alcoholic beverages, and tobacco. Hong Kong is dependent upon imported products, which make up about half of the total amount of external trade, the rest being divided between exports and reexports. Apart from trade with other regions of China, Japan supplies the largest percentage of imports, and other major suppliers include Taiwan, the United States, Singapore, South Korea, Germany, and the United Kingdom. Consumer goods such as clothing, radios, television sets, stereos, computers, and watches represent the largest group of imports. The second largest group includes raw materials and semi-manufactured goods such as synthetic and natural textiles, chemicals, and electronic components. Other significant imported products are machinery and transport equipment, foodstuffs, and fuels.

China became the main market for Hong Kong's products prior to 1997, and this trade remained predominant after the territory's reintegration. Other major markets include the United States, Japan, and Germany. Textiles and clothing are the leading exports. Also important are electrical machinery and appliances, office machinery, photographic apparatus, and a variety of other manufactured items. Reexports constitute a major portion of the goods shipped out of Hong Kong, which developed historically as an entrepôt port.

Transportation

With roadways limited relative to the population, the government has enforced strict limitations on automobile ownership and placed heavy emphasis on the development of public transportation. As a result, the rate of car ownership is low, although it is steadily rising. The majority of the populace makes its daily trips by public transport. Apart from the bus, tram (streetcar), and ferry, the public is also served by a unique minibus service, a rapid transit system, and an electric railway. Buses, however, are the largest carrier, responsible for more than half of the daily public transport trips excluding those by taxi, followed by the combined minibus and maxicab (a regulated form of minibus) service. The precipitous Victoria Peak area is served by one of the oldest transport companies, which operates a cable car system between the peak and the Central District.

International traffic is served by Hong Kong's international airport and its magnificent harbour, and there are good overland linkages with Guangdong province. The Hong Kong International Airport was located at Kai Tak, on the eastern fringe of Kowloon, until 1998, when it was relocated to a new, larger facility on Chek Lap Kok Island. Designed by British architect Sir Norman Foster, the airport's passenger terminal is the world's largest enclosed space, covering some 133 acres (54 hectares). The port of Hong Kong, based at one of the world's finest natural harbours, is renowned for its efficiency and capacity. The capacity of its container terminals at Kwai Chung ranks Hong Kong among the world's largest container ports. Speedy ferry service between Hong Kong and Macau and parts of Guangdong is provided by various craft, including hydrofoils and hovercraft. Railroad transportation to Guangdong is provided by the Kowloon-Guangzhou (Canton) Railway. Electrification of the railway and the growth, along its line, of the new towns of Sha Tin, Tai Po, and Fanling caused a considerable increase in passenger traffic. Externally, the line carries annually millions of tons of freight and head of livestock, as well as passenger traffic between Hong Kong and Guangdong.

International traffic is served by Hong Kong's international airport and its magnificent harbour, and there are good overland linkages with Guangdong province. The Hong Kong International Airport was located at Kai Tak, on the eastern fringe of Kowloon, until 1998, when it was relocated to a new, larger facility on Chek Lap Kok Island. Designed by British architect Sir Norman Foster, the airport's passenger terminal is the world's largest enclosed space, covering some 133 acres (54 hectares). The port of Hong Kong, based at one of the world's finest natural harbours, is renowned for its efficiency and capacity. The capacity of its container terminals at Kwai Chung ranks Hong Kong among the world's largest container ports. Speedy ferry service between Hong Kong and Macau and parts of Guangdong is provided by various craft, including hydrofoils and hovercraft. Railroad transportation to Guangdong is provided by the Kowloon-Guangzhou (Canton) Railway. Electrification of the railway and the growth, along its line, of the new towns of Sha Tin, Tai Po, and Fanling caused a considerable increase in passenger traffic. Externally, the line carries annually millions of tons of freight and head of livestock, as well as passenger traffic between Hong Kong and Guangdong.Administration and social conditions

Government

When it was a colony, Hong Kong was administered by a governor, who was appointed by and represented the monarch of the United Kingdom, directed the government, served as the commander in chief, and presided over the two main organs of government, the Executive Council and the Legislative Council. With the resumption of Chinese sovereignty over the territory in July 1997, the Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (promulgated by the National People's Congress of China in 1990) went into effect. The guiding principle of the Basic Law was the concept of “one country, two systems,” under which Hong Kong was allowed to maintain its capitalist economy and to retain a large degree of political autonomy (except in matters of foreign policy and defense) for a period of 50 years.

When it was a colony, Hong Kong was administered by a governor, who was appointed by and represented the monarch of the United Kingdom, directed the government, served as the commander in chief, and presided over the two main organs of government, the Executive Council and the Legislative Council. With the resumption of Chinese sovereignty over the territory in July 1997, the Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (promulgated by the National People's Congress of China in 1990) went into effect. The guiding principle of the Basic Law was the concept of “one country, two systems,” under which Hong Kong was allowed to maintain its capitalist economy and to retain a large degree of political autonomy (except in matters of foreign policy and defense) for a period of 50 years.The Basic Law vests executive authority in a chief executive, who is under the jurisdiction of the central government in Peking (Beijing) and serves a five-year term. Legislative authority rests with a Legislative Council, whose 60 members serve a four-year term; the chief executive, however, can dissolve the council before the end of a term. A 400-member Selection Committee was created by the central government to recommend the first chief executive and the first-term members of the Legislative Council (who are to serve for only two years).

According to the Basic Law, the chief executive for the second term was appointed by the central government, following election by an 800-member Election Committee in Hong Kong. The constituencies for council members were then defined during their second and third terms, and by the third term half were directly elected from geographic constituencies and half would be selected from “functional constituencies” drawn from business and professional circles. The Basic Law further states, however, that the chief executive and council members ultimately were to be elected by universal suffrage. These electoral procedures were to have been determined by 2007, but in that year the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress in Beijing ruled that universal suffrage would not be implemented before 2012.

Civil and criminal law is derived generally from that of the United Kingdom, and the Basic Law states that this system is to be maintained. The highest court in the judiciary is the Court of Final Appeal, headed by a chief justice. This is followed by the High Court (headed by a chief judge) and by district, magistrate, and special courts. The chief executive appoints all judges, although judges of the Court of Final Appeal and the chief judge of the High Court also must be confirmed by the Legislative Council and reported to the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress.

Education

Some three-fifths of the schools from kindergarten to secondary are private, and about another third are either subsidized or aided by public funds. The number of public schools in Hong Kong is quite small. Education is compulsory through the junior secondary level. Students finishing primary, junior secondary, and senior secondary education take examinations for allocation of school places at the next higher level.

Postsecondary schools, mostly subsidized, are strained by their small size, although efforts are being made to increase the size and number of institutions. The combined enrollment of the two universities, the University of Hong Kong (1911) and the Chinese University of Hong Kong (1963), has risen dramatically since the mid-1980s. The Hong Kong Polytechnic (1972), with mainly technical and vocational courses, and the Hong Kong Baptist University (1956), a private institution, offer degree courses in selected subjects. Colleges of education train teachers, mainly for primary schools, while responsibility for teacher training for secondary education rests with the two universities. In 1984 the City Polytechnic of Hong Kong (now the City University of Hong Kong) accepted its first students. Numerous other vocational, technical, and industrial training institutions operate throughout Hong Kong, and thousands of students are also enrolled in extension programs. Nonetheless, thousands also travel overseas each year for study. Nearly all of Hong Kong's people have at least a primary school education.

Housing

Historically, housing has been a major problem in Hong Kong, where space is limited and the number of occupants ever-growing. Changes in the residential environment between the establishment of the colony in 1842 and the Japanese occupation in 1941 were moderate, compared to those that took place in the postwar years. There was no planning in the earlier days of development, except that generally the British lived on the Peak (the area around Victoria Peak), other nationalities in the Mid-Levels (below the Peak), and the wealthy on somewhat higher ground, where the grand garden houses and large mansions remain as landmarks. Most of the Chinese lived on the lowlands surrounding the harbour, where the streets were narrow and the houses made of wood, bricks, and mortar. They lacked not only good natural lighting and ventilation but also piped water and flush toilets. Frequently urban development was the result of plagues, fires, and typhoons rather than comprehensive city planning; and the presence of large numbers of squatters and street sleepers as a result of a shortage of housing has been a persistent feature.

The limited housing supply was further reduced by the ravages of World War II. In the early postwar years, more than half of all families shared accommodations with others, living in cubicles, bed spaces, and attics and on roofs and verandas and in similar quarters. The colonial government's reluctant involvement in housing provision began with the building of resettlement blocks for fire victims in 1953, but it took real impetus in the early 1960s when the great demand for urban land resulted in the relocation of large numbers of squatters and urban poor. Eventually public housing came to accommodate more than half of the population, most of them living far from the urban core, and with growing numbers settling into the new towns. Land prices and rents have reached extremely high levels.

Health and welfare

The health of the populace is generally good, the result, in part, of an aggressive program of public measures, including the promotion of preventive medicine and personal health services, and a relatively high quality of life. Improving health indexes and a downward trend in the occurrence of major communicable diseases are leading indicators of the state of health in Hong Kong. Most deaths are caused by cancer, heart disease, and cerebrovascular diseases. Hospitals are divided into three groups: government, government-assisted, and private. These are under great pressure to meet the needs of the people. Clinics, some operated by the government, supplement other medical facilities. Boat-borne clinics provide services to some outlying villages.

The social security system is largely limited to emergency relief programs, although there are some allowances for unemployment, old age, and disabilities. The aging of the population, coupled with the extreme crowding, presents increasing problems of elderly care. Spending on social welfare increased significantly in the mid-1990s.

Cultural life

Cultural milieu and the arts

Hong Kong's is truly a mixed culture. Not only does the territory celebrate festivals and holidays of the East and the West, such as the Dragon Boat Festival, the Mid-Autumn Festival, the Lunar (Chinese) New Year, Christmas, the Western New Year, and others, but it also enjoys hundreds of annual cultural events ranging from traditional Cantonese and other Chinese regional operas and puppet shows to performances of ballet, theatre, and music and exhibitions of paintings and sculptures by nationally and internationally renowned performers and artists. The Hong Kong Arts Festival has become one of Asia's major cultural events, and the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra, the Hong Kong Chinese Orchestra, the Chung Ying Theatre Company, and the City Contemporary Dance Company are among the best-known local artistic groups. The Hong Kong Conservatory of Music and the Hong Kong Academy of Ballet have been combined into the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts, offering full-time diploma courses in dance, drama, music, and technical arts.

Scores of motion pictures are produced every year in Hong Kong, many of which attain international fame; some have even started new trends in the art, such as the so-called kung fu films. The Hong Kong International Film Festival, inaugurated in 1977, is a major event, especially for the display of Asian films. Hong Kong is also a regional as well as an international centre in fashion design and in the cutting and design of ornamental diamonds.

Cultural institutions

Apart from the libraries of the major educational institutions, Hong Kong has a system of 25 libraries, including mobile ones. Of the museums, major ones include those specializing in history, art, science and technology, and space. The multifunctional City Hall (a cultural centre) and the Art Centre provide the major gallery, theatrical, and concert facilities. In addition, town halls have been established in the new towns and cultural centres in some districts to serve local communities.

Recreation

Hong Kong's country park system covers two-fifths of the land area, and outdoor recreation in parks is a part of the way of life for many of the people. City dwellers use park areas on the urban fringe for walking, running, and tai chi chuan, among other activities, while remoter locations are used for kite flying, picnicking, hiking, cycling, and camping. There are well-organized programs of recreation and sports at the community level. The Ocean Park, one of the world's largest oceanariums, the Hong Kong Coliseum, a 12,500-seat indoor stadium that is among the largest in Asia, and the Queen Elizabeth Stadium are among the best venues for local and international sports events and musical, cultural, and entertainment programs. For those who can afford it, the many inlets and bays in Hong Kong provide a superb setting for pleasure sailing, waterskiing, canoeing, and other aquatic sports; the Hong Kong Yacht Club is one of the most active in the South China Sea region.

Hong Kong's country park system covers two-fifths of the land area, and outdoor recreation in parks is a part of the way of life for many of the people. City dwellers use park areas on the urban fringe for walking, running, and tai chi chuan, among other activities, while remoter locations are used for kite flying, picnicking, hiking, cycling, and camping. There are well-organized programs of recreation and sports at the community level. The Ocean Park, one of the world's largest oceanariums, the Hong Kong Coliseum, a 12,500-seat indoor stadium that is among the largest in Asia, and the Queen Elizabeth Stadium are among the best venues for local and international sports events and musical, cultural, and entertainment programs. For those who can afford it, the many inlets and bays in Hong Kong provide a superb setting for pleasure sailing, waterskiing, canoeing, and other aquatic sports; the Hong Kong Yacht Club is one of the most active in the South China Sea region.Press and broadcasting

A wide-ranging and sophisticated communications network has developed in Hong Kong, reflecting its thriving commerce and international importance. There are some 60 newspapers (in various languages, but mostly Chinese) and the numbers of periodicals run into the hundreds. The territory is in addition the East and Southeast Asian headquarters for most of the major international news services. Broadcast news is provided by several television and radio companies, one of which is government-run. Under the British administration, the press developed largely free from government censorship. Television provides the major source of news and entertainment for the average family, and the Chinese television programs produced are not only for local consumption but also for overseas markets. Hong Kong also ranks as an important centre of publishing and printing: numerous books are published yearly for local consumption, several leading foreign publishers have their regional offices in Hong Kong, and many international magazines are printed in the territory.

History (Hong Kong)

Early settlement

Archaeological remains of pottery, stone implements, rings, and bronzes found on more than 20 sites are evidence of settlements in Neolithic times. The earliest modern peoples in Hong Kong are thought to have come from North China in the 2nd millennium BCE. The Cantonese began to settle in the area about 100 BCE; later came the Hakka, and by the mid-17th century the Hoklo had arrived. Hong Kong was the scene of the last struggles between the declining Ming dynasty and the rising Ch'ing, led by the Manchus.

Before the British arrived in the mid-19th century, Hong Kong Island was inhabited only by a small fishing population, with few features to recommend it for settlement. It lacked fertile soil and fresh water, was mountainous, and was reputed to be a notorious haunt of pirates. But it was a relatively safe and undisturbed base for the British merchants who in 1821 began to use the fine harbour to anchor opium-carrying vessels. The great commercial and strategic significance of this deep, sheltered harbour, possessing east and west entrances and lying on the main trade routes of the Far East, was quickly realized.

After the first Opium War (Opium Wars) (1839–42), Hong Kong Island was ceded to Britain by the Treaty of Nanjing. The British were never satisfied with an incomplete control of the harbour, however. Less than 20 years later, after the second Opium War (1856–60), China was forced to cede the Kowloon Peninsula south of what is now Boundary Street and Stonecutters Island by the Convention of Beijing (1860). By the Convention of 1898, the New Territories together with 235 islands were leased to Britain for 99 years from July 1, 1898. With this expansion of territory, Hong Kong's population leaped to 120,000 in 1861 and to more than 300,000 by the end of the century.

Events before and during World War II

Almost since its establishment, Hong Kong, more than any other treaty port, afforded a refuge for runaway persons and capital from China as well as an interim abode for rural emigrants destined for Southeast Asia and beyond. Such movements of Chinese people between China and Hong Kong were free and were highly responsive to the political and economic conditions in China. After the establishment of the Republic of China in 1912, proponents of emerging nationalism sought to abolish all foreign treaty privileges in China. A boycott against foreign goods particularly hurt Britain, which was well established in China. The campaign soon spread to Hong Kong, where strikes in the 1920s caused agitation.

Almost since its establishment, Hong Kong, more than any other treaty port, afforded a refuge for runaway persons and capital from China as well as an interim abode for rural emigrants destined for Southeast Asia and beyond. Such movements of Chinese people between China and Hong Kong were free and were highly responsive to the political and economic conditions in China. After the establishment of the Republic of China in 1912, proponents of emerging nationalism sought to abolish all foreign treaty privileges in China. A boycott against foreign goods particularly hurt Britain, which was well established in China. The campaign soon spread to Hong Kong, where strikes in the 1920s caused agitation.When the Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1937, Hong Kong was once more a refuge, with thousands of Chinese fleeing to it before the advancing Japanese. With the outbreak of war (World War II) in Europe in 1939, the position of the colony became even more precarious, and the Japanese attacked and occupied Hong Kong in December 1941. During the war years Hong Kong's commerce was drastically impaired; food was scarce, and many residents fled to inland China. The population, which had numbered 1,600,000 in 1941, was reduced to about 650,000 by 1945 when the Japanese surrendered.

Modern Hong Kong

British troops returned to the city on Aug. 30, 1945, and civil government was reestablished in May 1946. Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of Chinese and foreigners returned, and they were soon joined by economic and political refugees from China, who were fleeing the civil war between the Nationalist and communist armies.

The United Nations embargo in 1951 on trade with China and North Korea during the Korean War seriously curtailed the entrepôt trade, the lifeline of the colony, and for several years conditions were depressed. Hong Kong began its revival based on light industries such as textiles, which were set up by immigrant capitalists and provided needed employment. These soon assumed their importance in the economy, providing as well the basis for further industrialization. But it was because much of the development depended on cheap labour, which toiled under extremely poor working conditions, that labour disputes and social discontent began to spread in the early 1960s. Severe riots broke out in Hong Kong and Kowloon in May 1967 following a labour dispute in a plastic-flower factory. The economic and social unrest was immediately turned into violent political demonstrations, largely inspired by followers of the Cultural Revolution (1966–76) in China. When the situation stabilized toward the end of the 1960s, general working and living conditions were notably improved by labour legislation, large government housing projects, and extensive public works programs. Simultaneously, high-technology industries such as electronics were developed, and the property and financial markets prospered until early 1973, when the stock market collapsed as billions of dollars were drained out of Hong Kong. From the mid-1970s the economy resumed its upward trend as relations with China improved.

In the late 1970s, concern about the future of Hong Kong began to loom large, as British jurisdiction over the leased areas of the New Territories neared the 1997 expiration date. Although the lease applied only to the New Territories, the Chinese government had consistently maintained that the whole of Hong Kong was Chinese territory and considered that the question of the earlier Hong Kong–British agreements came under the category of unequal treaties and also required resolution. Initial contacts between the two governments on the matter were made from March 1979, but formal negotiations did not start until after the visit of the British prime minister to Beijing in September 1982. Negotiations continued for two years. Finally, the Chinese-British joint declaration on the question of Hong Kong was formally signed by the heads of the two governments in Beijing on Dec. 19, 1984. The agreement stipulated that Hong Kong (including Hong Kong Island, Kowloon, and the New Territories) would be recovered by China from July 1, 1997. There ensued a period of often difficult negotiations between Hong Kong and Beijing on the final wording of the document by which Hong Kong would be governed under Chinese sovereignty. Despite some reservations from Hong Kong, the National People's Congress formally ratified the Basic Law on April 4, 1990, which took effect on July 1, 1997, and established the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region directly under the central government.

Meanwhile, Hong Kong's economy experienced steady growth, despite its heavy dependence on global economic conditions. The already significant economic ties with the mainland increased even more dramatically after reunification. In addition, major resources were devoted to improving the region's transportation infrastructure, which included new bridges and roadways in addition to the new airport. Hong Kong was hit hard by an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome ( SARS) in 2003, which killed some 300 people there and 350 more on the mainland and, for a time, significantly reduced tourism in the region. However, the crisis soon passed. Hong Kong played host to the equestrian events of the 2008 Olympic Games.

Meanwhile, Hong Kong's economy experienced steady growth, despite its heavy dependence on global economic conditions. The already significant economic ties with the mainland increased even more dramatically after reunification. In addition, major resources were devoted to improving the region's transportation infrastructure, which included new bridges and roadways in addition to the new airport. Hong Kong was hit hard by an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome ( SARS) in 2003, which killed some 300 people there and 350 more on the mainland and, for a time, significantly reduced tourism in the region. However, the crisis soon passed. Hong Kong played host to the equestrian events of the 2008 Olympic Games.Additional Reading

General works

A well-illustrated discussion of geography, history, economy, and society is presented in Hong Kong (annual), issued by the Hong Kong Government Information Service. David Fu-Keung Ip, Chi-Keung Leung, and Chung-Tong Wu (comps.), Hong Kong: A Social Sciences Bibliography (1974); Alan Birch, Y.C. Jao, and Elizabeth Sinn (eds.), Research Materials for Hong Kong Studies (1984); and Ian Scott (compiler), Hong Kong (1990), are useful for further research on all aspects of Hong Kong.

Physical and human geography

Geologic studies of Hong Kong include P.M. Allen and E.A. Stephens, Report on the Geological Survey of Hong Kong, 1967–1969 (1971); and Bryan P. Ruxton, “The Geology of Hong Kong,” Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London, 115:233–260 (1960). An analysis of the political, economic, geographic, and social developments in Hong Kong up to the early 1980s is found in Chi-Keung Leung, J.W. Cushman, and Wang Gungwu (eds.), Hong Kong: Dilemmas of Growth (1980). Frank Leeming, Street Studies in Hong Kong: Localities in a Chinese City (1977), examines Hong Kong's neighbourhoods. Socioeconomic studies include Hong Kong Social and Economic Trends, 1970–1980 (1981), compiled by the Hong Kong Census and Statistics Department; A.J. Youngson, Hong Kong, Economic Growth and Policy (1982); Sek Hong Ng and David A. Levin, Contemporary Issues in Hong Kong Labour Relations (1983); E.F. Szczepanik, The Economic Growth of Hong Kong (1958, reprinted 1986); William F. Beazer, The Commercial Future of Hong Kong (1978); and Thomas R. Tregear, A Survey of Land Use in Hong Kong and the New Territories (1958). Hong Kong in Search of a Future (1984), ed. by Joseph Y.S. Cheng; Peter Harris, Hong Kong: A Study in Bureaucratic Politics (1978); Siu-Kai Lau (Chao-Chia Liu), Society and Politics in Hong Kong (1982); and Norman Miners, The Government and Politics of Hong Kong, 5th ed. updated (1995), address the politics of the territory.

History

Overviews are provided by Jan Morris, Hong Kong (1988); Nigel Cameron, An Illustrated History of Hong Kong (1991); Frank Welsh, A Borrowed Place: The History of Hong Kong (1993); and Ming K. Chan and John D. Young (eds.), Precarious Balance: Hong Kong Between China and Britain, 1842–1992 (1994). Jung-Fang Tsai, Hong Kong in Chinese History: Community and Social Unrest in the British Colony, 1842–1913 (1993), focuses on the Chinese elite and working classes in Hong Kong from the end of the First Opium War to the beginning of the republican period in China. Norman Miners, Hong Kong Under Imperial Rule, 1912–1941 (1987), addresses the political and economic issues of the period before the Japanese occupation.Aspects of the transition from British to Chinese rule are explored in Gerard A. Postiglione (ed.), Education and Society in Hong Kong: Toward One Country and Two Systems (1991), on the important role of the educational system; Gerald Segal, The Fate of Hong Kong (1993), an overview; Enbao Wang, Hong Kong, 1997: The Politics of Transition (1995), an optimistic outlook; Bruce Bueno De Mesquita, David Newman, and Alvin Rabushka, Red Flag Over Hong Kong (1996), a more pessimistic forecast; and Steve Shipp, Hong Kong, China: A Political History of the British Crown Colony's Transfer to Chinese Rule (1995), which includes the complete texts of, among others, the 1984 Joint Declaration and the Basic Law. Ed.

- Chattanooga, Battle of

- Chatterjee, Bankim Chandra

- chatter mark

- Chatterton, Thomas

- chat-thrush

- Chatti

- Chattian Stage

- Chatwin, Bruce

- Chaucer, Geoffrey

- Chaudor carpet

- Chauk

- Chauliac, Guy de

- Chaumette, Pierre-Gaspard

- Chaumont

- Chauncey Jerome

- Chauncey Mitchell Depew

- Chauncy, Charles

- Chausson, Ernest

- Chautauqua

- chautauqua movement

- Chautemps, Camille

- chauth

- Chauvelin Family

- chauvinism

- Chauvin, Yves